Fatty liver is the new threat to national health

A Danish scientist is scrutinising millions of Danish and American genes, looking for an explanation to why increasing number of people are afflicted with fatty liver.

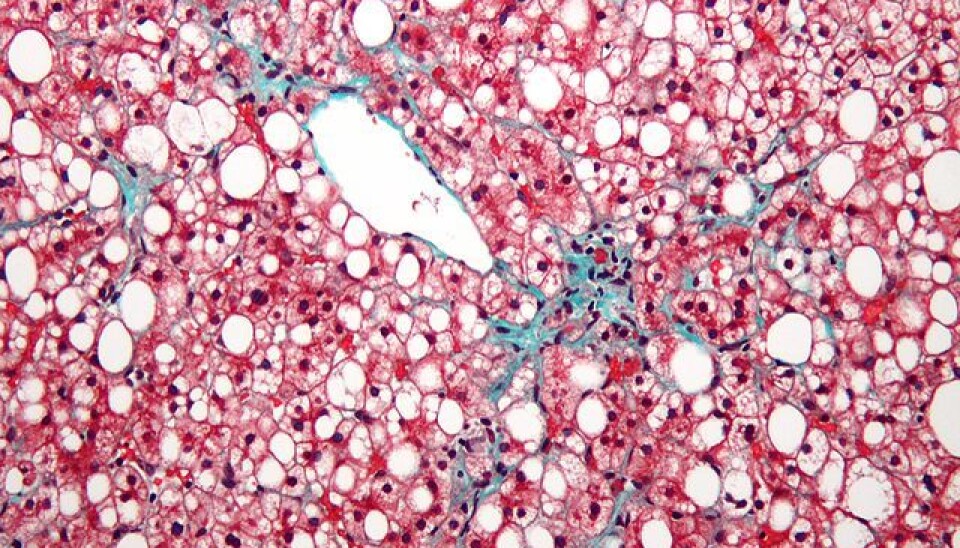

If you think only alcoholics get fatty liver disease, think again: in recent decades an increasing number of people have been experiencing serious liver problems, despite not drinking more than what is recommended.

As much as one third of all Americans have too much fat in their livers.

If a person is obese and inactive, there is a risk that their liver will be smothered in fat. Moreover, studies indicate that the tendency towards fatty liver can also be hereditary. Because of this, one Danish scientist is currently looking for the genetic factors that increase the risk of developing the disease.

“Over the course of the past few decades, fatty liver, triggered by other factors than alcohol, has become extremely common in the Western world. It’s likely that genes account for as much as 25 to 50 percent of a person’s risk of developing the disease. We’re examining whether certain differences in the DNA are more common in people with fatty liver than in others,” says Dr. Stefan Stender, who has received a grant from the Danish Council for Independent Research for his study.

Method revolutionised medical science

Stender will do the gene analyses at the University of Texas in the US, where he and his colleagues are examining millions of genes from 130,000 Danes and. Using a special chip, the scientists will measure a total of 250,000 different places in the genomes of all participants. The aim is to find DNA variations that are prominent in patients suffering from fatty liver disease.

The method, which is known as the Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWA), has revolutionised science in recent years: using the microscopic chip, scientists have already identified genes that are involved in a number of diseases and ailments, from allergies to schizophrenia.

“The chip is added to the DNA of each study participant, where it can measure 250,000 places in the genome that typically vary from person to person,” says Stender.

“The research group that I’m working with is among the world’s leading in the field of fatty liver research. They have employed a very exact method to measure liver fat in 3,000 people from Dallas. These 3,000 measurements are used to discover connections between genes, lifestyle, and fatty liver disease,” he says.

More methods brought into play

Stender collaborates with the Danish population studies “The Copenhagen City Heart Study” and the “Copenhagen General Population Study”. The studies, which follow the health of 100,000 Danes over an extended period of time, is one of the alargest in the world.

Analysing the DNA from a large number of participants in the extensive population studies and comparing the results with analyses of DNA from more than 3,000 Americans allows Stender and his colleagues to determine whether there are variations in the genome that increase or decrease the risk of developing fatter liver disease.

“In addition to the GWA method, which we use to measure areas of the genome where DNA differences are commonly found, we use another method, called exome sequencing, to measure all genetic variations, both rare and common, in a subgroup of the participants,” says Stender.

Exome-sequencing is much more extensive and costly than GWA, for which reason the method is not used on all of the 100,000 participants in the study.

Scientists examine entire DNA

The advantage of exome-sequencing is that the scientists can map all genes in a person’s genome with a single sample. The genes are the part of the DNA that codes for proteins.

The proteins control and take part in nearly all of the organism’s processes, as they act as a connecting link between the genes and their properties. This means that they control our genetically determined risk of developing certain illnesses.

“Once we have mapped the entire genome, we examine whether there are certain genetic variations that are associated with the amount of fat in the liver. One benefit of the two methods we use is that we look through the entire DNA without having any biased assumptions about where we will find the differences and genetic variations that can increase the risk of fatty liver,” says Stender.

However, he stresses that even though he and his colleagues find genetic factors that may increase the risk of accumulating too much fat in the liver, it is far from certain that the bearer of the genetic variations in question will develop fatty liver.

“The overall risk depends on the interplay between genes, lifestyle and environment. The risk of fatty liver can be reduced significantly by avoiding getting overweight. It is likely that regular exercise can also inhibit accumulation of fat in the liver,” he says.

Stender hopes the results of the study can eventually be used to develop a drug that targets the genes that increase the risk of fatty liver.

--------------

Read the original story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Iben Gøtzsche Thiele

Scientific links

- 'Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease'. Nature Genetics 2008. DOI: 10.1038/ng.257

- 'Exome-wide association study identifies a TM6SF2 variant that confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease'. Nature Genetics 2014. DOI:10.1038/ng.2901