“Yeti” samples are actually from bears

DNA analyses of nine “Yeti” samples of bone, hair, and faeces, originate from bears. But is it conclusive proof that the Yeti does not exist?

According to legend, the abominable snowman, also known as the Yeti, is a dangerous man-eating creature that comes down from the Himalayas to snatch cattle and young girls.

The story has been told for generations, but despite the wild stories, spectacular foot prints, and even Yeti trophies, scientists have not identified the creature behind the myth.

This all changed in 2014, when geneticist Bryan Sykes from Oxford University, UK, analysed the DNA from tufts of hair from a supposed Yeti and – under intense media attention – proposed that it was simply an unidentified species of bear.

Scientists: The samples came from a dog and a bear

Scientist have analysed the DNA from nine samples of hair, teeth, bones, skin, and even faeces, all of which are said to belong to a Yeti.

The DNA revealed that one sample came from a dog, but all others from local bears.

“Our results strongly suggest that the biological basis for the Yeti myth is local bears and the study shows how genetics can be used to clarify other similar mysteries,” says study leader, Charlotte Lindqvist, an evolutionary biologist at the University at Buffalo, USA, and guest professor at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

Read More: Fossil DNA identifies the first seafarers in the Pacific Ocean

Does not disprove existence of the Yeti

The results were welcomed by Denmark’s only cryptozoologist, Lars Thomas, who is associated with the Centre for Fortean Zoology in the UK.

“It’s good that someone has now looked into Sykes and co’s grandiose statements from the first DNA analyses,” says Thomas.

“But even though it naturally weakens the entire Yeti myth, it actually does not prove that the Yeti doesn’t exist. It only shows that the samples that we have until now associated with a Yeti come from bears,” he says.

The study is published in the scientific journal, Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Read More: Animals that might exist

Is the Yeti a polar bear from Svalbard?

Lindqvist is neither a cryptozoologist nor a Yeti expert, but one of the world’s leading experts in bear evolution.

She was drawn to the riddle of the Yeti ever since Sykes and colleagues discovered mysterious DNA in two purported Yeti hair samples, from India and Bhutan.

Both tufts of hair contained bear DNA, but not from any known living species of bear. The closest match was the fossil DNA from a 120,000 year old piece of jaw bone from a polar bear discovered in Svalbard.

“It was a polar bear that I had worked with,” says Lindqvist.

A film crew from Icon Film Company had followed Sykes’ Yeti hunt closely while filming the Big Foot Files, and they turned to Lindqvist to see what she made of the discoveries.

“I thought it was a bit strange if it had been a polar bear in the Himalayas,” she says.

“DNA analyses were very limited so I questioned the conclusions and told the film crew that if they wanted to follow up on this, then they needed to have more thorough DNA analyses and more samples,” says Lindqvist.

Read More: The ‘Godfather’ of bioarchaeology is moving to Denmark

Sampled Yeti mummies, relics, and thigh bones

The film crew took her advice and traveled to Nepal to collect more samples.

Some samples came from museums and private collections, such as teeth from a stuffed “Yeti” owned by the famous mountaineer, Reinhold Messner, who spent years searching for Yetis after he claimed to have seen one near a Tibetan monastery in 1986. (Today Messner is convinced that the Yeti was in fact a bear.)

Other samples included Yeti faeces owned by Messner, skin from a relic Yeti hand, which the film crew found by a Tibetan monastery, bone dust from a human-like thigh bone discovered in a cave in the Himalayas, and tufts of hair similar to those analysed in Sykes study.

Lindqvist received the samples in small bags with no knowledge of where they came from and analysed them using a method developed to investigate fossil DNA.

Read More: How to track down your ancestry with DNA

Film crew were disappointed

Like Sykes, Lindqvist and colleagues studied the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is inherited by the female line and indicates relatives and distinct species.

But where Sykes investigated a single area of mtDNA, Lindqvist went further and mapped the more variable parts of the DNA and in some cases, even the entire mitochondrial genome to identify the species.

The results showed that none of the samples came from a Yeti-human ape or an unknown aggressive prehistoric bear.

“I must admit that that the film crew was rather disappointed,” says Lindqvist.

“But they took it well and said, ‘science is science and these are the results that we arrived at,’ and that’s that,” she says.

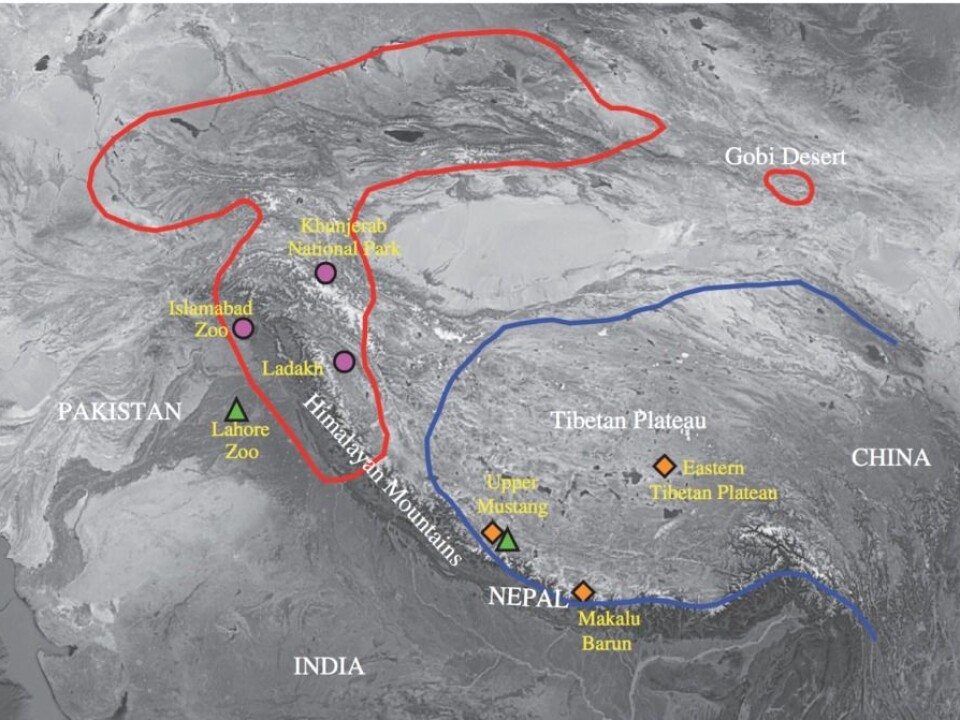

Apart from the one sample (the tooth from Messner’s “Yeti”), which turned out to be from a dog, the samples matched three different local bears: the Asiatic black bear, Himalayan brown bear, and the Tibetan brown bear.

Read More: DNA confirms Australian Aboriginals are the oldest civilisation still around on Earth

Is the mystery solved?

“For me the mystery of the Yeti is now solved, but there will probably be people who say ‘well yes, these samples are from a bear.’ But I think that I’m convinced,” says Lindqvist. Although she is sure that the myth will persist.

Thomas points out that strictly speaking, it does not disprove the existence of the Yeti.

“Just one positive hair sample will prove the existence of the Yeti, but even this many negative samples do not prove that it doesn’t exist,” he says.

But he adds that “the many negative samples clearly reduces the likelihood,” and suggests that the local eye witnesses may not be quite as reliable as once thought.

---------------------

Read more in the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex