Uncertainty worse than torture in developing country prisons

Prisoners everywhere can become depressed, aggressive or anxious because they feel incapacitated. The feeling of powerlessness can be the hardest one to deal with – even for inmates who are tortured and sit in crowded cells, new research shows.

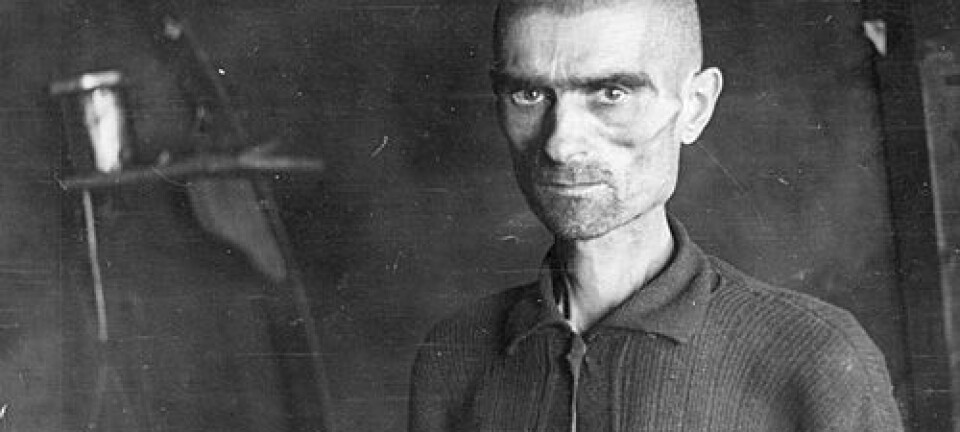

Inmates sleep standing up because the prisons are overcrowded in one of the world’s poorest countries, Sierra Leone. Many of the inmates have to wait for years to get a verdict.

In the Philippines, it can also take years before the prisoners are brought before a court. Many of them are tortured during interrogation, but end up being acquitted once their case is tried.

“They are slapped on the ears and hit with iron pipes elsewhere on the body. There is also a practice in which they are covered in oils with strong spices, even on the genitals,” says Liv Gaborit, a research assistant at DIGNITY – the Danish Institute Against Torture.

”The torture usually takes place during interrogations to get them to confess or inform against their friends.”

Gaborit has interviewed political prisoners and observed daily life in Philippine prisons, where many of the inmates wait for years to have their case tried in court. The ethnographic fieldwork is part of DIGNITY’s research project ’Understanding Prison Reform – a study of entangled practices in Sierra Leone, Kosovo and the Philippines’.

Daily stress overshadows torture

When Gaborit interviewed the Philippine inmates, they rarely spoke of the torture. Instead, it was the waiting and the uncertainty that characterised their conversations about prison life.

“In prison they focus on survival. There is no torture that they have not been exposed to, but it is the daily problems that they focus on,” she says.

“The Philippines are a country in which many people are exposed to traumatic events such as typhoons, shooting episodes and violence. They experience harsh things and learn to live with it.”

They are slapped on the ears and hit with iron pipes elsewhere on the body. There is also a practice in which they are covered in oils with strong spices, even on the genitals.

Even though many of the Philippine inmates have symptoms of posttraumatic stress as a result of the interrogation torture, they do not focus on the psychological scars while they are in jail. In the cells, they have other problems to think about:

“They said they had emotional problems, but not in relation to torture. It was the stress of being in prison and far away from the family that filled their daily lives. They felt incapacitated if the family on the outside had problems that they couldn’t handle,” explains Gaborit.

Objectifying prisons

When people are treated as objects that have no control over their daily lives, they often end up feeling incapacitated. The quality of life drops significantly because, according to psychological research, when people are unable to act as independent individuals, their personal development grinds to a halt.

On the Philippines, the depression, aggression, anxiety or psychosis that can arise when people are objectified and are stripped of the power to act is described with the word ‘buryong’.

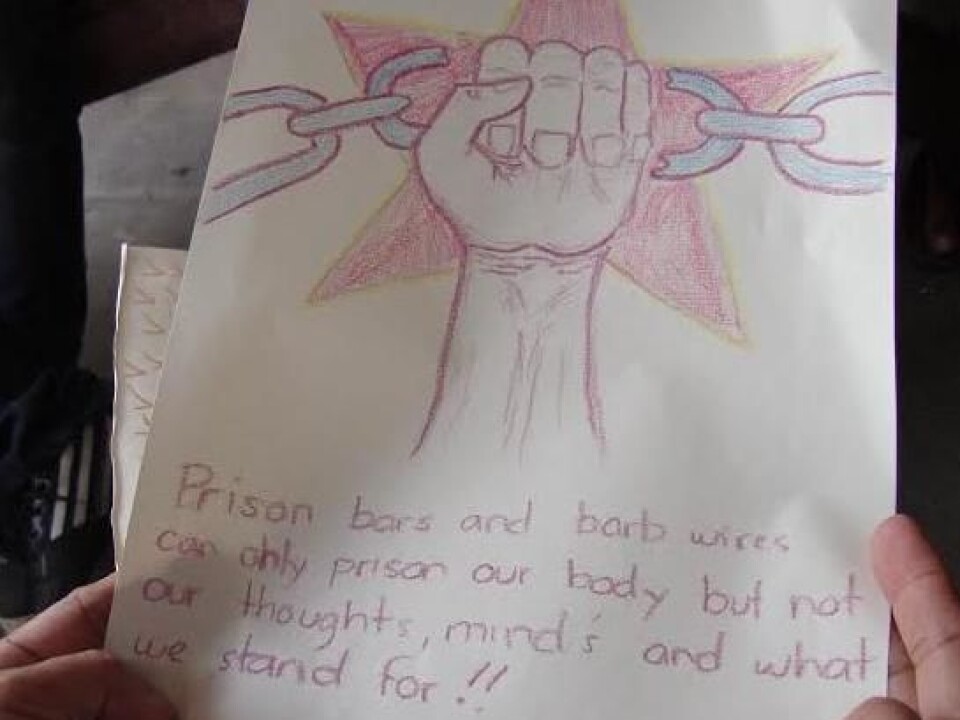

Politics and religion give meaning to prison life

In prison they focus on survival. There is no torture that they have not been exposed to, but it is the daily problems that they focus on.

Gaborit’s studies show that inmates in the overcrowded Philippine prison have different strategies for dealing with the feeling of ‘buryong’.

The inmates she interviewed are political prisoners accused of having engaged in violent guerrilla insurgency, and Muslims, who were also accused of having fought the regime without having obtained a verdict.

It appears that both groups of prisoners manage to survive emotionally because despite the lack of freedom they do have the opportunity to be part of a community with like-minded people.

Political prisoners: ”The left-oriented inmates continue their revolutionary struggle in prison. Having a case to fight for and a sense of belonging makes it easier for them to cope with prison life, the powerlessness and the uncertainty of how long they have to wait,” says the researcher.

If you cannot pay, you end up in prison. Those who are incarcerated often don’t know what they are accused of, and if they have been sentenced, they don’t know when they will get out again.

Religious prisoners: The interviews revealed that the Muslims find meaning in prison life by devoting themselves to their religion and regarding the horrors of prison life as the will of Allah.

”Common to both types of prisoners is that they appear to be able to handle the feeling of ‘buryong’ without breaking down, because they have the opportunity to interact with others who have the same conviction as they do and form groups.”

Prisoners sleep standing up

In one of the world’s poorest countries, Sierra Leone, which is still recovering from a bloody ten-year civil war that ended in 2002, the prisons are even more overcrowded and disorganised than in the Philippines.

Many of the inmates in the country’s prisons are poor people from slum areas. Some of them have been in the wrong place at the wrong time and could not afford to pay themselves out of jail.

”If you cannot pay, you end up in prison. Those who are incarcerated often don’t know what they are accused of, and if they have been sentenced, they don’t know when they will get out again,” says Andrew Jefferson, who heads DIGNITY’s ’Understanding Prison Reform’ project.

”Many of them worry that their families do not know where they are because they haven’t had the chance to tell them that they are in prison.”

Slums are similar to prisons

A few years ago, Jefferson interviewed inmates in a Sierra Leone prison that was so cramped that some inmates had to sleep while standing up.

As in the Philippines, the uncertainty and the powerlessness were reported as the worst part of being in prison.

Seen from a European perspective, the prison conditions are inhumane; however, the conditions were not that much different from the living conditions that many of the Sierra Leonean inmates grew up with, says Jefferson:

“You could compare the slum areas that many of them come from to prisons. In the slums, people also lose the power to act because they have no control over their own living conditions. They are forced to live close to people they have not themselves chosen to live with, and there are no opportunities for scraping money together so they can leave.”

Andrew Jefferson and Liv Gaborit are contributing to a research-based book, which is scheduled for publication in 2015. The book will be about the encounter between human rights organisations, prison authorities and inmates in Sierra Leone, the Philippines and Kosovo.

-----------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk