Possible breakthrough in solar energy

New research opens up for more efficient ways of converting solar energy into electricity. This could be a major breakthrough in solar energy.

When the sun’s rays are converted into electricity that we can use in our houses, some 70 percent of the energy goes to waste.

This waste poses a great problem for solar energy as a renewable energy source – but now a more efficient technique might help solve that problem.

The solution is based on research by Professor Sergey I. Bozhevolnyi and his colleagues at the University of Southern Denmark in collaboration with researchers from Aalborg University.

Their findings have just been published in the international journal Nature Communications.

The new technique, which is based on nano-optics, makes it possible to use metals to convert light to electricity with very little waste. In other words, this opens up for a completely new way of producing solar cells.

Black metal with nano focusing

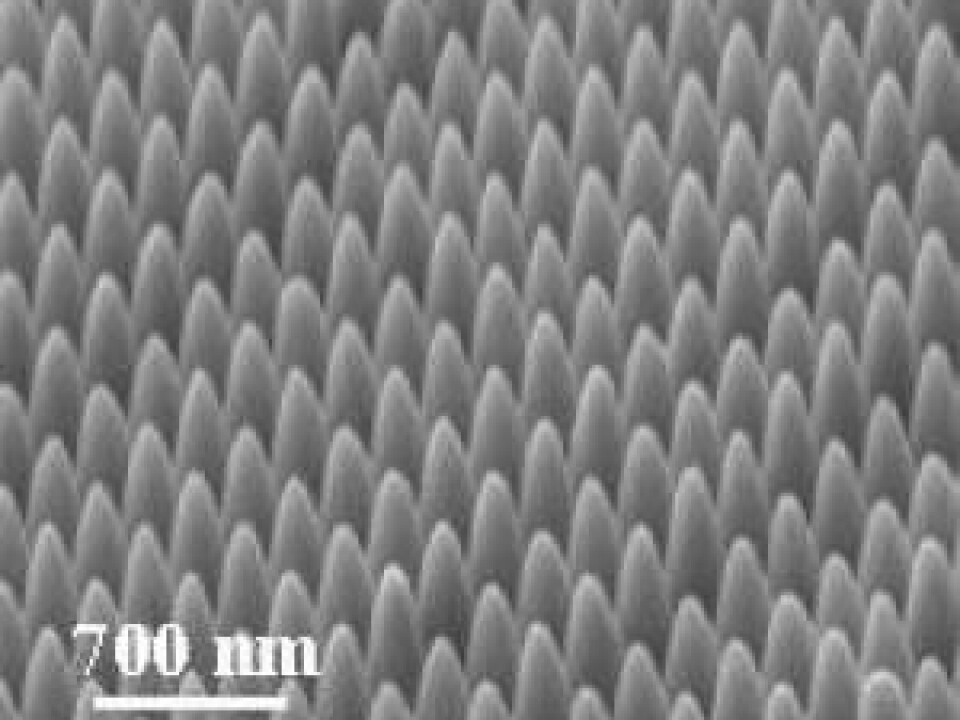

The scientists have come up with a new approach to converting shiny metals such as gold, silver and platinum into black metal by changing the nanostructure of their surfaces.

When the surface of the metal is black, it means that most of the light that hits the surface is absorbed by the metal because the dark surface converts the light into heat.

This is currently not a cheap solution, but it’s much more efficient than traditional methods.

If we optimise the method, we can solve the waste problem associated with solar energy.

Up to now it has only been possible to create black metal by destroying the metal surface with intense laser light, which generates soot particles and other random particles.

Previous systematic solutions have only made use of light absorption with a very limited range of wavelengths, resulting in a waste of energy.

The Danish researchers have focused on a so-called nano-focusing of the light – a method that has only been around in the past ten years.

“This means that light is constantly being forced into a narrow metal groove until it stops and becomes absorbed,” says Bozhevolnyi. “This focusing makes for extremely efficient light absorption, with about 96 percent being absorbed in a wide range of wavelengths.”

New technique reduces waste

There is a variety of possible applications for this new method, but the professor sees particularly great potential in the area of 'thermophotovoltaics', a direct conversion process from heat differentials to electricity by means of photons from sunlight.

Generally speaking, the light emission from the various heated materials will be the same, colour-wise, as the spectrum they absorb.

This means that if the surface only absorbs blue light, it will in principle only be able to emit blue light when the material is heated. Black surfaces, on the other hand, can absorb a very broad spectrum of light.

“Our black metal will greatly increase the efficiency of the heat generated in the energy conversion process. This will make it possible to use our technique as compact energy-saving electric generators with no moving parts,” says the professor.

He believes the method could prove to be a much better way to convert solar energy to electricity than what we have today.

“There are clear signs that ordinary solar cells are less efficient than the type of generators we’re working with. If we optimise the method, we can solve the waste problem associated with solar energy,” he says, pointing out that there is a fundamental maximum limit to how efficient conventional solar cells can be.

Next step: a cheaper solution

Bozhevolnyi and his team are hoping that the publication of their new findings will play an important role in the future.

“Our conclusions will inspire other scientists working in the same field to further develop our concept,” he says.

”The next step consists of studying other cheaper metals so we can continue to work towards a solution that can be used in practice. We’ll also be on the lookout for more efficient ways of manufacturing these surface structures.”

------------------------------------------------

Read this article in Danish at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther