Remote corner of Greenland mapped in 3D

GREENLAND: Geologists have mapped a remote corner of northern Greenland in 3D for the first time and discovered new information about events that happened millions of years ago.

Eastern North Greenland was first explored a little over 100 years ago. But Kilen, a small 40 by 10 kilometre area surrounded by ice and water, was not studied in detail before the 1980s.

Since then the area has been little visited until a few years ago, when a small team of geologists from the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS) mapped this overlooked corner of the world- and I was one of them.

My job as a PhD student was to map the geology of the area in detail, using a brand new 3D-workflow.

From this we uncovered some of the geological secrets of the region--including, what happened when Greenland and Norway drifted apart as the North Atlantic Ocean opened up.

See some of the pictures from the trip in the gallery at the top of this article.

3D mapping with a normal camera

On reaching Station Nord, one of the northernmost manned bases in the world, we gathered our equipment and set about mapping this fascinating Arctic landscape.

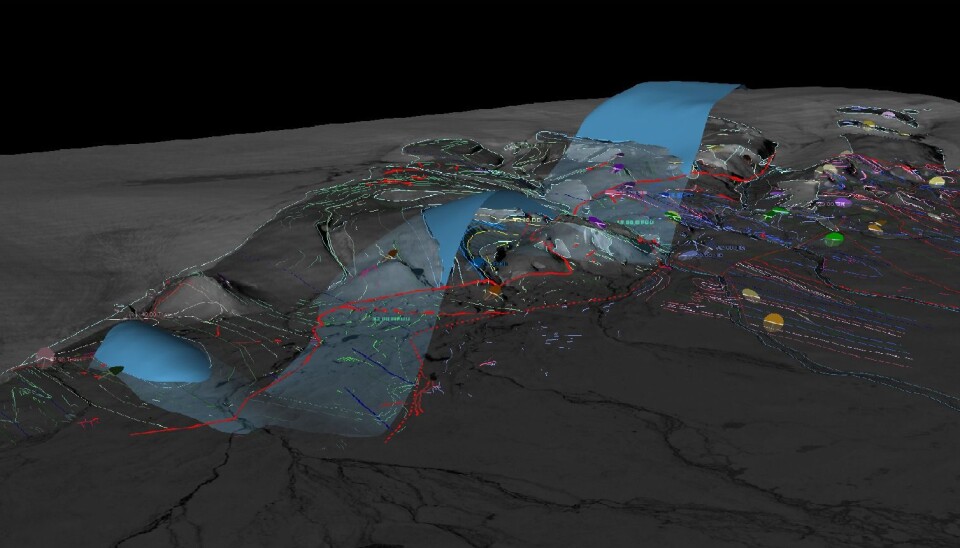

The new 3D-workflow involves flying over the area to be mapped in a helicopter and taking overlapping pictures out the window with a regular camera equipped with a GPS.

Safe at home in Copenhagen, I can combine these overlapping images on a computer to produce 3D-images. From here we can map the visible geological layers and build a 3D geological model that can help unravel the geological evolution of the area. The results of the 3D-modelling were verified with data collected on the ground by other members of the team.

Read more: 3D technology allows scientists to model Greenland's past

Phenomenal pressure as Norway and Greenland collided

The new mapping and 3D-modelling revealed geological layers of rock that had folded like a blanket due to tectonic pressure, sometime after the Cretaceous period.

This supports the theory that Svalbard collided with northern Greenland before they finally drifted apart, 35 million years ago when the North Atlantic Ocean opened up.

Our results from Kilen have answered several scientific questions but raise even more and so a new expedition is planned to Kilen this summer.

The objective of this expedition is to map rocks covering geological periods that were previously undocumented in this area of Greenland and areas along the margin of the ice sheet that have recently been revealed by retreating ice.

In some areas, the ice sheet has retreated by as much as one kilometre since the 1980s. It is a disturbing signal of a changing climate, but exciting for us geologists who now have access to these previously unknown geological layers.

-------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex