Taste can improve cancer patients’ quality of life

Chemotherapy patients often lack the ability to taste food during and after treatment. A chef and a team of scientists aim to change this and boost patients’ quality of life.

One of the big challenges for cancer patients during and after chemotherapy is the loss of taste and desire to eat.

This puts chemotherapy patients at further risk because they cannot eat enough.

It also impairs their quality of life for both patients and their relatives who struggle to create dishes that the patient wants to eat.

Many patients experience changes to their ability to taste food and this can have big consequences for their food intake. Patients have described how favourite dishes suddenly taste metallic.

In the end many patients simply do not want to eat.

“Taste for Life” and the good life

In “Taste for Life” we work with taste as a driving force for both nutrition and a better quality of life.

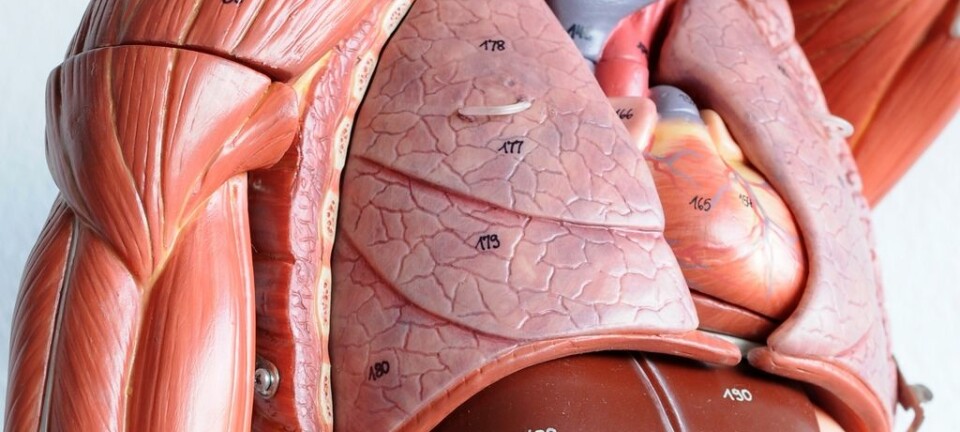

A taste experience is a multisensory event, which does not only include the five senses of sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell—it also includes our brain via memories and emotions.

We say that taste is in the brain and is influenced by our surroundings, memories, social relationships and earlier experiences and therefore also involves sensory physiology and neurology.

Our experiences in researching and communicating taste, combined with practical cooking experience and scientific insight into what gives food its taste and “mouthfeel,” can be used to offer cancer patients a better eating experience and quality of life after their treatment.

Pilot project under-way

We have applied our experiences in the Taste for Life project to a pilot project, which aims to stimulate patients’ appetites and their desire to eat.

The project took place in four stages and with four groups of cancer patients who had finished chemotherapy treatment and were either based at home or had gone back to work.

Included in the groups were 1) 15 to 20 young cancer patients under the age of 30; 2) a mixed group of young and older cancer patients; 3) a group of doctors, psychologists, people from cancer support groups, and patients who teach voluntarily; 4) and a fourth group of mixed cancer patients.

The starting assumption is that patients are often alone or not in work and they have a range of psychological problems that accompanies their disease and treatment. Often, they do not have anyone to care for them.

Moreover, they find their prescribed diet boring, which can lead to a sense of hostility between the patient and their councillor from both the hospital and the cancer support groups.

The patients are often knowledgeable from reading online and think that the doctors say one thing, while the councillors say another.

Central to this advice is the food pyramid, and patients may be required to avoid certain foods.

Spicy cucumber and caramel tomatoes

Chef Klavs Styrbæk takes a different approach.

Together with the group of patients, he starts by looking into the dining experience and what makes for a good experience, what tastes are, and he serves tasting samples along the way.

He plays with taste, for example by serving small crispy tomatoes with a caramel taste, or cucumbers infused with other flavours and spices.

The idea is to find ways to compensate for the reduced sense of taste that accompanies chemotherapy and therefore it is important to play around with the other senses.

Variation in taste is a key concept and everyone is invited into the kitchen to follow along with the preparation and talk about the raw ingredients and focus on basic techniques. Simplicity is preferred over complexity.

New appetites for patients

The results of the pilot project are anecdotal, but promising.

Patients who would once throw up at the sight of food no longer do so.

Even the most sceptical participant in one of the groups reported that she had gained a “new life,” that she had forgotten about the other senses than taste, and that she can now taste “creamy, sour, sweet, and burned.”

---------------------

Read the full story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex