There are 8,475 languages that we know of

What do we know about the new languages that are appearing and how does a new language form? Researchers from Aarhus University, Denmark, are investigating just this.

In Italy they speak Italian. In Germany they speak German, and in Denmark, Danish. If this was true for all other countries, there would be 193 languages spoken today.

But in reality, there are many more: 8,475 according to glottolog.org, where linguists map languages from around the world.

In fact few countries speak just one or two languages natively, such as Iceland and Denmark. Besides their mother tongue, most people there also speak English.

And if that was not confusing enough, new languages are being developed all the time. For example, so-called creole languages, which arise when two or more groups of people all with their own languages come in contact with each other, and need to communicate.

In our research group at Aarhus University, Denmark, we compared these newly developed grammars with non-creole languages from around the world.

The results were spectacular.

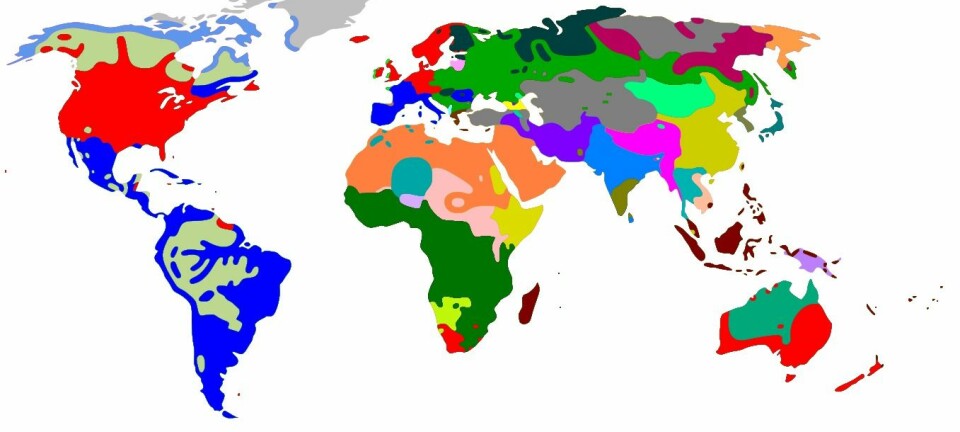

A diversity of languages around the world

Even though many of us speak just one or perhaps two languages, in ten countries around the world there are more than 200 spoken languages, including Cameroun, Nigeria, USA (including Native American languages), and Indonesia.

Papua New Guinea is the current record holder for the number of spoken languages. With a population of eight million, a little more than that of Denmark or Scotland, they speak no fewer than 800 languages! And they are all very different.

Some languages sound very similar, have similar words, and stem from the same proto-language, where dialects have developed into different languages.

Linguists refer to related languages as coming from the same linguistic family. For example, Danish belongs to the Indo-European family, just like almost all languages spoken between Ireland and Bengal, including Armenian in the Black Sea region and Urdu in Pakistan.

Any language can be viewed as a tool that we humans use to talk about anything in the Universe and fictional worlds.

Some languages have no numerals or adjectives, others have 30 ways of forming a plural and others have none at all. Some have 15,000 different verb tenses and others have no tenses. And some languages have just 10 different sounds (Pirahã in the Amazon), while others have 112 (Taa and !Xóõ in Southern Africa).

But this incredible diversity of languages is far from static.

Read More: Evolutionary biology can help us understand how language works

Linguists fear language death

Linguists are pessimistic about the prospect of maintaining the current diversity of languages.

People chose to speak a language that gives better job prospects, and forget that this does not mean they have to say farewell to other languages spoken by their parents.

Some researchers estimate that just 10 per cent of the world’s languages will survive this century.

An average language is spoken by somewhere between 3,000 and 5,000 people. So even a language like Danish with five million speakers is actually one of the world’s biggest languages--larger than 90 per cent of all other world languages.

While many languages die out, new languages also emerge. And seeing how these new languages have originated over the past 500 years opens a fascinating window on people’s cognitive abilities.

Tok Pisin is a creole language spoken in the northern Papua New Guinea.

Creole language: The newborn of languages

When two or more groups of people with different languages come into contact with each other, the resulting language is called a creole when people start speaking it as their mother tongue or a default language in the community.

Such a situation has occurred many times and there are perhaps 100 known creole languages.

It typically starts among adults who do not share a common tongue, such as soldiers, traders, workers, students, or slaves. Some of them can be relatively powerful people, such as plantation owners, slave traders, or army commanders, who exert more influence than others. And everyone else learns their vocabulary.

