An article from Polarfronten

The Greenland shark: an overlooked creature

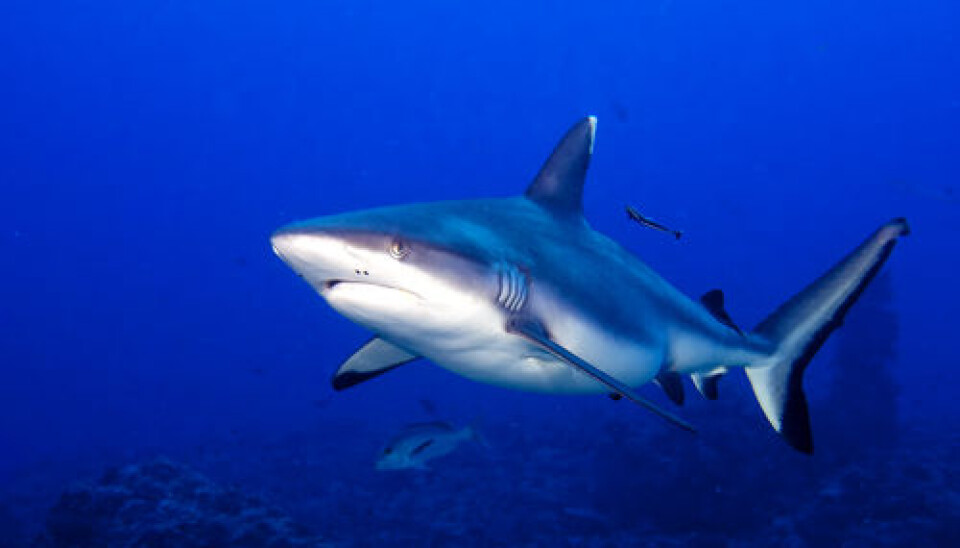

The Greenland shark is a mythicised and unpopular animal, perhaps due to a lack of knowledge. Now a research team has spent several weeks with some of Disko Bay’s Greenland sharks, where they performed risky experiments to find out more about the shark.

When Richard Martin, underwater photographer of National Aquarium Denmark, Den Blå Planet, recently found himself next to a Greenland shark in the algae-green waters of Disko Bay, he was surprised at how unthreatened he felt.

“One of my Greenlandic friends told me they have found both polar bear and seal remains in Greenland shark’s stomachs.

But I didn’t feel threatened now, even though I was directly beside them taking photos. The sharks we captured were very dull.”

John Fleng Steffenson, a biologist from the Marine Biology Laboratory at the University of Copenhagen, along with PhD student Julius Nielsen, have been trying to increase, the often overlooked, Greenland shark’s visibility.

Steffensen is familiar with this kind of lethargy in the sharks. He has encountered it in all the Greenland sharks he has helped catch. He and Nielsen concur:

“When we catch them, we have no trouble wrapping a line over the tail of a healthy, 300 kilo shark. It just lies listlessly in the water.”

A neglected but fascinating animal

In their spring expedition to Disko Bay, the biologists took biopsy samples and put ‘licence plates’ on 12 of the sharks.

Some sharks were equipped with satellite transmitters so researchers can eavesdrop on their swimming depths and migration patterns.

Beyond their sluggish behaviour, there are several things about the Greenland shark that fascinates the scientists and inspires them to spend weeks at sea.

“The immediate fascination lies in working with the world’s second-largest carnivorous shark,” says Nielsen.

The biologists are trying to answer a few basic questions: How big is their range, and what migration patterns do they follow? How big is their influence on their prey, and can they even catch live seals and fast-moving fish, or are these eaten as carrion from the ocean floor?

“These questions are important to better understand what kind of animal the Greenland shark is, and what role it plays in the ecosystem,” says Nielsen.

Biologists suspect that there may be several populations of Greenland sharks. Some populations stay firm in relatively smaller areas, while others may be highly mobile and move over large distances in a short time.

Changing opinions about the “local pest”

Greenland sharks were hunted from the 1700s until the mid-20th century, and were used for their high-fat liver oil to fuel oil lamps and as machine oil.

The Greenlanders’ relationship to the shark is strained. Fishermen who fish halibut and cod complain that the shark is a nuisance, which swallows hooks and eats the fish.

Nielsen adds, “In Greenland, the shark is considered to be a pest, but that opinion may change from a biology-standpoint. Since sharks are most likely to catch their prey alive, they can be an essential part of the natural selection process in fish and seal populations, and therefore probably ultimately helps keep their populations of prey healthy.”

---------

Read the original story in Danish

Translated by: Zöe Robertson