Stem cells could fix a damaged heart

A new clinical trial could benefit heart patients who do not have any other treatment options left.

At age 54, Ole Christensen from Denmark, suffered a heart attack.

He had cycled straight from work to central Copenhagen, where he was supposed to meet his wife. They had planned to have dinner and enjoy the sunshine along one of the popular canals in the city.

“I parked my bike so that we could walk together. But during our walk I suddenly felt out of breath and felt that I couldn’t walk,” says Ole.

Soon after, he was in a week-long coma at Rigshospitalet. A small piece of material consisting of calcium, fat, and cholesterol had broken off from his coronary arteries and become stuck, causing a heart attack and turning his world upside down.

Today, nine years later, Ole has returned to Rigshospitalet as a participant in a medical research study to help him and patients like him by injecting stem cells into their hearts.

Read More: Will we ever be able to grow organs in a Petri dish?

How to grow stem cells

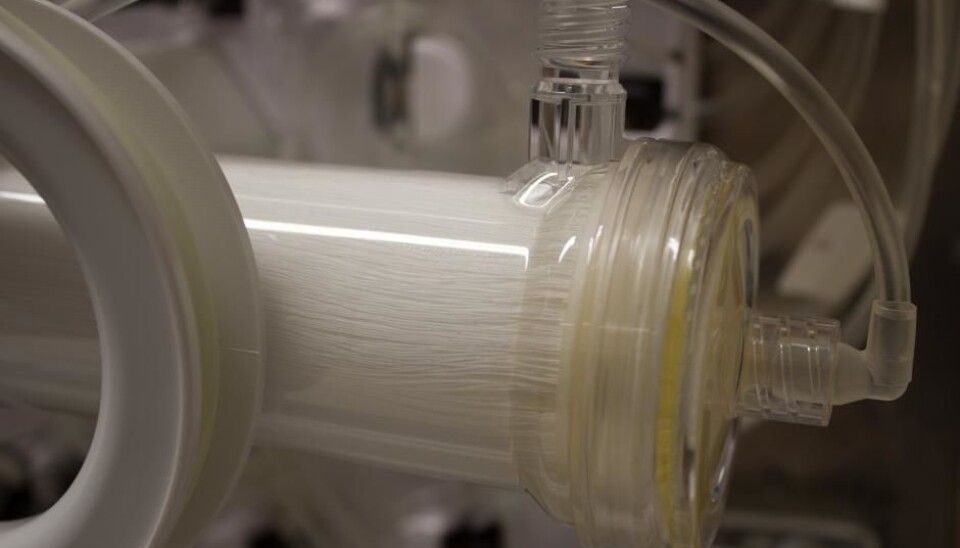

The stem cells for the trial are grown on the third floor of Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen. They grow and multiply inside four machines known as bioreactors, which look like sophisticated microwave ovens. Each one contains 11,000 thin straws, containing the stem cells.

The cells come from abdominal fat from young healthy donors. Inside the bioreactors, the stem cells are fed a nutritious, red liquid, which enables them to multiply.

“When we harvest the stem cells we usually take 50 to 200 millilitres of abdominal fat from the donor. But there are many different kinds of cells in the fat, so we need to separate the stem cells from other types of cells,” says Professor Jens Kastrup, a cardiologist at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen.

Kastrup first roughly sorts the cells using a centrifuge. He then places the cells inside the bioreactor, where the stem cells adhere to the straws while all the other cells fall to the bottom and are flushed out with the continuous medium flow through the straws, he says.

Previously, stem cells were harvested from each individual heart patient. However, today, researchers have refined the technique enabling them to use donor cells.

The human body does not recognise these so-called mesenchymal stem cells as a dangerous foreign body and so does not reject them, despite the fact that they originate from another person and were grown in a machine.

Read More: Danish scientists about to begin first ever stem cell trials on humans

No other treatment options left for Ole

Ole is typical of the type of heart patient Professor Kastrup hopes will benefit from the stem cell treatment.

Over the years, Ole has tried everything to treat the damage caused by his heart attack -- both medication and operations. It has saved his life, but his heart is now so damaged that his heart can now only pump at one third of the normal rate.

