Dementia patients embrace GPS surveillance

Elderly Swedes with dementia want to be tracked by GPS, even in their own homes.

Patients with dementia can live at home with the proper support. Both they and their families can enjoy more freedom and security in their daily lives, according to research from Sweden’s University of Gävle (HiG).

“Our study also showed that all dementia patients in the study wanted the surveillance system in their homes,” says Annakarin Olsson, a professor of medicine and nurse at the Faculty of Health and Occupational Studies at HiG.

Increased freedom

The project, led by Olsson, involved cooperation between the researchers, the Municipality of Gävle and a technology firm.

Five couples, in which one of the spouses was a dementia patient, participated in the study.

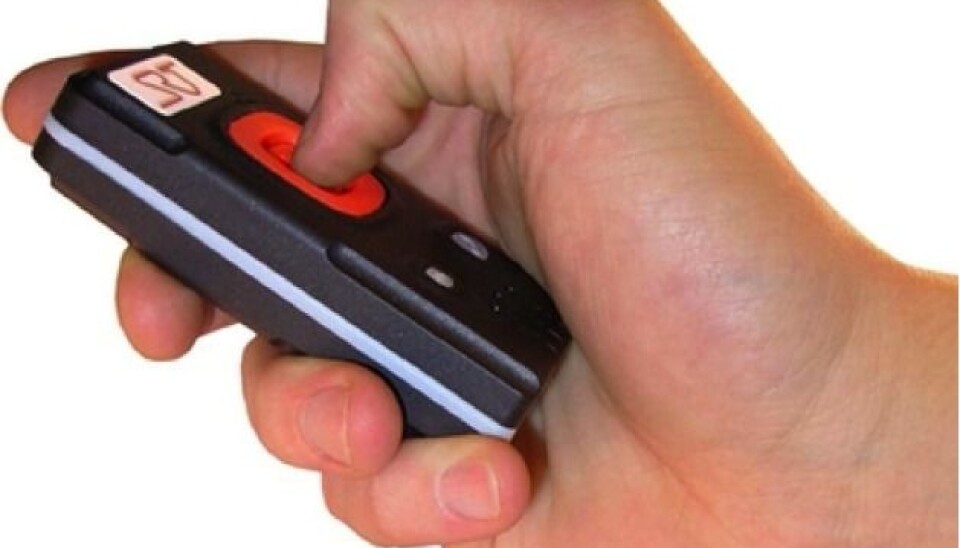

“A transmitter was carried by the dementia patient and the receiver, a common mobile phone, was kept by the spouse. Telephonic contact can be made between the transmitter and the receiver,” explains Olsson.

She says the system was developed to act as a support for dementia patients who want to be outdoors. It was not meant to function as a complete surveillance tool, so the patient’s movements within the house were blacked out in the project.

“Outside the hidden zone, which is the home, the transmitter provides an exact GPS position for the person. People with dementia thus have more security, independence and freedom to walk about outdoors.”

“Research shows that the opportunity to engage in outdoor activities is very important for people with dementia. It becomes much more important for them to be able to have undemanding experiences and activities, largely because social interaction is complicated by communication problems. In addition, the alarm function gives spouses and family more peace of mind,” explains Olsson.

Interviews both during and after the project showed that everyone involved would like to have the person with dementia's movements both inside and close to the house visible to the spouse as well.

The system that was tested for the study blacked out a radius of 500 metres around the house as a blind spot, and spouses couldn’t follow their dementia-stricken partner’s movements inside this area. But many of the dementia patients felt insecure with such a long electronic tether, because some were afraid of getting lost even in their own gardens.

Illegal in Norway

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health says some 70,000 people in the country have been given a diagnosis of dementia. These patients take up about a third of all the hospital or nursing home beds in Norway. The National Association for Public Health estimates that roughly one-quarter million family members are affected by having relatives with dementia.

“Unlike in Sweden and Denmark, it’s illegal in Norway to equip dementia patients in public health facilities with tracking technology. Given that by 2050 there will probably be twice as many dementia patients, and that nursing homes and care facilities will be hard put to take care of them all, we really should be collaborating and looking into approaches like this,” says Olsson.

However, it's not the Norwegian Data Protection Authority or general rights of privacy concerns that are keeping these kinds of GPS alarm systems from being used in Norway’s public health services.

The hitch is in the public health care regulations themselves, which stipulate that a dementia patient must be lucid enough so that he or she understands the meaning of the tracking technology and what it comprises.

“Are we protecting the integrity of dementia patients and preventing infringements on their private lives, or are we ending up with something that people with dementia don’t really want? The findings in the study suggest the latter,” says the researcher.

Want to stay at home

How do you know that the dementia patients in the study knew what they were agreeing to allow?

“They all had either a mild or moderate stage of dementia. Besides having to operate the positioning alarm when they went around outdoors, they were also interviewed about their experience of using this technology,” Olsson said.

“The families were also interviewed and that gave us a good picture. We can’t generalise and say all our findings are valid, but they provide a good platform for a larger continuation study around our findings,” she added.

The study from Gävle shows that dementia patients want to keep living in their homes as long as possible. Their spouses and families want this, too.

“This was a clear and unambiguous wish from both groups. The issue is not just that there will be larger populations of the elderly in the future and that this will strain health care budgets. This is about meeting the wishes expressed by persons with dementia and their families,” Olsson stressed.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling