Researchers' Zone:

When epidemics change the world: Can we learn anything from the third plague pandemic?

Around the year 1900, the third plague pandemic raged. This paved the way for several major changes in society and interacted with developments that were already underway. Perhaps this will also be the case with the present crisis, a history researcher writes.

Right now, social scientists are busy guessing what the corona crisis will mean in the long term.

The questions are many and do not only concern health.

Is the fragmented U.S. health care system going to survive?

Does the corona crisis expose the vacuity of vociferous populists like Trump in the United States and Bolsonaro in Brazil, or are the 'strong men' rather growing in strength?

Is the crisis-hit social-democratic welfare state going to experience a renewal? Has the crisis given Denmark its strongest prime minister in decades?

Only time will tell.

The third plague pandemic

In the meantime, we might become a little wiser if we take a trip around the world in the years around 1900. This is a couple of decades prior to the 1918 pandemic flu; nonetheless, the plague was ravaging – yet again.

Just as it is rare, fortunately, for a new virus to leap from animals and infect humans to the extent that COVID-19 has, a plague epidemic also requires a special process in which fleas from rats infected with the plague bacterium are forced to seek new hosts, including humans.

This happened in Southern China and Hong Kong in 1894, thus initiating the third plague pandemic.

It is not particularly well known. To most people, ‘the plague' equals the Black Death of the Middle Ages. The former’s relatively unknown status is due to the fact that it was by far the most severe in the global south, where it claimed some 15 million victims.

In Europe, the victims could be counted in the thousands, and in the United States in the hundreds. The plague struck the poorest people; those who lived close together and close to rats. It was, therefore, entirely consistent with the very unequal world order of its time.

From Hong Kong's busy port, the plague spread via rats in the holds of cargo ships. Compared to the coronavirus that engulfed the world in a few months, the plague bacterium travelled slowly and spent years reaching the most remote destinations.

The risk of contracting the disease was not nearly as high as we are now experiencing with the current coronavirus; however, if one contracted the disease, the mortality rate was dramatic – up to around 80 percent.

Over-confident science was wrong about the infection

When the plague hit, Western scientific medicine was full of confidence.

By the 1880s, the bacteriological revolution led by Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur had identified the microorganisms that caused diseases such as cholera and tuberculosis.

It was not long before the plague bacterium had been identified, but much was still unknown in terms of how the plague was spread.

More than ten years were to elapse before it was discovered that the crucial carrier of the disease was flees from rats.

Until then, it was therefore assumed that the infection was transmitted directly from one human being to another, and, in many cases, this meant that unfortunate strategies were chosen in the battle against it.

The ‘International Sanitary Conference’ – a precursor to the present day WHO – recommended the isolation of infected people, disinfection or destruction of property and houses – and, to a certain extent, rat control.

Isolation was largely ineffective, since plague only transmits from one human being to another in cases of the rare pneumonic plague.

Disinfection and destruction could even be harmful because it caused the rats to flee and spread the infection. Only rat control made any sense.

