Ancient skeletons are a bit like puzzles

It can take many years to put them together. And scientists can make mistakes putting the pieces together, too.

The Natural History Museum in Oslo has a life-sized copy of a Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton.

His name is Stan, and he’s very popular with visitors.

Stan is about 65 million years old. His skeleton is among the best preserved dinosaur skeletons in the world. About 70 per cent of the original skeleton is completely real.

The people who excavated Stan were incredibly lucky. They had a pretty easy job putting his pieces together into a complete skeleton.

But it’s not always that straight forward.

We want to see a flying lizard!

The body of a flying lizard that lived more than 100 million years ago, during the time of the dinosaurs, was as big as a grown man. Its wingspan, from one wingtip to the other, was seven metres long.

Petter Bøckman works at the Natural History Museum. He is a zoologist and university lecturer. He told us more about the flying lizard.

We at sciencenorway.no became curious. Is there any chance there will be a real flying lizard skeleton at the museum anytime soon?

Have a flying lizard - but ...

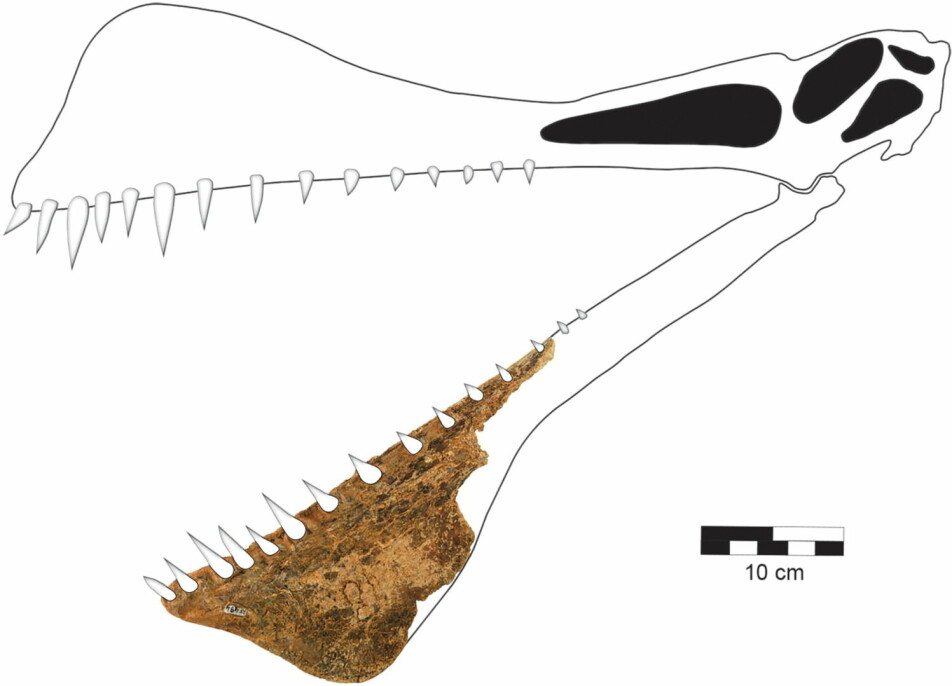

“We actually have one flying lizard, but only a bit of a wing from a fairly small animal,” Bøckman says.

Now he and his colleagues are preparing a new exhibition. They have not gotten their hands on a huge flying lizard yet.

“Of course we dream of getting a big flying lizard one day!” Bøckman said.

The problem is that there are not that many of them. These fossils are very rare and hard to find.

Eaten or rotted away

“It takes very special conditions for an animal that lives in the air to become a fossil. It has to fall down in the right place at the right time,” Bøckman said.

Stan was petrified, in a way. After he died, a flood came. He was covered with sand and clay.

Flying lizards lived along the coast. When they died, they mostly fell into the sea and were eaten up. Otherwise, they fell on beaches and boulders and were crushed by the waves.

Flying animals also have thinner bones. These lightweight bones can’t handle such rough treatment, Bøckman said.

A kind of puzzle

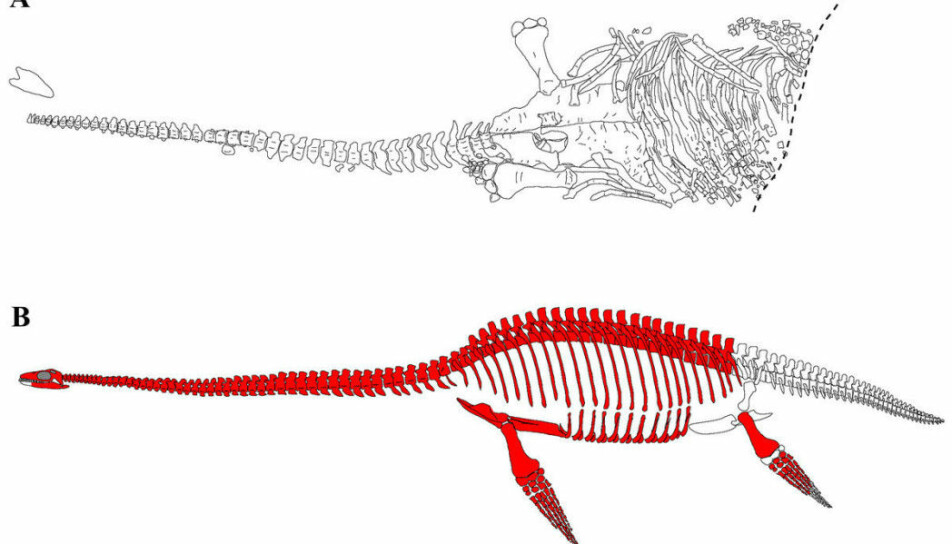

It’s most common for geologists to find skeletons that are missing lots of pieces, and rare for them to find one that is mostly whole, like Stan.

They found only a small piece of the flying lizard. It was part of the lower jaw.

Nevertheless, scientists are able to figure out what an animal looked like in many situations like this.

How can they do that? They only have a little piece!

Bøckman explains.

Sometimes another part from the same species is in a drawer in a museum. Or a part from another species that is very similar. It can be a bit like a jigsaw puzzle that way. It’s a puzzle that can take many years to complete.

When it comes to figuring out how the animal lived, the approach is a bit the same. The researchers look at animals that are similar.

What do similar animals do?

“If several relatives look the same or do the same thing, we can usually assume it applies to the species we’re studying as well,” Bøckman says.

Crocodiles are relatives of dinosaurs, and they make nests. Birds are the descendants of dinosaurs, and they make nests.

So the researchers figured that dinosaurs also built nests. This turned out to be true, since scientists have gradually found dinosaur nests.

Scientists can also be wrong

But they have also made mistakes sometimes.

Scientists know, for example, that most carnivorous dinosaurs walked on two legs. So when scientists found the fish-eating predatory dinosaur Spinosaurus, they figured it did the same thing.

“Unlike all other predatory dinosaurs, they seem to have walked on all fours,” says Bøckman. That’s in contrast to the first reconstructions.

Some species have evolved in an unexpected way. So these puzzles still can surprise scientists, Bøckman said.

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no