Researchers' Zone:

Suicide and ship hijacking: Join the Asian Company on a dramatic journey to India in the 1700s

Dive into the Asian Company's extensive archive packed with exciting and detailed descriptions of life aboard the huge ships.

For much of the 1700s, the Asian Company, a Danish trading company, had a monopoly on trade with India and China.

At the time, this was Denmark's largest enterprise, and fortunately they left behind a host of travel accounts hidden away in the Danish National Archives, where I take my daily walk.

Now I would like to take you with me to explore some of them. Let us start with a story of the death of a ship's cook.

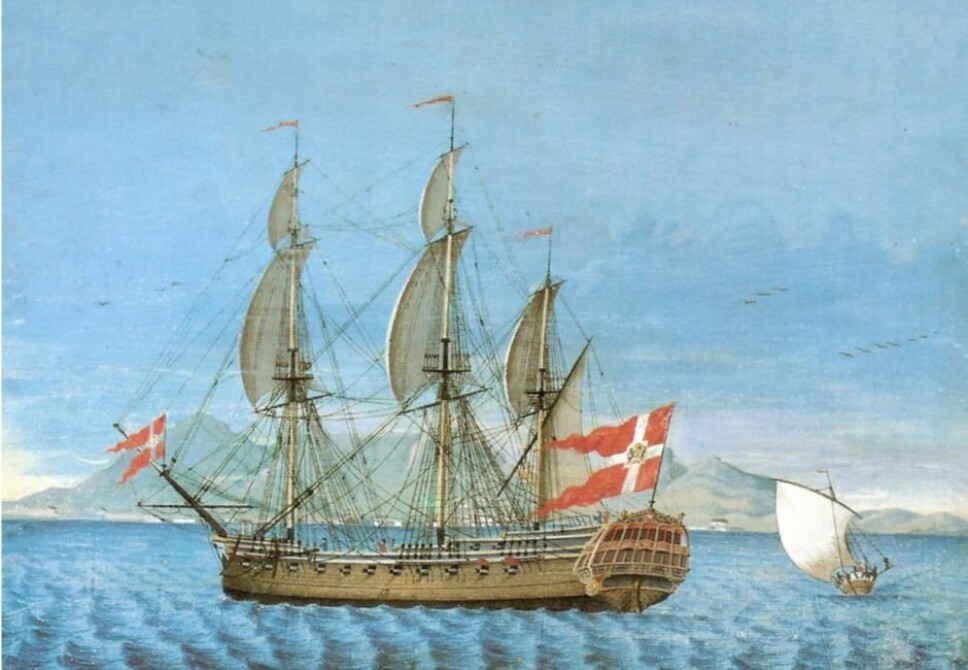

Hans Hendrich Gotberg was a cook on the Asian Company's frigate The Crown Princess of Denmark, which, in November 1748, sailed out of Christianshavn and six and a half months later arrived at the Danish trading post of Tranquebar in South-East India.

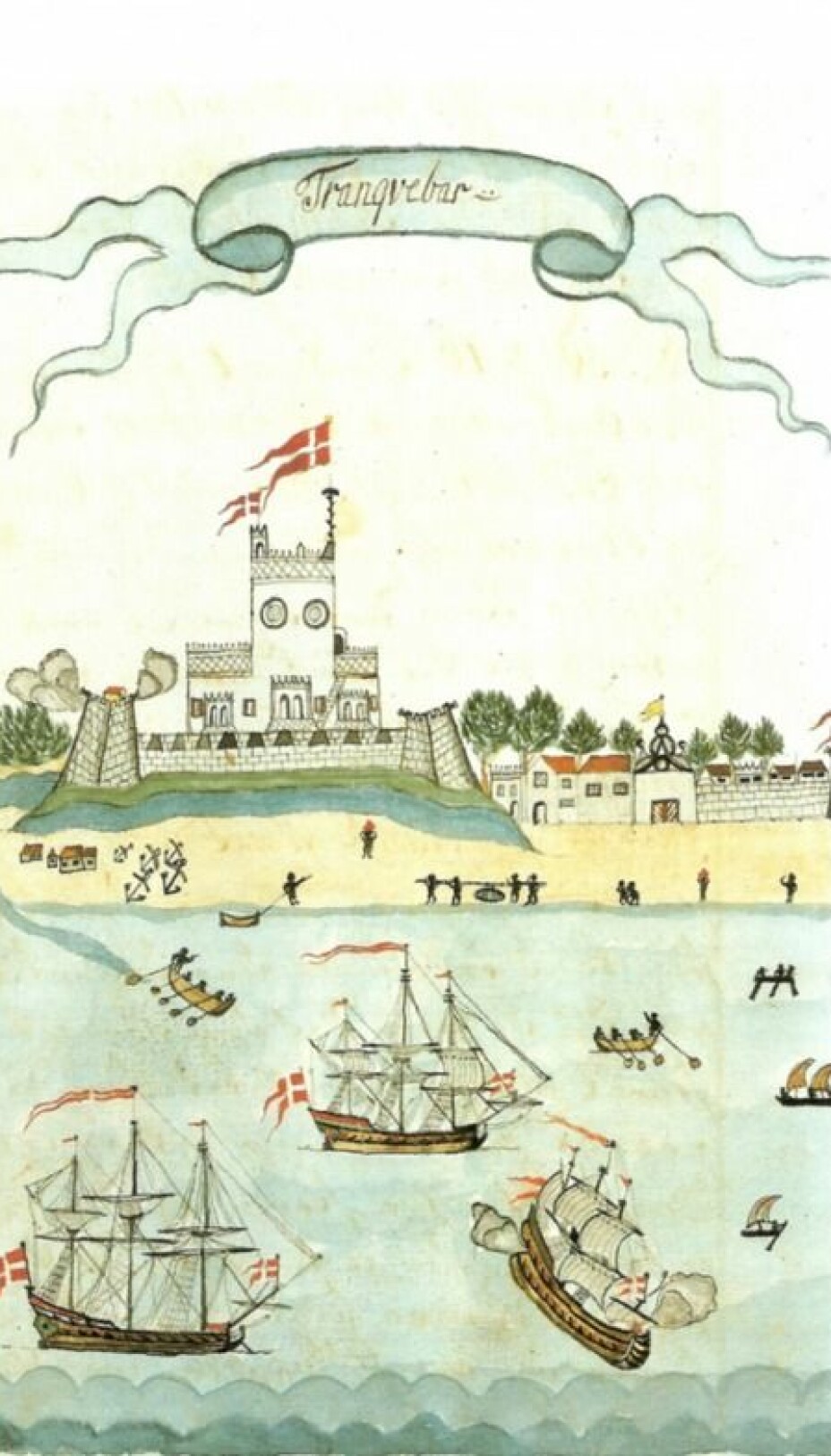

Tranquebar in 1723. The town had no port, and all transport to and from land had to be done by Indian rowing boats. The fortress of Dansborg rises above the town, and on the right, in the town wall, the seaport into the town can be seen. The drawing is from First Officer Schmidt's travel diary on board the ship Queen Anna Sophia. (The Royal Library, New Royal Navy. Collection 2168)

The journey was something of an ordeal for the other 125 men, for the food was so unappetising that many often left the table without eating anything. On several occasions, large linen cloths were even found in the food!

After a six-month stay in Tranquebar, the return journey began. When Gotberg continued where he left off, it became too much for the captain, who feared that many would fall ill or might even die because of the cook's irresponsibleness. As a result, the cook was summoned to the ship's internal court.

Here the judges agreed that he deserved a harsh, corporal punishment, for example 50 or 60 strokes with the cat o' nine tails, a whip with nine rope ends, and he should also be stripped of a month’s wages. This did not come to pass, however, because, just five hours after the first hearing, Gotberg threw himself into the sea.

A wealth of research opportunities in the Asian Company archives

The story of Gotberg can be found in the ship’s protocol conducted on the Crown Princess of Denmark’s expedition of 1748-50.

It is a combination of an official diary, court record, auction book with information about what the dead sailors left behind, and a copybook with transcripts of the letters that the captain sent home to the Asian Company's administrators during the voyage.

The National Archives' large archive of the Asian Company contains these kinds of protocols for the vast majority of the expeditions that the Asian Company conducted to India and China throughout the company's existence from 1732 to 1843.

The National Archives also has ship records, which are kind of logbooks, scrolls with name lists for the majority of the Asian Company's travels, protocols that illuminate the activities of the company's offices in Christianshavn, as well as some court records from the then Danish trading colony of Tranquebar and trading books from China.

Was keelhauling a common punishment?

The Asian Company has left behind a large archive, and it contains plenty of research opportunities that many historians have used.

Among other things, they have used it to study the company's finances, the equipment of the ships, the mortality on board, the possessions of the dead sailors and the population composition of Tranquebar.

One subject that could also merit further investigation is the administering of justice on board.

It might be interesting to see the extent to which the internal court of the ship followed the sentencing guidelines established by the Asian Company in its general legal rules, the ship's articles.

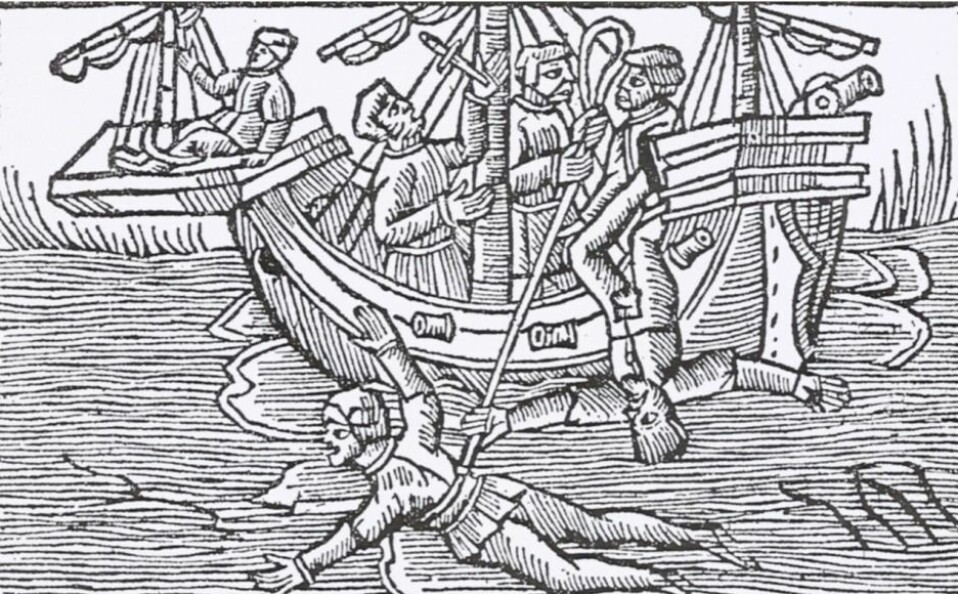

It is clear that many blows with the cat o' nine tails – the punishment intended for Hans Hendrich Gotberg – were quite common, but how often were the more serious corporal punishments such as keelhauling used, where one was dragged under the ship with ropes around one’s waist?

The ship Tranquebar's mysterious recapture raises suspicions of collusion

Another interesting piece of research is how the crews of the company ships handled unexpected events such as shipwrecks and hijackings.

Together with a Spanish historian, I am currently mapping out what happened when the Danish merchant ship Tranquebar was attacked in February 1763 by Indian pirates, the Maratha, on the southern part of the west coast of India, only a few days later to experience what might be called a 'recapture' by a Portuguese fleet.

The mysterious course may tempt one to believe that there was some collusion between the two parties, both of whom benefited greatly from it.

The Maratha got away with all the effects that were easy to transport, and in addition they took some of the crew as prisoners.

The Portuguese brought the ship to their trading station in Goa, where a local court found that it was a 'legal prize', i.e., a spoil of war, which had been legally acquired. After that, the Portuguese were free to make use of the ship, despite fierce criticism from the Danes.

The Maratha did eventually release the captured Danish sailors, but only after a battle of nerves over several months. Whether the Asian Company eventually paid a small ransom is a little unclear – at least so far, as our investigations are far from complete.

The Asian Company enjoyed huge success in the 1700s

The Asian Company was Denmark's largest enterprise in the 1700s.

It was organised as a kind of limited company, and, from 1732 to 1772, it had a Danish monopoly on trade in India and China.

The China monopoly was extended in both 1772 and 1792. Contrastingly, in 1772, individuals in Denmark, Norway, Schleswig and Holstein were allowed to equip ships for trade in India.

However, the Asian Company remained by far the most important Danish player in India until the war years of 1807-14, when the Danish long-distance trading came to a halt.

From 1732 to 1807, the Asian Company sent at least one ship to both India and China almost every year, and, in particularly good years, it could jump to three to five voyages.

Tea, porcelain and Indian cotton were imported in large quantities

The company benefited from an apparent increase in European demand for Asian goods, especially Chinese tea and porcelain, as well as Indian cotton clothing, and most of the goods brought home by the company were resold to other European countries.

Eigtveds Pakhus on Christianshavn, built in 1748-50, was the storage and auction site for many of these goods.

As price developments in Europe ran favourably for Indian goods from the mid-1740s, the Asian Company chose to intensify trade in India.

Initially, this was done by a more frequent service to Tranquebar, where Denmark had had trading activities since 1620, but in the years 1752-56, three small trading sites were also set up in Colachel and Calicut on the South West Indian coast, as well as in Serampore, also called Frederiksnagore, in Bengal.

Colachel and Calicut were important purchasing sites for pepper for a number of years, but they languished after 1780. Serampore, on the other hand, developed into a significant centre for trade in cotton, silk clothing and potassium nitrate, and, at the end of the 1700s, Serampore became the most important Danish trading post in India.

In 1845, both Tranquebar and Serampore were sold to the British East India Company, the largest of the many European trading companies operating in India at that time.

And that also marked the end of a unique period in Danish trading and maritime history.

———

Translated by Stuart Pethick, e-sp.dk translation services.

Read the Danish version at Videnskab.dk’s Forskerzonen.

References:

Jørgen Mikkelsen's profile (The Danish National Archives)

And the following three Danish publications:

- 'Sejllads mellem København og Tranquebar'. Selskabet for Udgivelse af Kilder til Dansk Historie i samarbejde med Handels- og Søfartsmuseet (2011)

- 'Kinafarerne. Mellem kejserens Kina og kongens København'. Gads Forlag (2019)

- 'Danmark og kolonierne: Indien. Tranquebar, Serampore og Nicobarerne'. Gads Forlag (2017)