'Stay away from Allan, or you die'

A new research project examines threatening messages as a genre and the linguistic features characteristic of different types of threats.

In recent years we have seen an increase in threatening messages, not least through social media like Facebook, Twitter, and Snapchat. Interestingly, the number of hand-written threats has remained stable. This indicates that the motivations for writing threatening messages are quite diverse. Roughly speaking, hand-written threats occur more often in cases where writer and recipient know each other personally, whereas threats posted on social media are typically aimed at people unrelated to the writer.

But what does it take for something to be perceived as a threat? What linguistic aspects characterise threatening messages?

A new research project at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, aims to answer these questions by studying threatening messages as a genre and the linguistic particulars that distinguish different types of threats.

Indirect and direct threats

When the American President Donald Trump tweets that his red button is bigger than Kim Jong-Un’s, and when a frustrated father writes to a caseworker "Die! You will die! I will hunt you to the moon (…) I will flay you like a fish," we are dealing with two types of threats.

One of them indirect (albeit easily recognised), the other direct. Both seem to have been written in passion. Of course, we cannot know what the writers felt as they typed their messages but certain factors indicate that the texts are not the product of careful deliberation. This holds for factors in the context as well as the linguistic content itself.

A threatening letter left for a car owner who had parked in the writer’s regular spot. Click on the red (i) to see the translated text. (Photo: Engelhardt & Lund 2008)

Trump’s threat is grandstanding

Let us examine Trump’s threat first.

We already know that the 45th president reacts spontaneously, has a flaring temper, and frequently changes position on policy.

North Korean Leader Kim Jong Un just stated that the “Nuclear Button is on his desk at all times.” Will someone from his depleted and food starved regime please inform him that I too have a Nuclear Button, but it is a much bigger & more powerful one than his, and my Button works!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 3, 2018

In addition, Trump explicitly writes in this tweet that Kim Jong Un ’just’ referred to his nuclear button and then proceeds to the completely needless proclamation that his own, bigger and more powerful button, works.

This last part invites the inference that the North Korean button doesn’t work, a supposition that seems baseless given the nuclear tests that the North Korean regime have already conducted. Rather than an actual threat to be taken seriously, these factors point to grandstanding (much like school yard comebacks of the type ’my dad is stronger than your dad’).

The father’s threats contain absurd declarations

On to the case of the frustrated father.

According to media reports, the tweet was sent by a father who had been involuntarily separated from his children for a longer period of time. Due to an unacknowledged substance abuse he was denied access to his son on his birthday.

Prompted by this, he sent several threatening messages to caseworkers and staff at his children’s care home. Linguistically, the messages contain quite violent phrases but at the same time they are almost poetic in their absurd portrayals of an imagined chain of events (“I will hunt you to the moon”) and in their imagery (the simile and alliteration ”I will flay you like a fish”). These features make them no less frightening to their recipients, we hasten to add.

Presumably, this threatening letter was sent by a biker gang who demanded that their stolen goods be returned. Click on the red (i) to see the translated text. (Photo: Engelhardt & Lund 2008)

