How pollen in water can foretell the spread of malaria

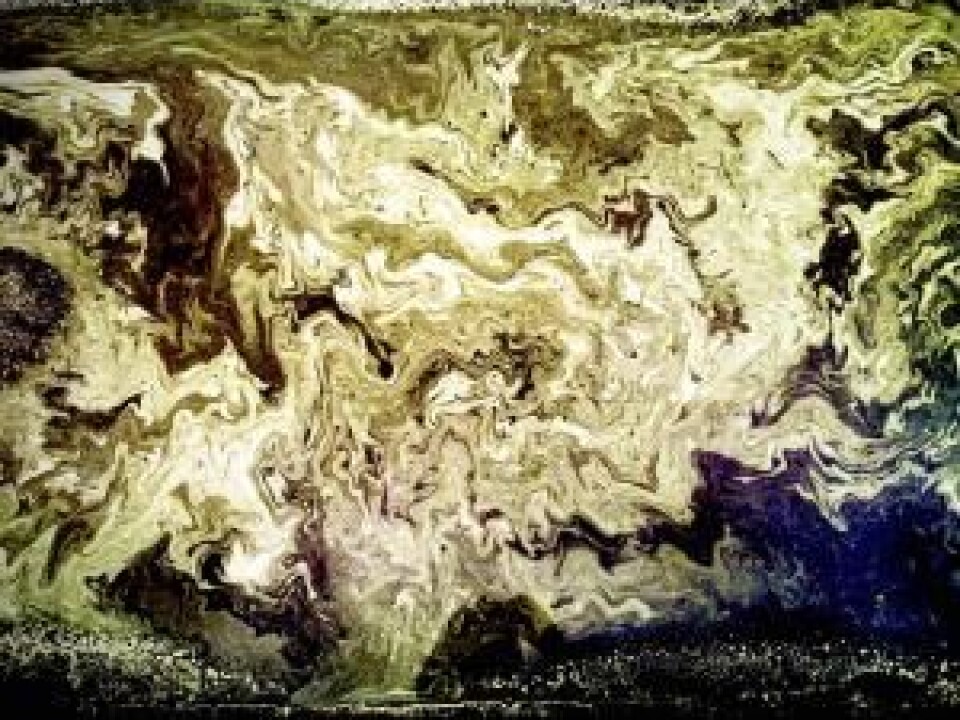

Danish physicist wins first prize at international photography competition with his image of a puddle that depicts how wind and rain help spread malaria.

One rainy and windy day in 2012 provided Danish physicist Kaare H. Jensen with an ideal photo opportunity: a puddle in front of Harvard University.

It had been a high pollen year, and the wind had shaken the pollen from the trees and mixed it with rainwater on the ground.

Jensen immediately saw what was going on and snapped a photo.

That photo has now been awarded first prize at the American Physical Society's major annual meeting in Boston, USA.

But despite its beauty, the image also portrays a sad story about how malaria can thrive in standing water.

"Stagnant water is the root of all evil," says Jensen, who works as an assistant professor in the Department of Physics at the Technical University of Denmark.

You can find the original image and other entries at the American Physical Society's website.

The wind helps malaria

The picture shows how small nutrient particles move in puddles.

"Puddles are interesting because the malaria mosquito larvae feed on bacteria in the surface layer in puddles in many countries in the tropics," says Jensen.

When the wind blows it makes the puddle surface ripple, something the mosquito larvae love.

"It means that the nutrients are mixed around so they [mosquito larvae] have more food," says Jensen.

Learning more about how nutrients reach malaria larvae could help fight the spread of malaria, he says.

Pollen grains act as a liquid

The swirls are made up of tiny pollen grains. Measuring just 0.01 to 0.05 mm in diameter, the grains are indistinguishable to the naked eye.

The pollen falls from the trees as a blob and becomes dispersed in the water.

"The liquid becomes mixed and you can see that the patches of pollen are stretched and folded into each other," says Jensen.

------------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex