How scientists made this 95 million-year-old octopus look good

The magnificently preserved fossil was not immediately so distinct. See how a fossil can be prepared for display.

Nearly a hundred million years ago something special happened to this octopus.

“We don’t know exactly how this got to be so well preserved but the conditions for it must have been terrific,” says Palaeontologist Jørn Hurum. He is a professor at the University of Oslo’s Natural History Museum and we are looking at a special fossil in the museum’s collections.

This octopus was found in a Lebanese quarry.

Jørn Hurum explains that it might have drifted into a salt lagoon after it died. Such lagoons consist of seawater that has been cut off from the rest of the ocean. The salinity of this dammed up water increases as surface water evaporates. It can become so salty that most bacteria and microorganisms cannot survive there.

“So there is nothing to decompose the octopus,” says Hurum.

If an animal is simultaneously covered by a fine-grained silt and sand, even imprints and signs of its soft tissue can be preserved. Even the ink in its ink sac has tinged the rock that reveals how the octopus looked nearly 100 million years ago.

However, this fabulous specimen in sedimentary stone did not look this good when it was discovered.

Preparations

First the fossil had to be reassembled, cleaned and dolled up.

An expert from Germany, Mike Bätjer, has put the rock pieces of the octopus together and photographed the steps he took in the process of turning it into a showcase specimen.

(Photo: Mike Bätjer)

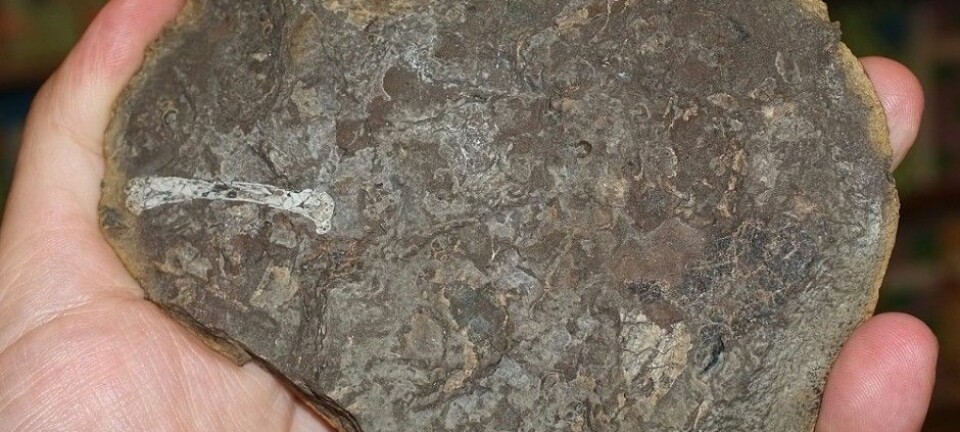

“This is the way it looked when found,” says Hurum. He explains that the fossil was unusually complete and the person who found it managed to include lots of small pieces.”

This enabled the fossil to be very whole when assembled by Bätjer.

(Photo: Mike Bätjer)

“Here has started to put the pieces together. It requires training to see how these pieces actually fit,” explains Hurum.

(Photo: Mike Bätjer)

All the pieces are in place. This photo shows how the tentacles end on one piece and continue on another. The corresponding piece of rock had broken off but the person who brought it out of the quarry managed to include everything. Bits of rock are meticulously removed to reveal the tentacles and the pieces are conjoined using super glue.

(Photo: Mike Bätjer)

The tentacles embedded in the rock are revealed and sections of rock are glued together.

(Photo: Mike Bätjer)

“He uses a tiny vibrating needle which cuts away on the rock. He uses a microscope to follow the progress of this as he works,”

Hurum calculates that Bätjer’s job of freeing the rock layer covering some of the tentacles took about a week.

(Photo: Mike Bätjer)

Another piece is glued on. A part of the tentacles is reattached.

“Then the pieces are held tightly together with a clamp. The glued seam is nearly invisible.”

The piece is glued on and the tentacles hidden in the rock need to be revealed again. A small ridge occurs where the rock piece is glued on.

(Photo: Mike Bätjer)

Then the pieces are conjoined with epoxy glue. The glue has been coloured with paint.

“Although the colour looks too light, the mixture is made to camouflage the cracks once the glue has dried and been polished. A lot of experience is needed to create the right colour,” says Hurum.

(Photo: Mike Bätjer)

“A coat of stabilizing varnish is applied to the rock because it is rather soft.”

(Photo: Mike Bätjer)

“Now the job is nearly done. The cracks in the rock are touched up with coloured adhesive to conceal them,” says Hurum.

This series of photos was made to document that the fossil is not artificially enhanced or faked.

“Even though he has touched up the rock matrix, the fossil part is untouched. The documentation of this is one of the reasons why he took this series of photos.”

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling