Green transition: The whole world can learn from a small town in Iceland

A small town in northern Iceland has gone almost CO2-neutral. Researchers went there to find out how they did it and what we can learn from them.

Nowadays cities are quite unsustainable places. They consume a lot of the world’s resources and account for more than half of the world’s emissions of greenhouse gases, contributing substantially to the ongoing climate crisis.

But cities are also the places where a lot of our sustainability problems can be addressed effectively. A small town in northern Iceland has gone a long way to show us how.

I have been to Akureyri a couple of times myself, but to gather some more information my colleague Rakel Kristjansdottir went up there and brought home some truly inspiring field notes for us to study.

Iceland has spectacular conditions for sustainability

Iceland is well-known for its stunning nature, fermented food of questionable taste and eccentric contributions to the European Song Contest. And Iceland is also a very interesting case for us researchers who study energy systems.

The island is blessed with excellent conditions for hydropower and geothermal energy. This abundance of energy helped improve the living condition of the people but in recent years it has also led to big problems.

And while emissions from heating and electricity are pretty low for Icelandic households, per head emissions from transport and other kinds of consumption are still very high.

Two champions from the Icelandic town of Akureyri, Guðmundur Sigurðarson and Sigurður Friðleifsson, were not willing to accept this unsustainable status quo.

About a decade ago, they initiated an ambitious low-carbon transition that now affects all local citizens and turned Akureyri into a frontrunner of climate policies nationwide.

We wanted to know how they managed all this, so we went to do fieldwork at a place that some would call the end of the world.

Waste that does not go to waste

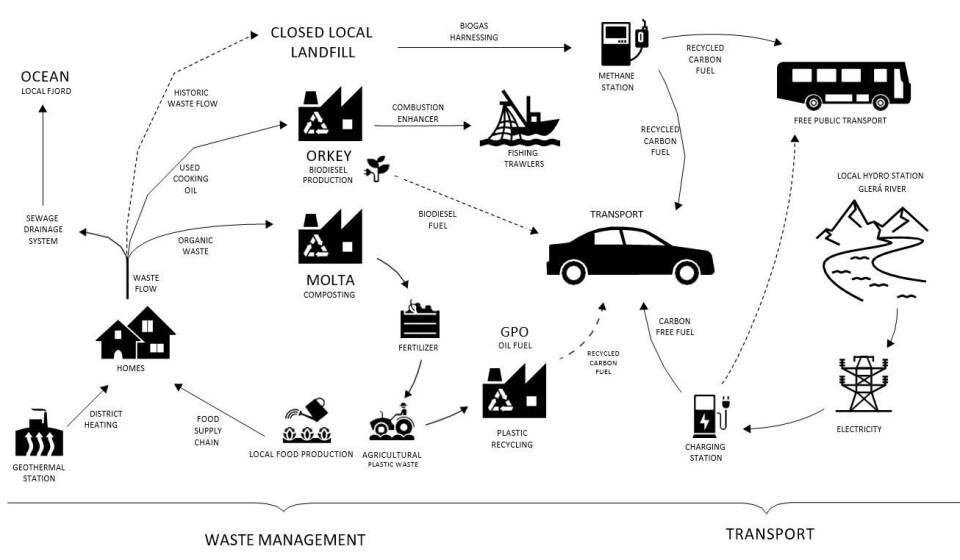

The key factor to the transition was that Guðmundur and Sigurður took all carbon flows of the town into consideration.

This means that they looked at all the materials that flow through a city, such as cooking oils, gasoline, green waste from public parks and assessed how these flows could be integrated into the local energy system.

Then they developed an ambitious strategy that aimed at turning the linear carbon flows of the community into loops.

So, instead of having something flow into the city, using it and having it flown out as waste, they tried to use all materials for new purposes (see figure below).

Busses driving on old cooking oil

The local transport sector plays a central role. The new system turns old cooking oils and gas from the old landfill into fuel for local cars and busses, which, by the way, are free to all inhabitants and visitors.

At the same time, a local afforestation project helps to build up local carbon stocks.

Apart from the carbon flows, the new approach in Akureyri makes sure that nutrients are not lost but remain in the local food production system. Organic waste is now composted and nutrients are used for local agricultural production.

This helps save emissions because local farmers need less artificial fertilizers.

What makes Akureyri ideal for a green transition?

Our research in Akureyri unveiled a number of local characteristics that played out to the advantage of the transition.

First, Akureyri has an ideal size. The town has 18.000 inhabitants and is the biggest urban centre in the North of the country.

With this size, the city has all the required institutions and companies in place, such as a local public transport system and a local energy company. At the same time, it is so small that key actors know each other personally and complicated administrative procedures do not hamper new projects.

Second, Akureyri is the centre of education in the north. The town hosts a well-known university and one can generally find an atmosphere open to new ideas and innovative concepts.

Third, the local actors created the right institutional frame for the transition. A key factor for this was the establishment of a local company called Vistorka, run by Guðmundur.

This company became the ‘spider in the web’ that brought all the different companies and institutions together to implement the ambitious low-carbon plans.

Fourth, the two champions mentioned above played a very important role. Others from the community describe them as a team that combines the political skills (Guðmundur) and the technical expertise (Sigurður) needed to understand what is possible and how to achieve it.

Benefits from transition – the obvious and the not so obvious

The local low-carbon transition in Akureyri has brought about a number of benefits.

The most obvious one are the environmental improvements: lower greenhouse gas emissions, less plastic waste and lower loss of nutrients. The afforestation project has created a nice green area that the inhabitants can use for recreational activities.

Then there are the less obvious advantages. The project has created a number of new local companies and jobs in the environmental sector. They have helped to increase local economic activity in Akureyri, creating additional tax income for the municipality.

Finally, Akureyri has created a strong image as environmental leader in Iceland.

The world can learn from Akureyri

Now, what can the case of Akureyri teach urban planners and politicians in other towns?

To begin with, low-carbon transitions are possible, even in remote places like Akureyri. If done properly they can unfold benefits for the global and the local level.

Urban mangers have to look at the entire city and consider all material flows. Only then, can they discover possibilities to link those flows to make urban systems more sustainable and low-carbon.

And finally, intermediaries like local champions and organisations play a key role in bringing different actors and their interest together and by that managing change in a community.

We hope that these lessons can help citizens, politicians and urban planners in other cities to tap into the full low-carbon potential of their city, town or community.