Researchers' Zone:

How can we save dissidents from persecution?

Public intellectuals are on a global scale being terrorized by those in power. A Danish project examines their conditions and methods to help them.

Umud is a journalist from a country in the Middle East. He is living in exile in Denmark and is persecuted by the government in his home country because they do not appreciate that he exposes the widespread violence, corruption, and oppression.

During an art festival in Finland, he and I talk casually, and we agree to meet the next day. Umud wishes the interview to take place in a large cafe in Helsinki’s inner city, because both for mine and his own safety's sake, it should be in a public area surrounded by many people.

When I ask him to explain his motives for fleeing, I am not prepared for the disheartening narratives.

After a long gaze into his cup of tea, he looks at me with a resigned look. During the last two months alone, eight of his colleagues have 'disappeared', he reveals. Umud and several of the other participants in the project say 'to disappear' when individuals are unofficially executed, either by the government, religious groups or organized crime.

A focus on intellectuals in Nordic exile

Like Umud, public intellectuals (see definition of intellectuals) such as journalists, researchers, artists and writers are persecuted in their home countries. In a research project, I and other researchers examine their economic, social and professional conditions and current needs, as well as how countries like the Nordics can help them.

We wish to develop methods to better support these individuals, and our findings show that among other factors it is done by refining the already existing initiatives in the host countries.

In addition, the project seeks to provide insight into the participants’ imaginings of the future, and why they continue the struggle for human rights and freedom of speech.

Geographically, they come from a number of countries in the Middle East, Africa, South America, Asia and Eastern Europe, and we focus on communities and individuals in Denmark, Sweden, Finland and Norway.

Our data collection uses observation, interviews and analysis of political documents, and the project takes place in collaboration with civil society, the public sector, educational institutions, free cities and community centres.

Billions live under oppressive governments

The intellectuals are critical of the governments in their home countries and they risk persecution, often with their life at stake. Regrettably, such experiences are part of everyday life for a growing number of people, as research shows that people living under oppressive governments now make up a majority, comprising 54 percent of the world's population.

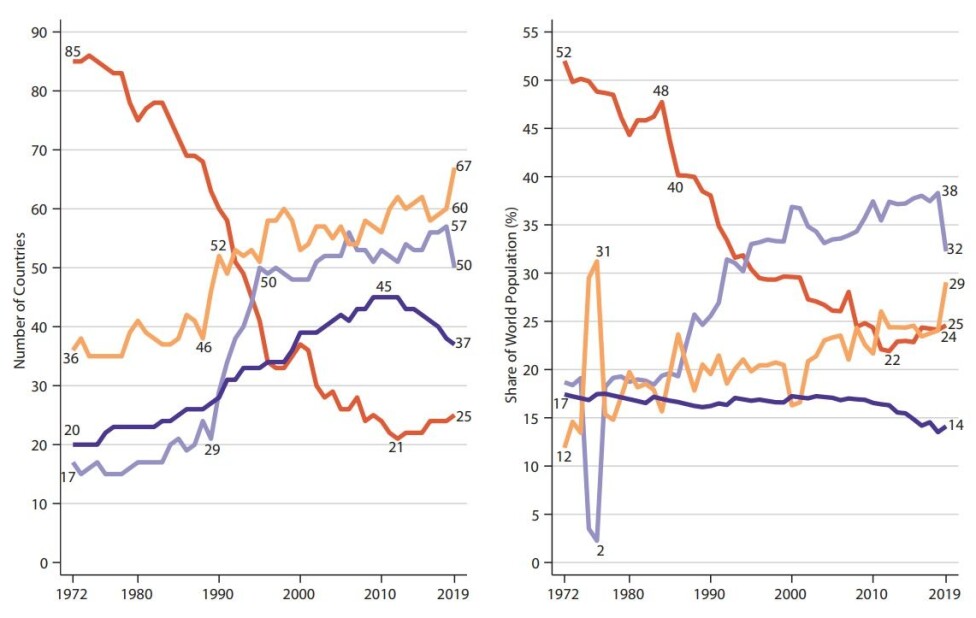

The figure below displays countries with different forms of government (from North Korea's closed autocracy to the Nordics’ liberal democracy) on the left-hand, and the proportion of the world's population living under the various forms of government on the right.

The regimes attempt to dominate the interlocutors by depriving them of the opportunity for dialogue with the rest of the population and their peers.

Those we have spoken with have taken the consequence and seized the opportunity to flee. From their exile, they try to create a tolerable life, but most of all they wish to return to their home countries when – or if – the political conditions change.

For the intellectuals, criticism and the visibility of oppression are necessity for social conditions to change, but when the regimes are challenged, they cross a line from where it is not easy to return.

On the other hand, it breeds resistance when the regimes are forcing them to loose contact with family, friends and colleagues.

The intellectuals are fighting for 'the people'

Globally, the demand for liberation seems to be growing, because citizens increasingly do not identify with the values of authoritarian regimes.

The participants in our project are fighting for an existence where the goal is not to take over the power but to create communities with space for everyone, as Syna, a writer from the Maghreb in northwestern Africa, says:

“For me, it does not matter who is in government. It is only important that people, regardless of political views and ethnicity, can live in their own country. This is why I continue to write and express my opinions."

After the horrific experiences in their home countries, the intellectuals pay particular attention to injustice and oppression, and the need for a decent future for ‘the people', as Eduardo, a South American researcher, frames it:

“The people are what create a nation. It goes both ways. A good government needs the voice of the people, and the people must feel represented by the government. Making my country free again is something I am fighting for."

The attitudes and activities of Syna, Eduardo and their peers are rooted in a social consciousness that encourages them to fight rather than simply being victims of the regimes’ oppression.

Our findings show that it is simultaneously a way for them to regain a sense of the freedom and autonomy that the regimes are trying to seize from the people. This additionally makes it transparent that resistance even can take place at all.

Resistance: civil disobedience and public debate

According to the participants themselves, their ideals of freedom do not express an unattainable ambition, but it does require specific strategies in order to succeed. How, then, is this being done?

In their exile, they are at the periphery of the regimes’ control, from which a critique of power can take place. By insisting on human values in order to counteract the ‘impersonal‘ regimes, the intellectuals try to create awareness of human suffering.

The attitude is that another world is possible, where freedom of speech and cultural and intellectual rights represent a celebration of diversity – not a threat. This is a critical point of view, from which one can potentially change social conditions, we are told.

Several of the participants experience that open conflict will often end up by reproducing the same agendas as before. For this reason, they do not always express their views as direct confrontation.

In order to reveal tensions, they make use of their many capabilities in a repertoire consisting of e.g. satire, theatre, social media, civil disobedience, public debate and academic dissemination of knowledge.

For example, the journalist Umud and his colleagues have started using for them the untraditional tool of social media, where they write under different aliases.

They are constantly changing their online names due to the fact, that the regimes zealously are persecuting them on the Internet.

Likewise, resistance is exercised by not showing the regimes the respect they expect to receive, or by simply ignoring authorities.

This can be an effective strategy to achieve social change, several participants express, because it shifts the focus away from the needs of those in power to what people will not accept.

How we can help

For several reasons, exiled intellectuals lead an insecure life. In one sense, they belong to a global elite, but at the same time, their future both in their home country and in their host country is uncertain.

Through their actions and attitudes, the intellectuals show that resistance to the regimes is possible, but as the project’s findings also show, it does not happen without dire consequences, as it puts themselves, family, friends and colleagues in danger.

However, the desire for social change is so strong that they are willing to risk their career in their home countries – and sometimes even their existence.

Therefore, we need to develop knowledge and methods in order to help these dissidents.

From their exiled position, they may be able to succeed in creating new social structures beyond the nation state. They are convinced that freedom can be achieved, but this requires a number of conditions. And it is precisely here that host countries can make a difference.

Our project points to a number of conditions that the intellectuals need:

• At the individual, social and professional levels, they are dependent on both moral and practical support from the international community

• To seek out networks and find employment locally or globally within their subject areas, it is necessary to participate in more international events such as conferences, exhibitions and festivals

• To continue their critique of the systems from a relatively protected position, they need to be invited to a host country and to stay there for as long as required – sometimes for the rest of their lives

• The host countries and organizations that facilitate help for the intellectuals must become better at cooperating, also with the intellectuals themselves

A free world requires aid to those who dare to fight

The findings show that the intellectuals in this study are able to navigate in uncertainty thanks to being invited to a host country. This additionally reinforces a sense of belonging to a global community beyond the authoritarian regimes.

Host countries and ‘the free world’ have an interest in helping the public intellectuals, for without such dissidents there is no critique of unsound, systemic structures and discourses. If we want a democratic and egalitarian world, we need to better support those who, often with their lives at stake, dare criticize the power mechanisms.

Ideally – at least from the point of view of the intellectuals – the regimes will lose their legitimacy, and the oppressive structures that once seemed as unquestionable as the laws of nature will seem outdated and inappropriate.

The project is in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals numbers 10 (less inequality), 16 (peace, justice and strong institutions) and 17 (global partnerships for capacity development).

Read the Danish version at Videnskab.dk's sistersite Forskerzonen.

References:

Christian Franklin Svensson's public profile

'The trickster of exiled intellectuals: Arcane opposition to the perceived injustice'. Anthropological Notebooks, 2020

'The problem of context in social and cultural anthropology'. Language & Communication, 2002

Arts Rights Justice (ARJ) Online Library

The Variety of Democracy Reports (V-Dem Institute)

UN’s Sustainable Development Goals

Book series: 'Gender, Development and Social Change'

Rule and Resistance Beyond the Nation State. Rowman & Littlefield International, 2019

‘When the revolution becomes the State it becomes my enemy again’: an interview with James C. Scott. The Conversation, 2018