Do neurons alone cause consciousness?

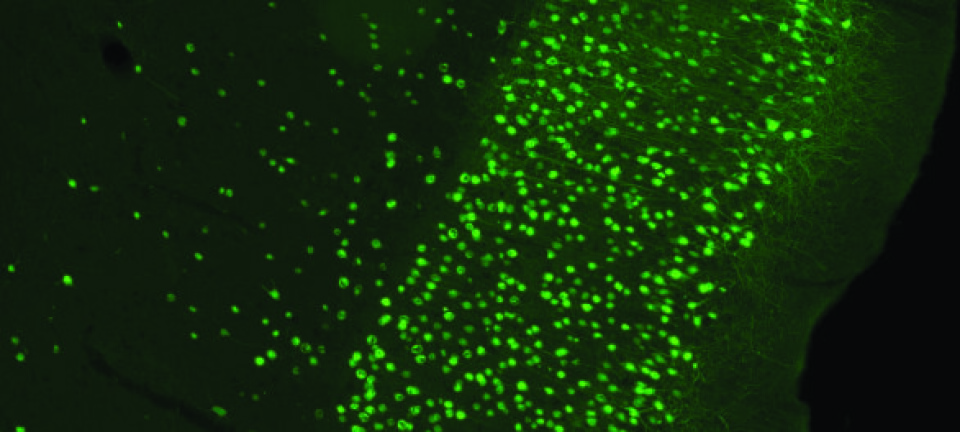

Our thoughts and emotions may not only be controlled by the brain’s neurons. Study sheds new light on how the brain works.

Brain scientists have long assumed that mental functions such as consciousness, thoughts and emotions were governed entirely by the brain’s neurons.

This assumption was based on the idea that the electrical signals in our neurons were the only ones quick enough to give rise to our mental activity.

Now a new Danish study shows that the astrocytes, which are also present in the brain, have responses that are almost as quick as those of the neurons. This, argue the researchers, means that the astrocytes may also play a part in thinking and feeling.

“Our study suggests that it’s no longer right to study the brain’s mental functions without also taking the astrocytes into account,” says Barbara Lykke Lind, a postdoc researcher at the Department of Neuroscience and Pharmacology at the University of Copenhagen.

Our study suggests that it’s no longer right to study the brain’s mental functions without also taking the astrocytes into account.

“One might be tempted to say that our findings open up for a better understanding of how the brain works and how mental phenomena arise.”

Lind was the lead researcher in the new study, which is published in the journal PNAS.

Brain research needs new approach

The common belief among neuroscientists has been that all cell types in the brain other than neurons are too slow in their communication to serve any other purpose than to provide nutrients to the neurons. However, according to Lind’s study, this may not be the case:

“It was thought that astrocytes only responded after many signals between the neurons – i.e. a reaction time of several seconds. This is too slow to play any direct role in the creation of mental phenomena.”

It is a challenge to convince other researchers that this study is solid and that astrocytes could actually be a much more significant component of brain function than we thought.

The new study shows that astrocytes in mouse brains have fast responses in addition to the slow:

“The cells actually respond with a speed believed to be sufficient to play a direct role in the creation of mental phenomena,” says Lind.

Astrocytes have more complex connections

Astrocytes have far more complex interrelations than neurons do.

“Some researchers believe that the astrocytes’ complex interconnections could help explain not only some of the mental phenomena that are hard to explain, such as thoughts and emotions, but also some of the diseases that are difficult to treat,” says Lind.

It is too early to say whether astrocytes actually play a direct role in mental phenomena, but our findings suggest that it is very likely.

This study focused on the cerebral cortex, the area of the brain responsible for the higher cognitive functions. However, other studies have indicated that the quick response of the astrocytes also takes place in the cerebellum and the hippocampus, which are associated with memory.

”It is starting to look as if the astrocytes can respond quickly and possibly be directly involved in our mental functions.”

A strongly-held belief

It has been a strongly-held belief in research circles that astrocytes do not play a major role in brain signalling:

”It is a challenge to convince other researchers that this study is solid and that astrocytes could actually be a much more significant component of brain function than we thought.”

In fact, the assumption that astrocytes respond slowly has been so strong that when scientists have observed a quick response from the astrocytes, this has been attributed to noise in the measurements.

Research treasure trove opened

Although the new study shows that astrocytes respond more quickly than previously assumed, there is room for a lot more research in this area:

”It is too early to say whether astrocytes actually play a direct role in mental phenomena, but our findings suggest that it is very likely,” says Lind.

------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk