An article from Expertanswer Sweden

Political drama in occupied Denmark

When German occupants met Danish nazis after the occupation of Denmark in WW2, there was little harmony, but political opposition.

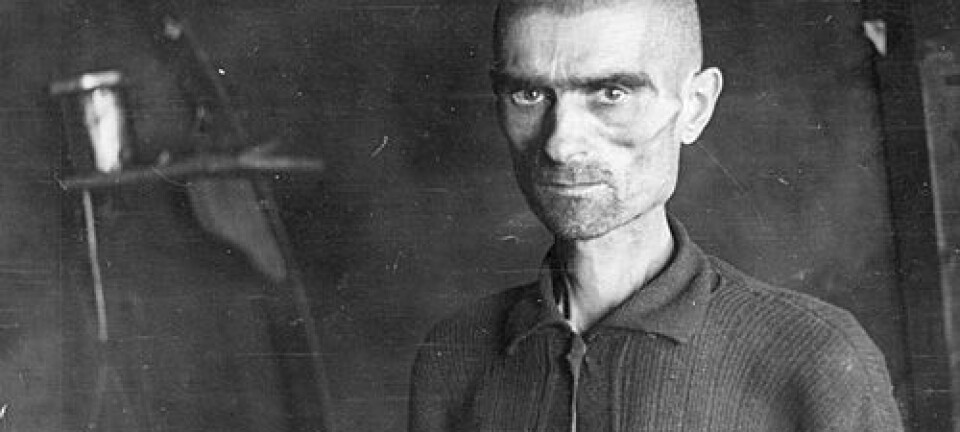

Steffen Werther at Södertörn University in Sweden has studied how the SS’s Greater Germanic ideology was received by two competing national socialist parties in southern Denmark during World War II. What actually happened when SS entered the political picture?

Germany’s occupation of Denmark was the starting shot for a political drama involving three national socialistic camps.

In North Schleswig/Southern Jutland there were already two Nazi parties: the Danish-oriented Denmark’s National Socialistic Labor Party (DNSAP) and the party of the minority Germans, the National Socialistic German Labor Party – North Schleswig (NSDAP-N).

One race, one realm

The Greater Germanic ideology that the SS embraced was based on the notion of a commonality based on race. They claimed that there was a Nordic-Germanic race and that it would be united in one realm, regardless of whatever nationalities might be involved.

This flew in the face of the two parties’ different viewpoints.

The Danish Nazis in the DNSAP primarily wanted to defend the Danish people, fearing that they would lose their national independence if they were subsumed under a Greater Germanic realm.

“They suspected that the Greater Germanic ideology might be poorly disguised imperialism. They envisioned Denmark becoming a tiny province in a Germanic realm governed by Germany,” says Steffen Werther, who recently completed his PhD in history.

The minority Germans in the NSDAP-N were also opposed to the Greater Germanic ideology. This was because the SS made the mistake of categorizing the minority Germans as Danes, or as part of the “Nordic race.”

“This was a direct insult to the minority Germans in the NSDAP-N, who saw themselves first and foremost as Germans. They didn’t want to be part of some Greater Germanic community that included other nationalities,” explains Steffen Werther.

“Instead, they wanted the borders from 1920 to be redrawn, so that North Schleswig would belong to Germany,” says Steffen Werther.

Reluctant collaboration

Both parties were thus in dire circumstances after the occupation. They didn’t want to give up their nationalist ways of thinking, but owing to the tremendous power imbalance, they couldn’t wiggle out of SS demands and claims.

The parties tried to accommodate the SS by cherry picking among arguments from the folk-national and racially Greater Germanic repertoire to fit their own political goals. But their collaboration was always marked by extreme unwillingness.

“The basic conflict between the national socialistic community concepts of ‘race’ and ‘folk’ was never resolved. Neither of the parties was willing to accept any solution proposed by the other,” says Steffen Werther.