Threats as extortion

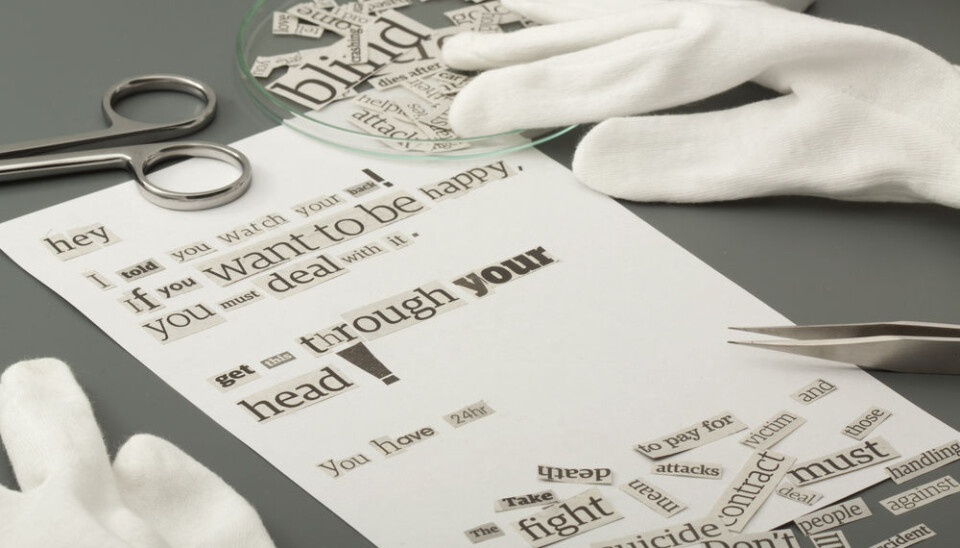

A third type is the conditional threat. Conditional threats follow the basic template of ‘if not x, then y’. The condition typically designates an action that the recipient is supposed to perform, and thereby the message turns into an extortion.

Obviously, the purpose may be to achieve a financial gain but as exemplified below, the objectives can vary a great deal (for instance the return of stolen goods, silencing the recipient, outmaneuvering a romantic rival and so on).

The following examples are all translated from Danish and were originally published in Engelhardt & Lund (2008) and 2009. Spelling mistakes from the original have been corrected in the translation:

- "We feel sorry for you since your life will change totally after 1 February if you do not pay what you owe."

- "You have 48 hours to place it outside his door or else a big horde of supporters will come and visit you."

- "You mean nothing to us and we will naturally direct the attack against you, but in order for you to realise the seriousness of this message we have chosen to include your family so you can understand the seriousness and what consequences it may have for your family if you do not immediately follow our instructions."

- "STAY AWAY FROM ALLAN / OR YOU WILL DIE / I MEAN IT / HE IS MINE and / ONLY MINE / GET IT."

The decisive factor – what makes it a threat – is the sanction that follows if the recipient does not perform the requested action. What this sanction amounts to can be explicitly stated or kept deliberately vague (but still with considerable potential for producing concern or fear in the recipient).

In messages where the sanction is not mentioned at all, contextual information is often required to determine whether it constitutes a threat or not.

Threatening letters from a neglected lover. Such threats are written by women just as often as by men. Click on the red (i) to see the translated text. (Photo: Engelhardt & Lund 2008)

Merely a warning or an actual threat?

An underlying ambiguity and indirectness is characteristic of many threatening messages. There are several reasons for this.

First of all, the hidden and unknown are causes of anxiety and by alluding to these the perpetrator has already attained one important objective with their message, namely to frighten the victim.

Secondly, it is illegal to threaten someone’s life, health, or property and the perpetrator therefore covers himself by using ambiguities and vagueness.

If the message can be interpreted as a warning instead of a threat the perpetrator can simply deny that it was ever meant as a threat and hope therefore to avoid prosecution and conviction (this is sometimes referred to as 'plausible deniability').

Do threats in Danish resemble those in English?

Luckily, only a minor part of all threats are realised according to American research into threatening messages.

The data set that we have collected so far allows us to study whether this holds true for Danish as well, since none of the threats were ever carried out. Obviously, it would be ideal to compare such threats with ones that were realised since that might point to linguistic indicators of a heightened threat level. This could improve threat assessment for authorities and organisations that perform such tasks.

However, realised threats are much more difficult to gain access to because they are investigated and charged under more severe sections of the law.

Our project constitutes basic, scientific research but it has other potential applications beyond threat assessment. For example, a fully annotated database of threatening messages could assist police investigators in establishing patterns or links between new threats and those contained in the database. In Germany, criminal cases investigated by the Bundeskriminalamt have been linked solely on the basis of linguistic similarities (pers. comm.).

---------------

Read this article in Danish at ForskerZonen, part of Videnskab.dk

How can you get involved in our research?

We need as large datasets as possible for our research and would be grateful if you as readers contribute to our data collection.

If you have received or come across a written threat (whether on social media or not) we hope that you will take a picture or a screen-dump of it and send it to tekstbase@hum.ku.dk.

We do not perform criminal investigations of submitted threats but will incorporate them in our collection so we can study their linguistic and generic features.

Translated by: Tanya Karoli Christensen and Marie Bojsen-Møller

Scientific links

- 'Threatening Stances: A corpus analysis of realized vs. non-realized threats', Tammy Gales, Hofstra University

- 'Jeg er bevæbnet and har tømmermænd', Engelhardt & Lund 2008

- 'Jeg tager bomben med, når jeg går', Engelhardt & Lund 2009