What gives a Xmas song the X factor?

White Christmas, Blue Christmas, Last Christmas ... it's the same Christmas songs that you hear endlessly repeated on the radio and in shopping malls every year. But what is it that makes these songs so enduringly popular?

‘Last Christmas, I gave you my heart, but the very next day …’ A festive group of teenagers swaying through the music-filled shopping mall suddenly exclaim in noisy chorus: ‘you gave it away!’

Wham's 1984 hit is just one of a vast catalogue of classic Christmas songs that many of us have known since we were kids. We have heard them so often down the years that we know most of the words by heart.

But why are we happy to go on listening to the same old songs year after year? And what does a Christmas song need to become a hit and join the parade of classics that are endlessly played throughout the festive season?

ScienceNordic turned to Peter Vuust, who has the perfect credentials to supply the answers. For he is not only professor at the Royal Academy of Music and a jazz musician, but also Associate Professor at the Center of Functionally Integrative Neuroscience at Aarhus University.

No magical recipe

Vuust is quick to point out that there is no magical recipe for guaranteeing that a song has all the right ingredients to become a Christmas hit.

"If there was one, I wouldn't be working where I am now," he says with a smile.

But although there is no fixed formula for success, it is still possible to find reasons for why certain Christmas songs have staying power, and why we are happy to keep listening to them.

Repetition matters

Vuust explains that there is a self-perpetuating effect in hearing the same Christmas songs year after year. Our brains function so that the more times we hear something, the more we like it.

"That is very much the case with Christmas songs, which we hear over and over, year after year," says Vuust, who has conducted experiments where a piece of music was played to groups of test subjects. The number of times the music was played varied between the groups, and when the subjects were asked afterwards, those who had heard the music the most times also liked it the most.

This finding explains a common phenomenon when a new single is played on the radio and your first reaction is 'what a load of rubbish'. Yet three weeks (and plenty of replays) later you find yourself humming the self-same song.

Prediction rewarded

There is a scientific explanation for why the brain likes repetitions, which is based on our natural instinct to try to see ahead and predict what will happen.

If we correctly predict something, the brain releases a small burst of dopamine, which functions as a sort of narcotic reward for the body. When we hear the first notes of a song, our brain works hard to recognise it. If we quickly identify the song and which notes or lyrics come next, we experience a specific reward a moment later when our prediction is confirmed.

The smart thing about Christmas hits is that you forget them, and then start afresh on the upward curve when the festive season comes round again

"It's the brain's way of making sure that we do something which is good for our survival," says Vuust. "Music is well suited to the brain's prediction and expectation mechanisms, because it is so precise in time that the brain can constantly formulate expectations which become reality moments later."

The brain-pleasing technique of using repetitions is also employed in the composition of the songs themselves. In Wham's 'Last Christmas' for example, the chorus is repeated no less than six times, and takes up more than a third of the song's entire length.

The seasonal effect

Not everyone likes Christmas songs, however. Some quickly tire of them, while others find them nauseating from the word go. But science also has an explanation for this negative reaction.

The upward-sloping curve, where we increasingly like a song the more times we hear it, often breaks at the moment we become conscious of the fact, says Vuust.

“As soon as we reach the conscious level, we start becoming critical – so the positive effect does not last forever. The smart thing about Christmas hits is that you forget them, and then start afresh on the upward curve when the festive season comes round again.”

The art of standing out

But more is needed than just the recognition effect to create a Christmas hit. If a song offers nothing more than pattern recognition, the brain establishes that there is no danger of something unknown and so does not react.

"A song must stand out in one way or another – if there is nothing new and different in it, we simply forget it," says Vuust. "That is why catchy songs often have what are called C pieces, which make a small break from the rest of the song. They don't have to be long, just sufficient to grab our attention."

In a song, the verse and chorus are called the A and B pieces, while the short break in the pattern is called the C piece. When the C piece is played, the brain's reward mechanism is again activated, but in another way – we get a shot of dopamine when something unexpected happens.

Layers and details

There are yet other ways in which Christmas songs differ from the rest. The lyrics, whether festive or sentimental, almost always centre on the obvious subject of Christmas. And whereas live sounds are rarely heard in ordinary pop songs, things like sleigh bells and church bells are more or less essential in a Christmas song.

Besides being filled with repetitions, bells and strange-sounding instruments, classic Christmas songs often have several layers more than the average pop song.

"They have to last for many years, and one can generally say that songs which survive for more than one season have many layers and details," says Vuust. Take 'Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas' for example – it's a finely composed piece. Simple on the surface, but with lots of layers to explore."

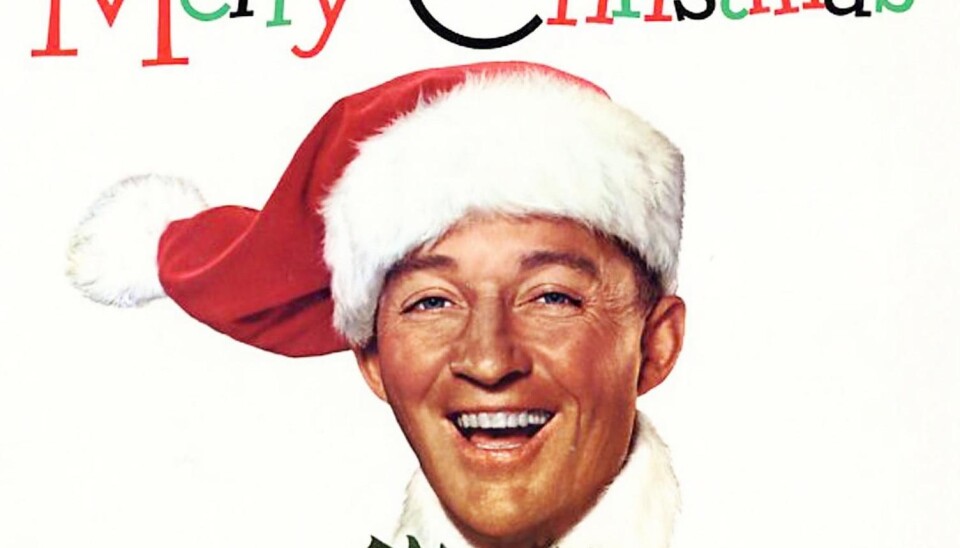

A final criterion for a long-lasting Christmas song is that the artist must be relatively well-known, and easy to associate with Christmas, believes Vuust. "We like the thought that it is Bing Crosby or Paul McCartney we are listening to. And it is easy to imagine someone like Bing Crosby wearing a Christmas hat."

Getting in the mood

The most important characteristic of music is that it affects our emotions. And in a similar way to Pavlov's dogs, which were conditioned to associate food with the ringing of a bell, we associate Christmas songs with certain feelings and experiences. That is one of the most important reasons why we like to listen to golden oldies, thinks Vuust.

"People can usually remember what music was playing when they kissed their sweetheart for the first time. Music is often tied to memories and feelings, so we quickly get into a certain mood when we hear it."

Translated by: Nigel Mander