Scientists send world’s fastest data signal

Scientists have set a new world record: the largest amount of data, equal to twice the world’s daily Internet traffic, sent through a single fibre cable.

An international team of scientists has broken the world record for the most data sent through a single fibre optic cable: 661 terabytes per second.

“It equates to more than double the world’s total Internet traffic, which is around 300 terabytes per second each day,” says co-author Leif Katsuo Oxenløwe from the research centre for Silicon Photonics for Optical Communications (SPOC) at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU).

The results were recently presented at the Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics (CLEO) in San Jose, USA, and may be an important step towards reducing global energy consumption associated with the world wide web.

“Communications technology now accounts for about 10 per cent of the world's total consumption of electricity, and it grows exponentially by at least 30 per cent every year. So we have to develop technologies that can reduce this energy consumption,” says Oxenløwe.

This increase is almost entirely due to the expansion of the Internet and the millions of electronic components, cabling, and data centres required to keep it running.

New technology to replace thousands of energy guzzling lasers

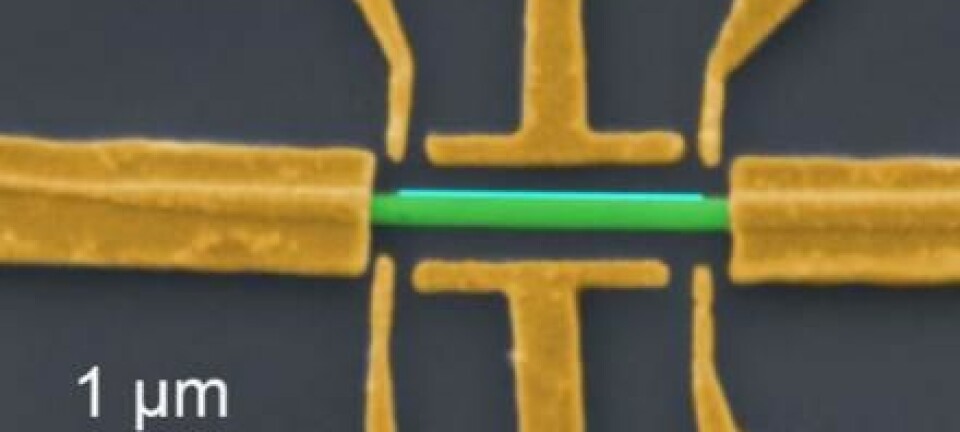

Information sent over the Internet consists of small infra-red flashes of light, emitted by lasers at opposite ends of fibre optic cables.

A typical data centre may contain around 100 lasers, carrying almost 100 gigabytes of information a second. Each of these lasers and their components consume power, but based on the new record the scientists’ ambition is that this data could be sent by a single laser.

“At the rate that we achieved with one laser, we could scale back the thousands of lasers currently used. It’s one way of reducing energy consumption,” says Oxenløwe.

Read More: World's fastest chip could make the Internet eco-friendly

A long way to go before being implemented

Andrew Ellis, a Professor of Optical Communications at Aston University, Birmingham, UK, saw the results presented at CLEO Conference.

“It’s a very impressive record,” says Ellis, but he emphasises that the technology will not be implemented for quite some time yet.

“It’s a far cry from the technology we have today and it’s hard to see that far into the future,” he says.

“Personally, I think that this kind of technology will be part of the Internet’s future infrastructure, but by then we will see less complex solutions. The industry is quite conservative.”

Read More: Scientists move closer to developing a quantum computer

We need energy efficient solutions

Ellis shares Oxenløwe’s concern for the web's exponentially increasing energy consumption.

“We face a great challenge, and it places great demands on energy efficiency. Experiments like DTU’s are only part of the solution, and it has its own challenge to exchange several hundred lasers for one,” says Ellis.

He also sees potential complications when relying on a single laser.

“If the laser fails, it’s suddenly a much bigger disaster than today, where you have many lasers in each data centre. So you’ll need multiple backups if the technology is to be implemented,” he says.

Oxenløwe agrees.

“It’s true that you’ll need to have two or maybe three backup solutions ready if things go wrong, but the new technology will still represent a big energy saving,” says Oxenløwe.

But certain changes could be made earlier.

To realise the speeds DTU has achieved will require a major overhaul of the Internet’s infrastructure, and for a start, new types of fibre optics will need to be laid.

“We’re approaching the point of maximum capacity of existing fibre optics, so we must begin to consider what kind of fibre we want to lay in the future. This is clearly an opportunity to start using multi-core fibre,” says Ellis.

-------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex