Tests for pelvic joint pain not reliable at all

Some pregnant women are more sensitive to pain than others and end up being wrongly treated for pelvic joint pain, study shows.

New Danish research shows that some pregnant women diagnosed with pelvic joint pain might simply just be more sensitive to pain and not actually have loose pelvic joints.

Doctors currently diagnose pelvic joint pain by carrying out a series of tests, all of which are based on measuring where and when a pregnant woman feels disabling pain.

The pain is assumed to be an expression of the fact that the woman’s pelvis and joints are excessively hypermobile -- that is to say loose.

However, according to a new study from Aalborg University, this approach might be completely wrong.

“These tests are no good on their own. It’s wrong to talk about pelvic joint pain and pain in the same context,” says PhD student Thorvaldur S. Palsson.

“It’s in no way unusual to experience pain in the pelvis during pregnancy, because the pelvis and its joints soften and loosen in all women in preparation for birth. However, some women experience such excruciating pain that they are unable to lead a normal everyday life and it is this that is often inaccurately referred to as symphysis pubis dysfunction,” he says and continues:

“We thought the pain occurred because the joints and pelvis in pregnant women were too loose. Clinical tests were then carried out to ascertain whether they actually were suffering from pelvic joint pain. We now know, however, that these tests reveal how much pain the woman experiences and how sensitive she is to pain and not to how much the bone moves.”

Together with Professor Thomas Graven-Nielsen, Palsson has carried out a series of studies which underpin this assertion. The studies have been published in the scientific journals PAIN and The Clinical Journal of Pain.

Injected saltwater into healthy pelvises

The researchers started by exposing a group of healthy non-pregnant individuals, both men and women, to an experiment in which they injected a strong saline solution into the joints around the test subjects’ pelvises. This subjected them to pain which lasted some ten minutes.

The subjects then underwent the tests on which doctors routinely diagnose pelvic joint pain in pregnant women. The results of these clinical tests were positive, demonstrating that they had no bearing on loose joints or pelvis.

“Obviously, a healthy man doesn’t suffer from pelvic joint pain,” says Palsson.

Pregnant women exposed to pain test

In another experiment, the researchers tested a number of pregnant women’s sensitivity to pain. The researchers knew nothing about whether the women were having a painful pregnancy. The women were not asked about this until their sensitivity to pain had been measured.

A comparison between how much pain they experience during pregnancy and their sensitivity to pressure suggested that the women who were most sensitive to pain were also those who were experiencing a lot of pain during their pregnancy.

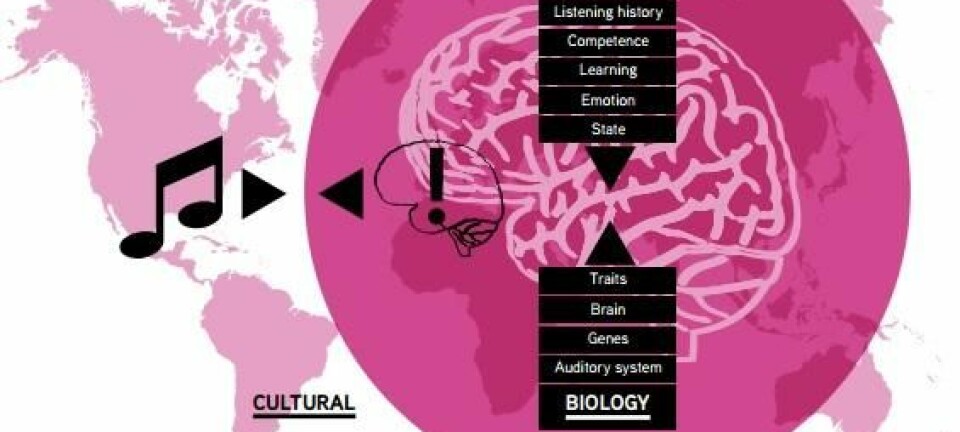

“We also discovered that the pain could give rise to heightened pain sensitivity in areas not affected by pregnancy. This may be because the pain mechanisms of the central nervous system become more sensitive. This is also known as neuroplasticity,” says Nielsen, who explains that the researchers also tested the women’s sensitivity to pain in their shoulders, which are not affected by pregnancy.

Mental health played a role in sensitivity to pain

Questionnaires completed by the women also told the researchers that the women’s experience of pain might be linked to their psychological and social conditions.

Pregnant women who slept badly at night and tended to get depressed were more sensitive to pain than pregnant women who slept well and enjoyed sound mental health.

Palsson believes that the new knowledge means that pregnant women experiencing strong pain should be offered other forms of treatment than those currently offered. These days, if a woman is diagnosed with pelvic joint pain an attempt is made to stabilise her pelvis using a special belt. But this by no means helps all of them and some women even feel more pain.

“This emphasises how little we know about the underlying causes of pain,” says Palsson.

Instead we ought to examine the correlation between the woman’s biological and psychological health, he says. We should, however, determine whether a pregnant woman sensitive to pain is also particularly sensitive to pain early in their pregnancy before they develop these pains, says Palsson.

Professor: pelvic joint pain may be caused by many factors

Professor Niels Uldbjerg of the Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics at Aarhus University Hospital in Skejby is not surprised by the research results from Aalborg University.

“We’ve never delved deep enough into what actually causes symphysis pubis dysfunction. Some studies say one thing, while others say another,” he says and continues:

“But the fact that some women have a lower pain threshold than others certainly might fit the picture, which may consist of several elements -- perhaps also including a looser pelvis.”

Uldbjerg agrees that a woman’s psychological state may be a relevant factor as far as pelvic joint pain is concerned.

“Actually, I think we’ve always had a hunch that a psychological element might play a role here. It’s only natural that people who are not so thick-skinned and who are heavy at heart are less robust when it comes to pain,” he says.

He points out, however, that the pregnant women most sensitive to pain in the second experiment might be extra sensitive precisely because they slept badly at night or entertained negative thoughts and not because they were generally sensitive to pain.

Translated by: Hugh Matthews

Scientific links

- Experimental pelvic pain facilitates pain provocation tests and causes regional hyperalgesia.

- Experimental Pelvic Pain Impairs the Performance During the Active Straight Leg Raise Test and Causes Excessive Muscle Stabilization.