”It means I always feel very tired. If I lift something heavy, I become terribly breathless.”

Having been told there were no other treatment options available for him, he contacted Kastrup's team after reading about the trial in the local paper.

Read More: Protein that controls DNA packing identified

Stem cells injected into the heart

In December 2016, Ole went on the operating table at Rigshospitalet to have stem cells injected into his heart.

Kastrup administered a local anaesthetic before cutting a small hole in Ole’s groin, to pass a catheter with a needle through the main artery and up to Ole’s heart.

”I was awake during the whole operation, but I was sedated which helped me to lay still. There were an awful lot of people in the small room,” says Ole, as he recalls the three-hour long operation.

Through a 3D image of Ole’s heart, Kastrup identified the areas most affected by scar tissue and injected stem cells into the affected areas.

“When we started our research, we actually thought that the stem cells we injected into the patient would become new heart muscle cells or heart vessels,” says Kastrup.

“But it turned out that the stem cells probably act as a kind of factory, producing a lot of active substances. These substances stimulate the cells that are already in the heart. So, one can say that stem cells ‘inject’ life into the weak areas of the heart again.”

Read More: Harder to predict heart problems among smokers

Ole feels better, but is it just placebo?

The trial is a so-called double-blind, randomised clinical trial, which means that the participants are randomly allocated to one of two groups where they receive either a non-active treatment (placebo) or the real treatment. So neither Jens Kastrup nor Ole Christensen knows what was injected into Ole's heart during the operation.

Eighty people have taken part in the trial in addition to Ole. One third of them have received a placebo as a saline injection and the remaining two thirds received the real stem cell treatment.

”Before I agreed to participate in the experiment, I obviously considered the fact that I might have to undergo a major operation to only have saline injected into my heart. But that is the nature of research, and I am actually OK with that. There are no other treatment options for me, so the alternative would be that I don’t get anything injected into the heart--neither stem cells nor saline,” says Ole.

Read More: More heart attacks on cold days

High hopes for the treatment

Preliminary results show that stem cell treatment helps patients. However, the treatment has not yet been tested in enough people to determine the full effect.

”The patients we have treated so far with their own cells or patients treated with cells from healthy donors in a previous safety trial developed a better pumping function of the heart, they get more muscle mass and fewer problems when they do physical activity. We can also see from other tests that they have a better quality of life,” says Kastrup.

And Kastrup has high hopes for the treatment.

“Where it used to take us six to eight weeks to grow enough stem cells for a single patient, we can now grow enough stem cells for four to five patients in just one to two weeks. We can also freeze stem cells and save them to use later,” he says.

This means we will soon have a product which can not only be used for research, but is also a realistic treatment option for hospitals, he says.

So far the patients have only received a single dose of treatment, but Kastrup expects that multiple treatments would have further positive effects.

Read More: New stem cell discovery has great therapeutic potential

Heart patient: “I feel better”

The current trial is now at the penultimate stage before a possible approval as a standard treatment available in hospitals outside of a research context.

The stem cells from Rigshospitalet are also sent to Slovenia, Austria, Poland, Germany and Hollandas part of a parallel international study “SCIENCE” supported by the European Union.

“Stem cell treatment definitely has potential. There is a group of heart patients who cannot be adequately helped with our current treatment options, and who still have chest pain,” says Hans Erik Bøtker, a senior physician and clinical professor in heart disease at Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark.

“For them, it will be a big step forward if, in the future, we can help them with stem cells. We haven’t yet reached the finish line, but Rigshospitalet have done a lot of hard work and they deserve credit for that,” he says.

Ole will have to wait another three years when the study is complete to find out whether he received the stem cells or the placebo.

But he has already noticed an improvement.

“I actually feel better. I've got a little more energy and, physically, I can do a little more than I used to. But it might also just be a coincidence and maybe it has nothing to do with the saline injection or stem cells. I've had periods before when I've felt better than normal,” he says.

“But I hope it's because of stem cells. Then perhaps my good periods will last longer.”

---------------

Read the more in the Danish article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Katrine Bavnbek