In these situations, no authority tells people how to conjugate their verbs. Their need to communicate with each other outweighs the desire to learn to speak each other’s language correctly. Instead, they create a new one that is easier to pick up using the language of the most powerful group as a basis.

Read More: What is the world’s weirdest language?

The recipe for creole

The recipe to create a new creole language is logical and simple. It is pretty easy to learn words, but it’s not so easy to learn grammar and various conjugations, clauses, grammatical genders, and irregular rules. So you just forget about them.

For example, you can imagine a worker who needs to explain to his or her colleague that he is going to start work on the plantation soon. He has learnt a little English, but he cannot say “I will go and work on the plantation.”

Instead, he can say “by-and-by me go work plantation.” He uses the vocabulary from the boss whose language everyone knows to a limited extent, but not the correct grammar, and often redundant peculiarities like gender, clauses, and other complicated parts of the language. This is what occurred with English in Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea in the Pacific Ocean.

First, you develop a simplified pattern of communication, where you prioritise prominent and emphatic words—those that are emphasised by the leader or boss. So instead of “will”, you might say “by-and-by” to indicate that something is happening in the future. Instead of “I” you use the more emphatic “me.” Prepositions, such as “at” or “the” can be dropped. And perhaps over time this evolves to “mi ba-wok planteshen.”

All the words come from English, but the grammar is new. “By-and-by” has turned into “ba,” and is placed close to the verb.

Other examples from Scandinavia

Here are two other examples from Scandinavia.

A pidgin called Russenorsk developed in northern Norway during the 17th century. In this contact language you might use the Russian moja “my” to mean “me,” instead of the Norwegian jeg “I” or the Russian word pian meaning “to drink” , which in Norwegian is drikke.

But Russian-Norwegian never developed into a full creole language.

Another example developed in 16th century Danish West Indies, where Danish replaced certain Dutch words to form a Dutch-based creole language known as Die Creol taal.

Read More: Fight on to preserve Elfdalian, Sweden's lost forest language

Creole languages are unique

In our research, we have compared creole languages with a large selection of non-creole languages for which we were able to collect data.

Looking at multiple combinations of creole and non-creole languages, we can see that there is always a small space where (almost) all creole languages are found, and no non-creole languages.

We have used databases with thousands of data on grammatical trends of hundreds of languages, and we never see an overlap of traits, where creole languages cluster with non-creoles.

We have looked at Arabic-based, Dutch-based, French-based, Spanish-based, and Portuguese-based creoles, as well as their dialects and colonial variants.

In every case, creole is distinct to the non-creole. This surprised us, as we had expected to see overlap between languages from Africa and Asia that superficially resembled creole.

In Germany, linguists have done the same exercise for English creole, and their results agree. We have also compared creoles with non-creoles that similarly do not use verb conjugations, cases or grammatical genders, and still, the creole languages are distinct.

Does the human brain use universal grammar?

Some argue that creole is structurally influenced by African languages, associated with slaves.

There are clear influences from these languages. But when you look at many traits simultaneously the impact from Africa is surprisingly small, even though quite a few of them are spoken by people of African origin. Creole languages created by people from Africa more closely resemble other creole languages in Asia than the African languages spoken by these enslaved people.

This similarity across different types of creole all over the world suggests that people all around the world use the same cognitive skills when they create a new grammatical system.

And this is a fascinating thought.

Our research has revealed that a language can be described as a creole if it meets these conditions:

- It has a verb for “to have” (only 25 per cent of languages have this)

- It has an indefinite article “a” that equates to the number one (40 per cent of the world’s languages have this)

- It does not have any verb tenses (for example, there is no formal distinction between “I buy” or “I bought”)

- It does not have a separate word for “not” (about half of all world languages have this)

None of these traits are rare, but only in creole languages do we find all of them together. Many are found in European languages.

Clearly, people build new languages in the same way in Africa as they do in Asia, America, and Australia, even though the vocabulary comes from different source languages.

---------------

Read this article in Danish at ForskerZonen, part of Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex

Scientific links

- 'Creole Studies: Phylogenetic Approaches.' Bakker, Peter et al., John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2017

- 'The morphosyntax of varieties of English worldwide: A quantitative perspective', Szmrecsanyi, Benedikt, Kortmann, Bernd, Lingua, 2009. DOI: 10.1016/j.lingua.2007.09.016