Bombay - the plague and the nationalist movement

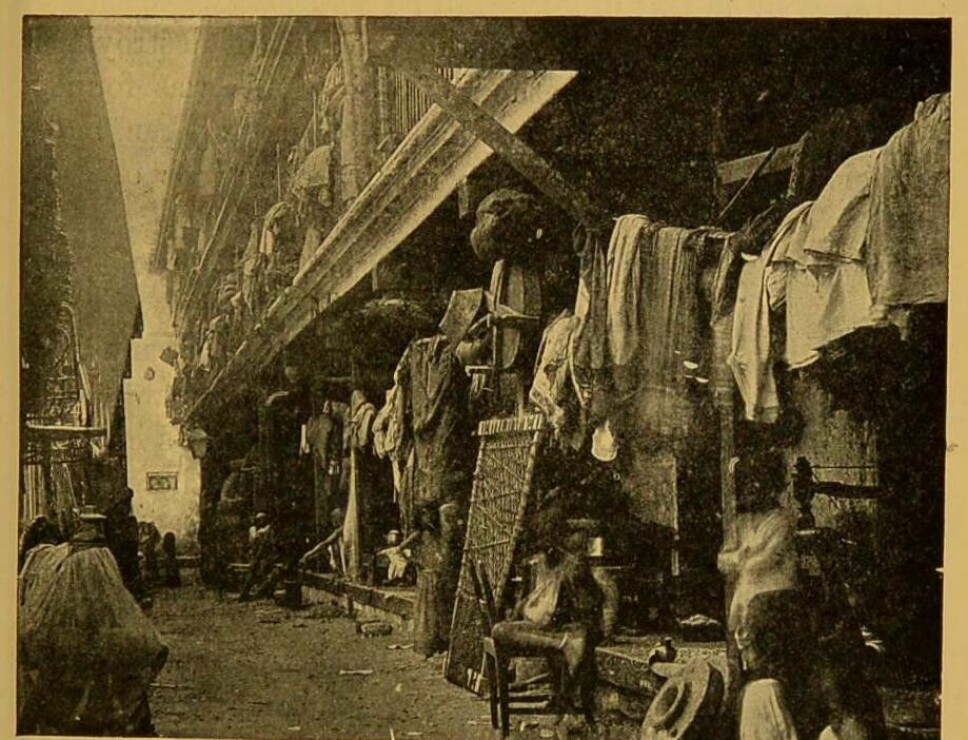

The plague arrived in Bombay (now Mumbai) on the west coast of India in 1896.

This was one of the worst places imaginable. Bombay was India's leading port and a hub in the British Empire.

The metropolis was therefore well connected with shipping routes across the oceans and railway lines into the Indian hinterland.

In addition, the city housed one of the world's largest concentrations of poor people with weakened immune systems in overpopulated and unsanitary slums.

Throughout the 19th century, the British colonial power had been reluctant to make health interventions in Indian society, but that was about to change.

Spurred on by the achievements of the bacteriological revolution, the belief that epidemics could actually be overcome increased. And when the plague arrived, they were ready to strike.

Intransigent Brits ignored Indian voices

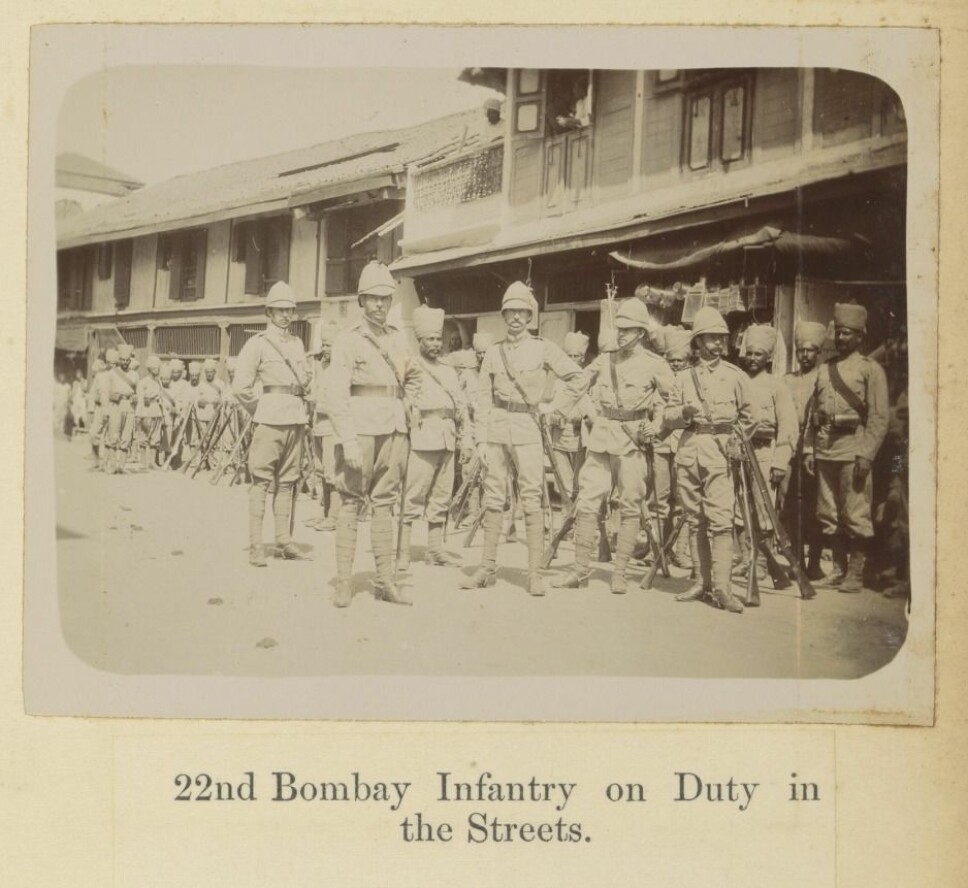

The British intervened with unprecedented ferocity. People were forced into hospitals and body searched without any kind of sensitivity, floors were torn up and houses torn down, while streets and sewers were overflowing in disinfectants.

The British administration had two problems. On the one hand, the violent interventions were largely futile and, on the other hand, the government enjoyed very limited levels of legitimacy in the population. The British were entirely insensitive to the conditions and feelings of the Indian population.

Extremely poor residents witnessed their few possessions go up in smoke, and, for many people, being admitted to a hospital was one of the worst things that could happen. As was also the case during the Ebola epidemic in West Africa in 2014-16, hospitals were considered places from which only corpses came out.

In addition, Western India was one of the focal points of the Indian nationalist movement, which demanded political influence. However, no Indian people were asked for their advice at the outbreak of the plague, and the occasion was even seized on to forbid festivals organised by the nationalist movement.

This was to be the recipe for violent confrontations. In Bombay, hospitals were attacked, but the most violent confrontations were in Pune (Poona), 100 kilometres inland. These confrontations claimed the lives of the particularly brutal plague commissioner and his escort.

12 million Indian deaths aided Indian independence

The riots caused the British to bow down. They placed more emphasis on voluntary initiatives to stop the plague and began collaborating with the leaders of the nationalist movement.

If the handling of the plague was a defeat for self-assured Western medicine and the authoritarian British Empire, it nonetheless strengthened the nationalist movement.

The plague outbreak in Bombay and Pune is today considered a significant event on India’s path to independence.

With the altered and subdued British policy, the worst confrontations with the Indian population were averted, but the plague initiatives remained ineffective.

The outbreak of the plague continued to spread in the following years to large parts of India, culminating in 1907, where the death toll reached more than one million.

Altogether, the third plague pandemic claimed around 12 million lives in India – it was a very Indian pandemic.

Cape Town - the plague paved the way for racial segregation

In 1901, the plague also arrived in Cape Town, South Africa. The scale was much more limited than in Bombay – 807 cases and 389 deaths – but here too the disease played an interesting role in a broader social dynamic.

The plague outbreak in Cape Town became a significant event in the development of racial segregation and apartheid in South Africa.

The plague arrived during the Boer War, and this meant that Cape Town was experiencing an influx of Africans.

At the same time, ideas were forming of physically segregating the area’s white, ‘coloured’ (Asians and people from the Middle East) and African populations.

The idea was political but fuelled by medical notions that Africans were dirty and disease-infested.

Although it was known that plague was caused by a bacterium, and that rats played a role in its spread, the African ‘race’ was used as a ‘scapegoat’ for the outbreak.

The measures that were put into place were especially aimed at the African population, while the white and coloured populations often walked free.

The plague was not more dangerous than smallpox - but effected many more changes

Measured on the number of deaths, the plague was not worse than the outbreaks of smallpox that often haunted Cape Town; and yet, it was considered a much greater danger.

Whereas smallpox only affected the poorly vaccinated coloured and African population, the plague could infect anyone.

And whereas smallpox outbreaks were considered a local problem, the plague was a threat to commercial interests in Cape Town because it triggered strict quarantine regulations for merchant ships.

The plague therefore called for drastic measures.

Racist compulsory evictions were made permanent

On March 12th, the authorities in Cape Town decided to evict practically all African inhabitants from the city by force to a sewage collection ground.

It was not possible to justify the forced eviction with concrete medical arguments but rather with an overarching, racist worldview.

Thus, in 1902, the ‘Native Reserve Location Act’ was passed, making temporary forced segregation permanent.

The plague outbreak not only served as a lever for racial segregation in South Africa, it also provided a model for future use.

During the great flu epidemic of 1918, history repeated itself (see here and here).

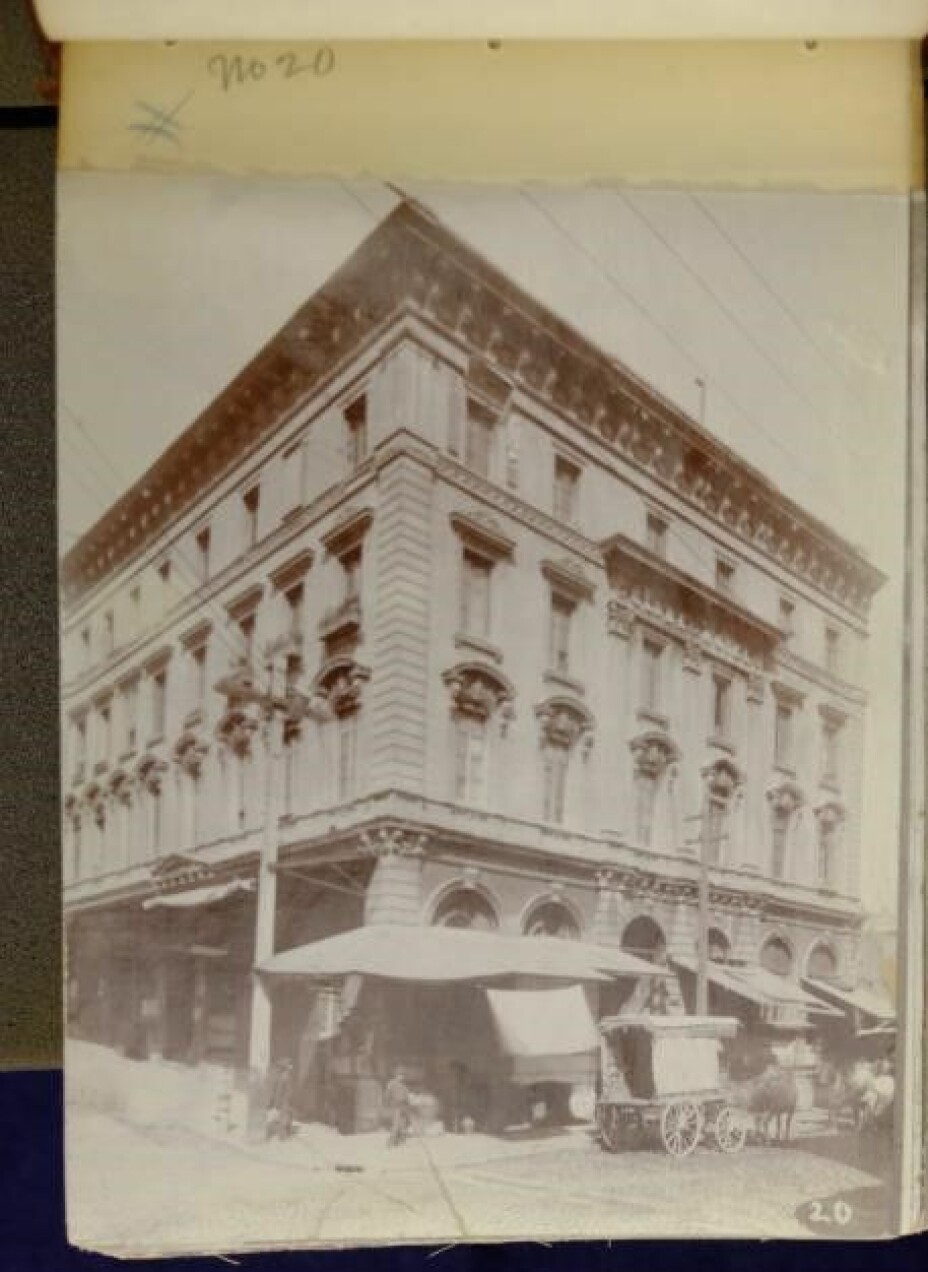

San Francisco - the plague and ‘the yellow peril’

On the west coast of the USA, people lived in constant worry that the plague would arrive from Asia via the Pacific Ocean.

The plague was seen as an Asian disease, and the Chinese were considered to be particularly dangerous carriers of the infection.

At the same time, a general distrust of Chinese people prevailed. There was talk of 'the yellow peril', and, in 1882, the ‘Chinese Exclusion Act’ was passed to prevent an influx of Chinese workers.

This was also the case in San Francisco, which, with 350,000 inhabitants and a Chinatown of 10,000, was one of the most important ports on the West Coast.

'Keep California White'

When a suspicious death in Chinatown was reported in March 1900, authorities immediately intervened and quarantined the entire area.

It was a severe and unprecedented intervention that was linked to strong anti-Chinese sentiments amongst the central decision-makers of the city.

At a later stage, the city's mayor tried to get elected to the Senate with the slogan: ‘Keep California White’. However, the authorities had to back out again after a few days.

It may have been the case that people were more afraid of the Chinese than of the plague – but it was too much to strike down on an entire population due to a single unconfirmed case of the plague.

The plague disappeared on the West Coast. But…

Nonetheless, the plague had arrived in town, and the authorities tried several times during the spring of 1900 to tie a ‘cordon sanitaire’ (a limitation of movement to or from a defined geographical area, ed.) around Chinatown. There were also plans to demolish the area.

In San Francisco, however, health authorities faced resistance from several quarters – first and foremost from the Chinese community but also from the local press, commercial interests and particularly from the courts.

The latter twice forced the authorities to lift quarantines and other measures aimed specifically at the Chinese population on the grounds that they were discriminatory. Furthermore, in the year 1900, the USA was a society that placed individual rights over and above collective health measures.

Gradually, the plague outbreak subsided, and in 1904 the number of deaths stood at 121. It appeared that San Francisco’s Chinese inhabitants had overcome both the plague and the racist prejudices.

But in the bigger scheme of things, they did not win. Just as the plague outbreak had come to an end, the ban on Chinese immigration to the USA was made permanent.

Earthquake caused new outbreak

San Francisco's battle with the plague was not over, however, for in 1906, the city was hit by one of the most violent earthquakes in recorded history.

Rats swarmed out of sewers and destroyed buildings – and they brought with them a new outbreak of the plague.

Another campaign against the spread of infection was launched, and this time with considerably greater success.

Between the two plague outbreaks, a greater understanding of the transmission processes of the plague had been achieved, and it was now understood that efforts should be directed towards rats and not minorities.

What we can learn today from the third plague pandemic

Epidemics are not all alike, and there are obvious differences between the third plague pandemic and the current outbreak of coronavirus.

If we use the third plague pandemic as an indicator, however, we can see that the same disease can have different effects in different, concrete contexts.

We can also observe that the health crisis back then interacted with and underscored developments that were already underway.

The Indian nationalist movement existed before the plague outbreak but was strengthened by it.

The plague was not the 'cause' of racial segregation in South Africa but acted as a catalyst for its further development.

The plague outbreak in San Francisco provides an early version of a society where authoritarian, state interventions are struggling, and it cemented a widespread anti-Chinese racism.

When Trump today refers to 'COVID-19' as the 'Chinese' virus, it thus follows a tradition of blaming disease outbreaks on others.

These examples indicate that contemporary social scientists should keep a close eye on the trends that were already on the rise before the outbreak of COVID-19.

Among the obvious candidates are increasing digital surveillance, a stronger China and more nationalism. But we do not know.

Perhaps the corona crisis will rather become a turning point that provokes surprising and unforeseen developments?

This article is translated by Stine Zink Kaasgaard. Read this article in Danish at Videnskab.dk's Forskerzonen.

Sources

———