An article from Norwegian SciTech News at SINTEF

Creating plastics packaging out of wood

A wood fibre only 100 nanometres thick might give us tomorrow’s plastic food packaging.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

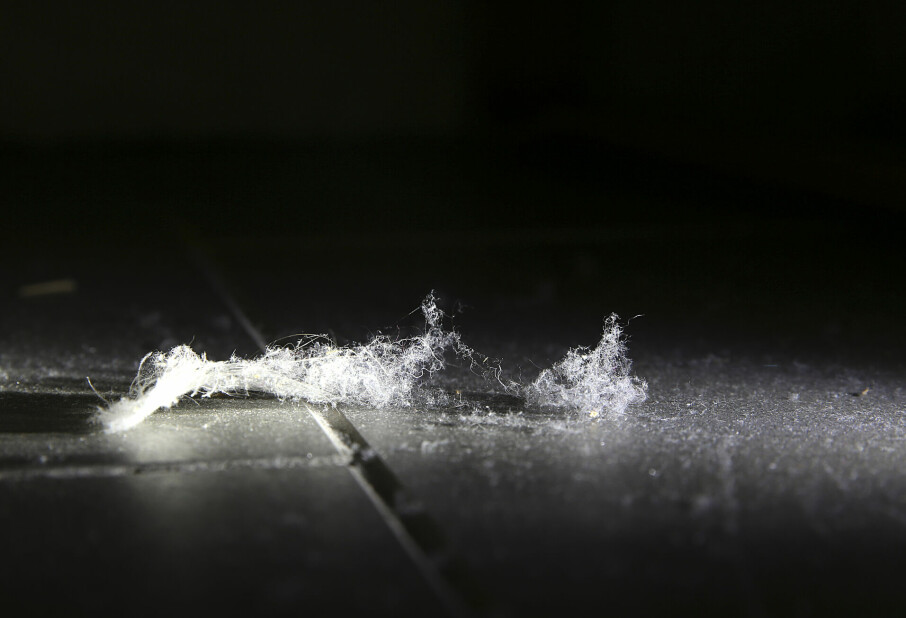

Cellulose can be broken down into what is called microfibrillated cellulose (MFC).

MFC consists of plant fibres that are only 100 nanometres in diameter, but can be extremely long, making them highly suitable as a reinforcement material for biodegradable plastics.

MFC membranes have also been shown to be impermeable to gases such as oxygen and can therefore be used to protect foodstuffs.

Climate-friendly alternative

Most of today’s plastics are petroleum-based, but scientists are now trying to create a climate-friendly alternative to plastics from renewable resources - bioplastic and MFC.

“Bioplastics can make a contribution to sustainable development," says the project manager, senior scientist Åge Larsen of Norwegian research institute SINTEF. "Our aim is to develop materials and packaging that will add as little as possible to our environmental footprint, and ideally, will be climate-neutral. In any case, as the oil runs down we are going to need alternative raw materials”

Larsen finds that gaining political understanding for climate mitigation measures is heavy going.

“But if we can demonstrate that there are good alternatives to petroleum-based products, I can imagine that this could help bring in such measures a bit faster,” says Larsen.

But couldn’t recycling plastic do such the same thing?

“Recycling is useful, but in practice, recycled plastics often end up a step or two futher down the quality ladder than the original raw material," says Larsen. "This is why we believe that MFC fibrils in combination with bioplastics will help us produce high-quality, environment-friendly packaging in the form of products such as bottles, jars and plastic foil.”

Food that keeps better

SINTEF has previously worked on barrier properties of food packaging, making use of nanotechnology to improve the shelf life of foods by limiting their exposure to oxygen. This experience will benefit the new project, which includes no fewer than 15 Norwegian and foreign participants from the industry and the university sectors.

The background of the project is that the EU has an ambition to make the people of Europe healthier by offering them more fish and seafood. Packaging that prolongs the shelf life of food can help persuade more consumers to choose healthier alternatives and at the same time reduce food waste. Borregaard is one of the main suppliers involved in the project, as the company produces the fibrils that will make bioplastic impermeable to oxygen.

Hans Henrik Øvrebø is in charge of technology development at Borregaard, and he is convinced that microfibrillated cellulose is a promising raw material.

“Borregaard is putting a lot of R&D effort into applications of microfibrillated cellulose. Participation in this project will give us valuable insight into the properties of this special type of plant fibre, and how it can be used in plastic products that are impermeable to gases," says Øvrebø.

"We think that in the long run, MFC could be used in several of our new products. We are currently in the process of reconfiguring one of our pilot plants to produce this type of cellulose.”

The first phase of the project will look at methods and a range of possibilities. Work on the first prototype is expected to get under way in a couple of years.