Citizen science: How you can help scientists

Scientists need you! Sign up for a citizen science project and help to make all of us that little bit smarter.

Even amateurs can produce a worthwhile piece of science and increase our knowledge about the world around us. You do not even need to leave the couch.

Everyone can take part in scientific projects and there are lots to choose from. Citizen science, that is, science conducted by people with no formal scientific training, covers many different areas. You can help out with anything from counting mushrooms to investigating the development of the universe.

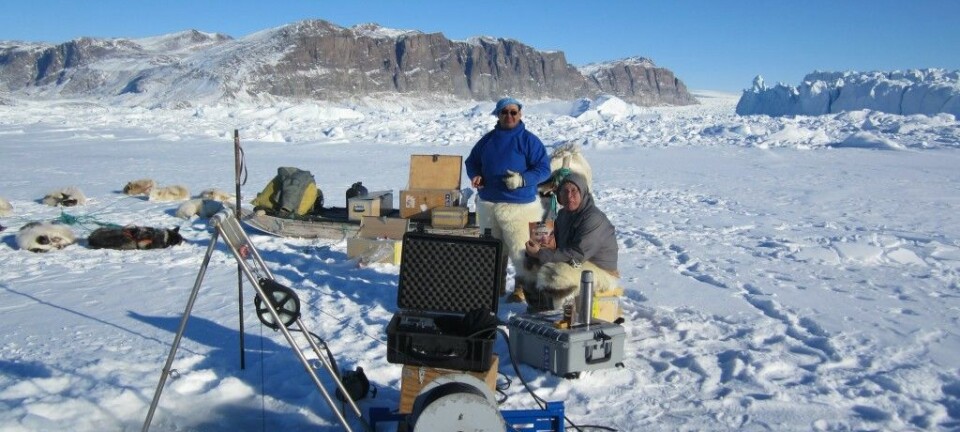

Some projects require you to head out into nature but most can be completed from home at your computer or on your smart phone.

35,000 nature spotters

Scientists from all other the world need your help. One example is Big Nature Check, one of Denmark’s largest Citizen Science projects, run by The Danish Society for Nature Conservation.

Around 35,000 Danes have taken part in the project by heading out and mapping biodiversity in Denmark, reporting their encounters with animals and their habitats.

“We’ve received 390,000 observations since we launched our app, Nature Check [only available in Denmark] in May 2015. Our goal is to collect 150,000 observations every year until 2020 across all the regions in the country. This is the basic data that scientists need,” says project leader Simon Leed Krøs.

A few things need to be taken into consideration when launching such a project. For example the scientists need an even data coverage across the whole country to see trends in biodiversity.

But most people live in cities. So the project team behind Nature Check made additional efforts to recruit citizen scientists in sparsely populated areas through partnerships with Scouts, farmers, hunters, and school children.

Read More: Citizen Science in the Faroe Islands: Helps both hunters and animals

Needs to be done properly

The organisers have also worked hard to ensure that the app is both user friendly and that the data quality is high.

The app’s users are not biologists and can struggle to identify the different species. So only a limited number of species are included in the check list.

“We’ve chosen 30 species that are easy to recognise. They need to be difficult to confuse with others and a school child should be able to recognise one species in a few seconds. That’s been achieved,” says Krøs.

The scientists screened all of the data collected during the first year and they look sensible, he says.

“Our failure rate is not very big and we can clean up the mistakes. And we always encourage users to clean up and delete incorrect entries. And they’re good at it,” says Krøs.

“In our new version of the app, we’ve also included an “are you sure” button for some of the plants and mushroom species that people can have difficulty recognising. We hope that gives an extra guard against mistakes,” he says.

Read More: Help scientists map the bacterial jungle in your shower

Few species tell a bigger story

Of course, it is not enough that the species are simple to identify. They should also be of scientific interest and indicate what is happening out in the wild. So the scientists behind the project identified particular species that could act as indicators of the state of nature.

The species are not rare or endangered, but they tell a story of how many different types of habitats are faring, which many more species depend on.

By the time the project ends in 2020, scientists will have a wealth of data to analyse to see how Denmark’s biodiversity is faring.

Read More: Archaeology is being revolutionised by amateur collectors

What do the pictures show?

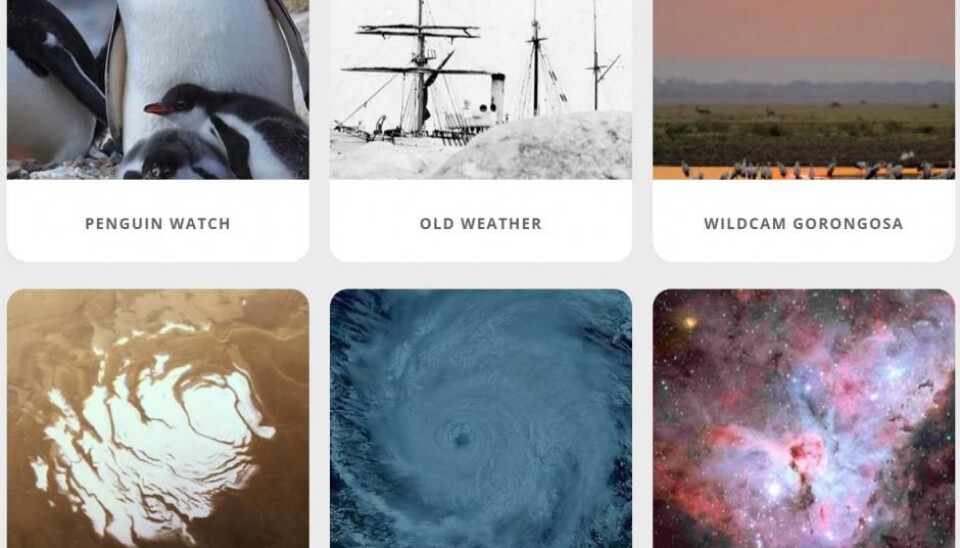

A list of citizen science projects from all over the world can be found in the Zooniverse web portal. Many projects simply require you to look at photos and identify what you see.

Many projects exploit the ability of the human brain to recognise patterns. For example, we are very good at recognising an elephant, even though we can only see an ear and a bit of the trunk.

Such tasks are hard for computers, so researchers need volunteers when analysing mountains of photos.

------------------------

Read more in the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex