Professor: rising inequality could lead to a revolution

Danish economists fear inequality will keep growing and they worry about the consequences. In the worst event, there could be a revolution.

If inequality keeps growing, it could lead to an outright revolution. That’s the message from Jesper Jespersen, Professor of Macroeconomics at Roskilde University, who says rising inequality will lead to social and political unrest.

“The current developments can’t go on forever, because that would mean that all income would go to the affluent in the end. And then there simply isn’t anything left for wages for ordinary people,” says Jespersen.

“If the wage share is continually lowered, a revolution could break out, as Marx predicted,” he says, but adds that the rising inequality isn’t a law of nature and politicians will probably intervene before the torches and hayforks are raised in the air.

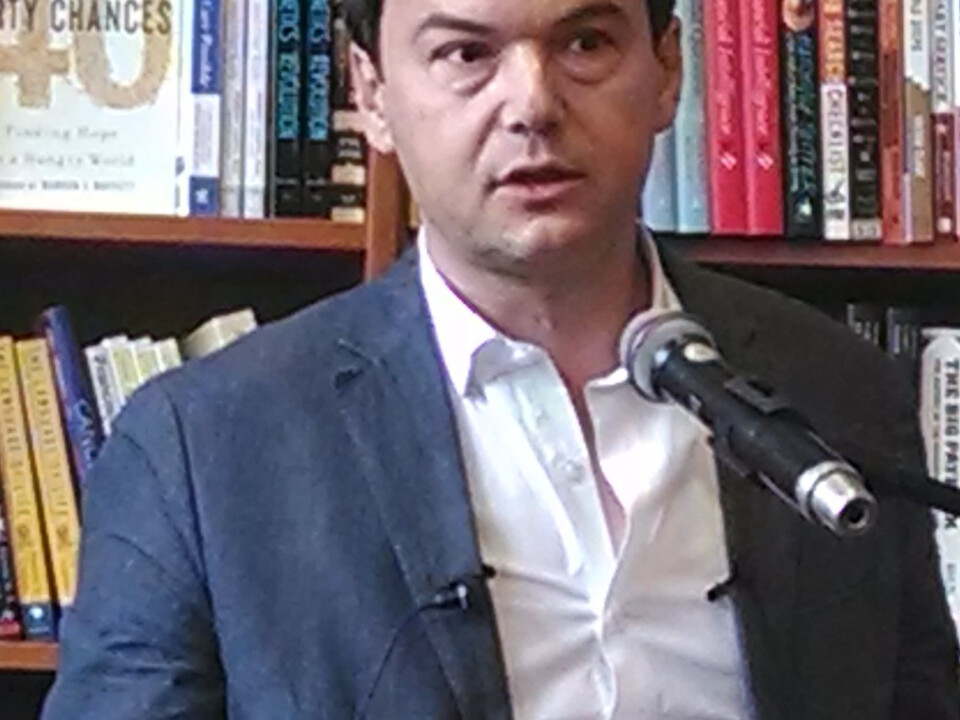

Jespersen’s wagging finger comes in the wake of the monumental work ‘Capital in the 21st Century’ by the French economist Thomas Pikkety.

In his book, Pikkety uses an extensive collection of data to demonstrate that inequality has generally been on the increase since the 18th century and is likely to keep growing in the future.

The public will demand change

Katarina Juselius, Professor of Economics at the University of Copenhagen, has followed Pikkety’s work from the sideline for years. She agrees with his prediction that assets will be divided between fewer people, and that this will lead to a rise in inequality.

However, Juselius isn’ worried about a revolution in the near future:

“I don’t believe that capitalism will be replaced by another system. It’s utopian. But I do think that public pressure on politicians to make changes will be so great that they’ll have to counteract the rising inequality with progressive taxation and more redistribution.”

Could democracy turn things around?

Economist Christian Gormsen doesn’t worry about a revolution either. However, nor is he certain that political changes will tackle the growing inequality.

He worries that the current developments will simply continue, and that this will mean a hitherto unforeseen degree of inequality.

“I won’t rule out that inequality will simply continue to grow as far as the eye can see. In the US, inequality has grown explosively since the 1970s -- the richest 10 per cent of the American population appropriates the same proportion of the American economy today as they did in 1910. And Americans have only recently started to seriously discuss inequality,” says Gormsen, who is economist and analyst in the Danish centre-left think tank Cevea.

Gormsen notes that on the whole it’s uncertain how much inequality it’s possible to have in a society, before the pressure for change grows too large to maintain the status quo.

“It’s a fascinating question. We know that the market itself doesn’t ensure equality. To the contrary, there’s a tendency towards growing inequality in a market economy. But are the politicians able to stabilise that tendency, and will they do so? Our historical experience perhaps points in the direction of a ‘no’ to that question,” says Gormsen.

Future consumption of capital owners will be decisive

Carl Johan Dalgaard, Professor of Economics at the University of Copenhagen, recognises Pikkety’s rationale. However, he points out that inequality doesn’t automatically grow, just because fortunes grow faster than national economies. He explains that the fortunes’ share of the overall economy depends on how much those in possession of the assets spend and invest.

“If the return of the capital is solely spent on consumption, the capital won’t grow. Whether inequality will hit the level it was at prior to the First World War, or if it will stabilise at the high level we are currently witnessing, depends on how much of the return the capital owners spend and how much they will invest,” says Dalgaard.

Gormsen agrees that the consumption and reinvestments of capital owners is central to how inequality will develop in the future. However, he believes that it’s unlikely that the richest capital owners will mobilise a larger proportion of their assets for consumption than they have previously done.

“Today, there are magazines for rich people who need inspiration for how to spend their fortunes. I can’t see why the richest capital owners should suddenly start invest a significantly smaller proportion of their returns,” he says.

Translated by: Iben Gøtzsche Thiele