Tax havens can drive environmental degradation

A new study from Sweden shows how the use of tax havens is indirectly linked to illegal fishing as well as deforestation in the Amazon.

We all know that rainforests are disappearing at an alarming rate as developers cut them down to grow soybeans and to farm cattle. But where does the money come from to finance this activity?

A new study shows that 68 per cent of the funds that financed these industries between 2000 and 2011 came from tax havens. Researchers also found that 70 per cent of vessels known to be involved in illegal fishing are or have been registered in countries that are considered tax havens.

“Our analysis shows that the use of tax havens is not only a socio-political and economic challenge, but also an environmental one. However, financial secrecy hampers the ability to analyse how financial flows affect economic activities on the ground, and their environmental impacts,” says Victor Galaz, first author of the study, in a press release from Stockholm University.

The secrecy that surrounds financial activity in tax havens makes studying these links extremely challenging, the researchers said.

"This research is one of the hardest things we have done. The biggest challenge is getting good data. The other challenge is that as researchers, we’re entering a whole new world,” says Henrik Österblom, one of the authors of the study.

The researchers said that if the global community is going to work together to protect and conserve the environment, it must address the role that tax havens play in destroying the planet’s natural resources.

“This lack of transparency hides how tax havens can play a key role in facilitating the degradation of environmental commons that are crucial for both people and planet at global scales,” the researchers said in the press release.

“The Amazon rainforest, for example, is critical for stabilizing the Earth’s climate system while the ocean provides a vital source of protein and income for many millions of people worldwide, particularly in low-income food-deficit countries.”

155 billion for soy and meat

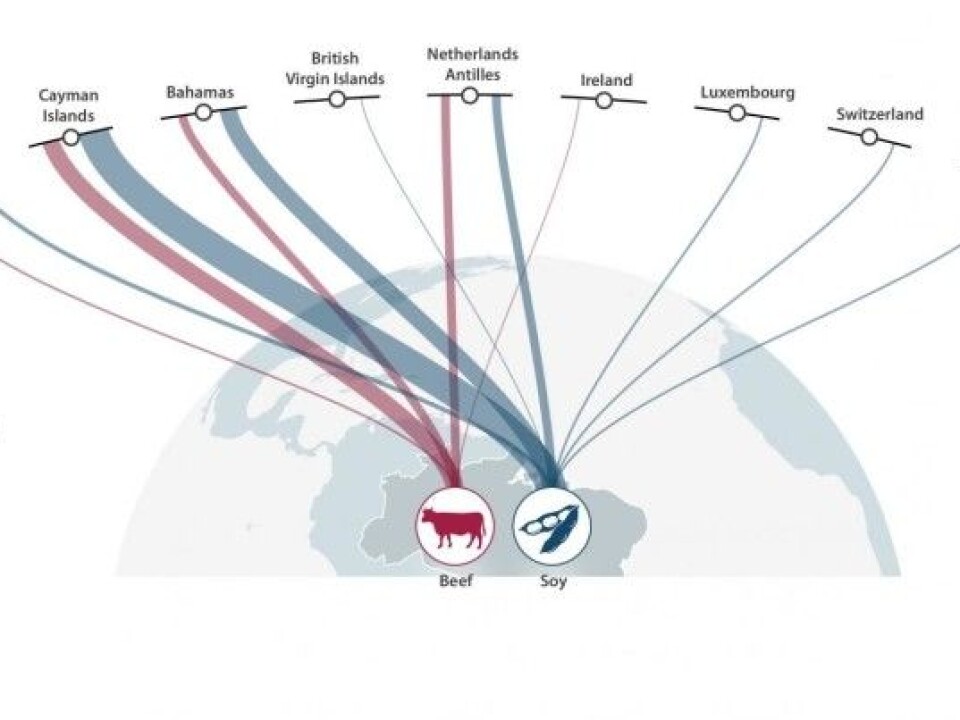

The researchers got access to data from the Brazilian central bank, including a record of money transfers from 2000 to 2011. This allowed them to calculate how much money went from tax havens to two big industries that are associated with deforestation in the Amazon.

They found that nine companies involved in the production of soy, beef and veal received NOK 155 billion, or roughly EUR 16 billion, in transfers from tax havens. This represented 68 per cent of all foreign capital that was invested in the nine companies. Most of the transfers came from the Cayman Islands and the Bahamas.

"What we can say is that there are links between money from tax havens and companies that operate in the Amazon in the meat or soy industry. On the other hand, we cannot directly say that any of these companies are engaged in illegal activities or directly affect the environment,” says Österblom.

Shady investments

Anne Leifsdatter Grønlund from the Rainforest Foundation Norway says that the study is important.

“It’s very difficult to get an overview of the effects of cattle farming in Brazil, and it’s impossible to be certain that the beef that eventually ends up in the supermarket has not contributed to deforestation,” she said. “This kind of deforestation doesn’t happen in big swaths, but in smaller areas that are cut so cattle can graze. When the fodder in that area is all gone, another area is cut for grazing and so on. Afterwards, the areas can be used to grow soy, for example.”

Leifsdatter Grønlund says the use of tax havens to fund these businesses is a problem because it makes it harder to target the sources.

“Using tax havens avoids visibility and publicity. Openness is key for stopping environmental crimes,” she said.

Fishing under another flag

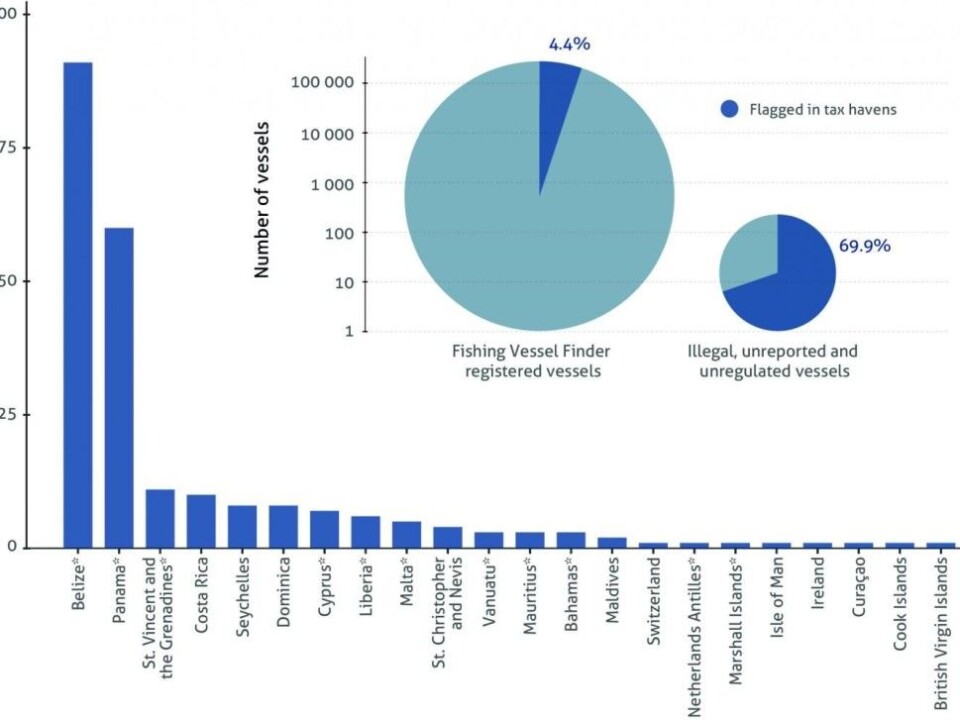

Researchers also investigated the connection between tax havens and illegal fishing. They combed through several databases, including the Fishing Vessel Finder and data from Interpol. They found that 70 per cent of ships involved in illegal and unregistered fishing either are or have been registered in tax haven countries.

Ship owners can pay to sail under what are called flags of convenience. The ship is registered in the tax haven country, which allows ship owners to evade taxes and fees in their home country.

Many of the states that offer flags of convenience have limited ability to monitor and punish fishing vessels that break the law, making it easier for vessel owners to ignore international agreements and laws.

Overfishing is a serious problem, with an estimated 30 per cent of large commercial fisheries considered overexploited, and between 11 and 26 million tonnes of illegal or unreported catches estimated to be fished worldwide, the researchers wrote in their article, published in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

“Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing is repeatedly identified by the UN General Assembly as ‘one of the greatest threats to fish stocks and marine ecosystems’,” they said.

“The global system of fishing value chains, complex ownership structures and limited management capacity in many coastal nations, make the sector vulnerable to tax havens," says Österblom.

The researchers said that the loss of tax revenues that result from the use of tax havens should be considered indirect subsidies for activities that harm the environment.

"Setting tax havens on the global sustainability agenda is important for protecting the environment and achieving the UN's sustainable development goals," the researchers wrote.

The study was a collaboration between the Stockholm Resilience Centre, an international research initiative of Stockholm University and the Beijer Institute of Ecological Economics at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, and the Global Economic Dynamics and the Biosphere programme (GEDB), based at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no.