Human implants are invaded by microorganisms

A multitude of microorganisms depend on human implants to survive, shows new research. Scientists do not yet know whether they have a health impact.

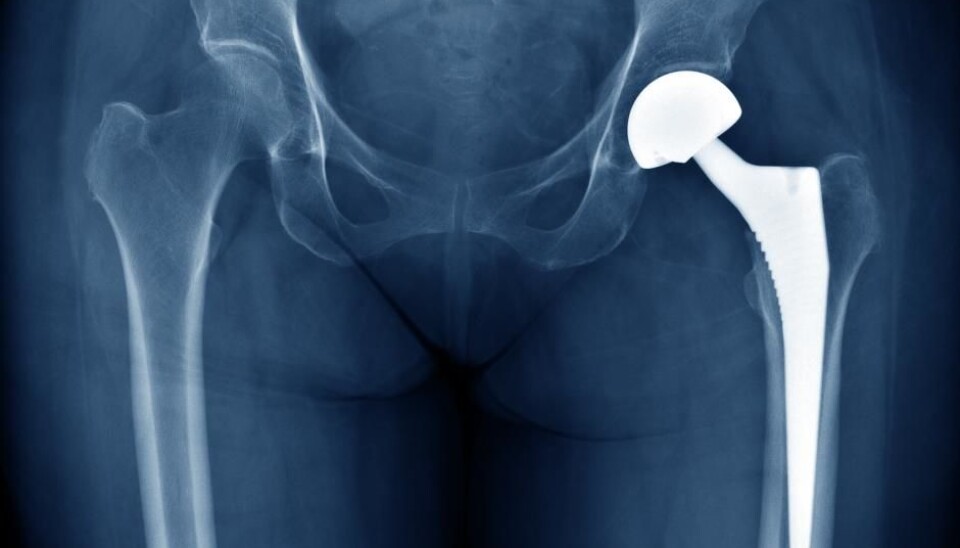

Once in place, human implants become colonised by bacteria and fungal species.

Even though the implants are entirely sterile when first used, they are nonetheless home to a number of naturally occurring bacteria in the body, shows a new study.

Scientists have previously studied microorganisms on implants surrounded by infected tissue, but this is the first time that they have studied this process in patients with no such complications.

“We didn’t know that they occurred in symptom-free patients. We’ve uncovered an entirely new niche for bacteria and fungi in people,” says Thomas Bjarnsholt, professor at the Costerton Biofilm Center at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark. He is the senior author on the new scientific article published in the Journal of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology.

Read More: How our gut influences our health

New niche of microorganisms

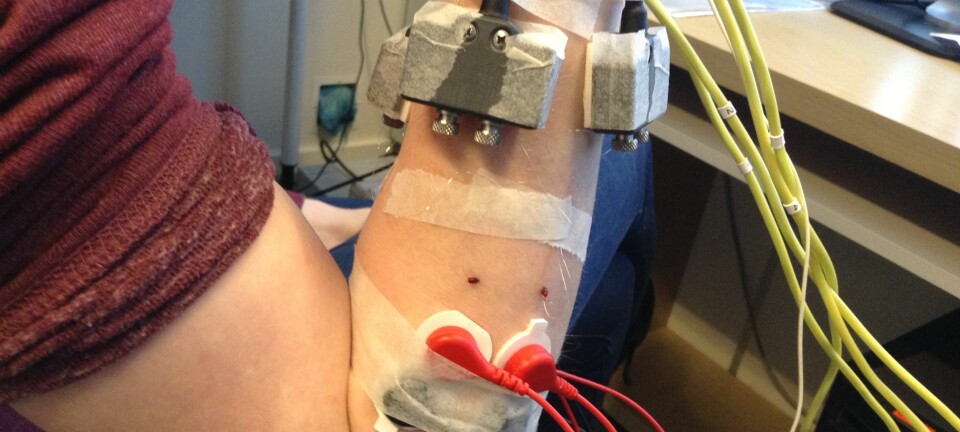

In the study, scientists removed implant parts (screws from joints and bones, parts of pacemakers, and plates from skulls) from patients who were due to have them removed anyway.

They also took whole implants out of recently deceased patients, who had no infection around the implant at the time of their death.

In total, they collected 106 implants from infection-free patients.

They studied a further 39 implants as controls for their experiment—to see where the microorganisms originated, either in the body, during surgery, or in subsequent follow-up surgeries.

Implants were removed from their packaging and implanted into the body for 20 seconds before being removed, and sent for analysis.

They also analysed a few other, unused implants that were fresh from their packaging to ensure that they were not just analysing contamination by mistake.

The results showed that:

- 70 per cent of the regular implants were colonised by multiple strains of bacteria and fungi.

- These bacteria were not harmful and the immune system had not gone into attack mode.

- The control implants were entirely free from microorganisms.

The study does not show how long it takes these microorganisms to colonise the implants.

Read More: Space travel changes gut bacteria in mice

Surprising results

“I didn’t think we would find anything, it was totally unexpected,” says lead-author, Tim Holm Jakobsen, assistant professor at the Costerton Biofilm Center at the University of Copenhagen.

Even though their analyses revealed microorganisms on a little over two thirds of implants, it is likely that all implants are covered in microorganisms, says Jakobsen.

In this study, Jakobsen and colleagues were not able to remove full implants from living patients, for practical reasons. But, they say, there may well be bacteria on other parts of the implants that they were unable to analyse.

“We know that the bacteria are heterogeneous, and we have only tested a fraction of the implant. So, we may have missed one of the areas where bacteria are located,” says Jakobsen.

Read More: Gut bacteria keeps bears healthily obese

The human body is not sterile

The results indicate that the human body is not the sterile environment that many imagine it to be, says Mogens Kilian, professor emeritus at the Department of Biomedicine, Aarhus University, Denmark. He was not involved in the new study.

The bacteria probably reached the implant via the blood stream, he says.

“Even though we’ve long known that humans are colonised by microorganisms, we previously thought that our blood and tissues were sterile. This has proved to be wrong, as we’ve discovered bacteria in blood originating from the oral cavity, gut, and skin” says Kilian.

“This study supports the idea that our inner parts are not always sterile, and this does not necessarily cause problems.”

Read More: Scientists surprised to find bacteria inside fallopian tubes and around ovaries

Microorganisms can protect against infection

The new study does not reveal how the microorganisms could impact human health. But it could be positive.

The bacteria identified are known to be harmless in their natural habitat. The study suggests that this may be the case also when colonizing foreign bodies. They may even help keep other harmful bacteria away, says Kilian.

According to Bjarnsholt, the new results raise even more questions.

“Who knows what role bacteria and fungi play when they live on implants, if any? They may protect against harmful bacteria. Perhaps they are the reason why implants can exist in the body at all,” he says.

“Maybe we can prevent chronic infections by allowing certain bacterial species and fungi to grow on the implant before it is implanted. That would be great.”

----------------

Read more in the Danish version of this article at Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex