Greenland has lost 9,000 billion tons of ice in a century

For the first time, scientists have calculated how much ice has disappeared from Greenland in the last 115 years.

Scientists need to know how much of the Greenland ice sheet will melt in order to predict future sea level rise. They also need to know how much of the ice has already disappeared.

While they can answer the first question by monitoring the extent of ice from year to year, the second question has proved somewhat elusive due to a lack of data before satellites routinely monitored the extent of Greenland ice.

But now a group of scientists have calculated how much of the ice sheet has been lost in the last 115 years, using old aerial photographs.

The new results provide important data for the next report from the UN International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which up until now has been unable to fully estimate the total amount and speed at which ice has melted in Greenland before routine monitoring by satellites.

"It’s a real advance for our understanding of ice sheet history, and we can see that they are melting much faster now than at any other time in the last 115 years,” says Associate Professor Shfaqat Abbas Khan of the Institute for Space Research and Technology on Technical University of Denmark (DTU).

The study has just been published in the scientific journal Nature.

Rapid Ice Melt

The new research is particularly relevant in understanding all the factors that cause global sea level to increase, says Peter Langen, a climate scientist from the Danish Meteorological Institute who was not involved in the new research.

He describes it as an impressive and important piece of work.

"The new study puts today’s ice melt into [a historical] context. This helps us to improve our predictions of future sea level rise," he says.

According to Langen the new study will show if the current loss of mass from the ice sheet is a new phenomena, or whether similar losses have happened before.

"The new data clearly indicates that what we are seeing now is remarkable. It means that we can put the current mass loss from the ice sheet in a longer time perspective," says Langen.

Oceans rose 25 millimetres in the 20th century

The new study is the first of its kind to reconstruct the amount of ice lost from the Greenland ice sheet in the 20th century, based on observations rather than model predictions.

In the 20th century, Greenland has lost around 9,000 gigatons of ice, accounting for 25 millimetres of sea level rise that is missing in the latest IPCC report.

According to Professor Jason Box from Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, the new data will make the predictions of climate change and sea level rise even more robust.

"It’s an elegant study in which we use the information from the landscape and old photos to reconstruct the loss of ice since 1900. It provides a more complete picture of how Greenland has changed over the past 11 decades," says Box.

The first large-scale survey of the ice sheet history

Scientists study the changing Greenland ice with computer models. But these models are based on observations from satellites, which are only available since 1992.

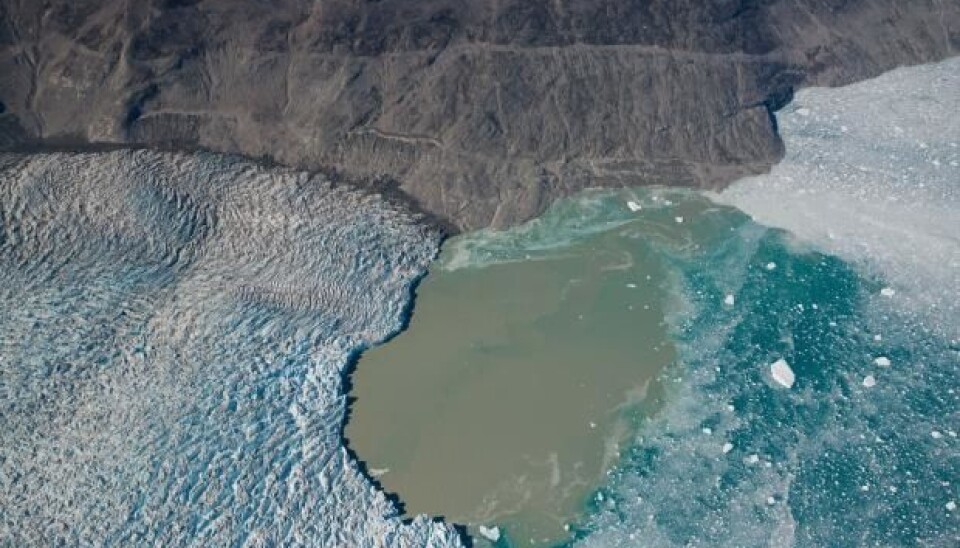

So they needed a new source of data to reconstruct the ice sheet history further back in time, which they found in old photographs depicting landscape features known as trim-lines.

Trim-lines depict how high the ice sheet has been in the past.

By studying these features, they could determine how much ice has disappeared.

More storms on the way

The new data will improve predictions of future sea level rise, says Khan.

“When we look over a longer period, we get a more accurate picture of what the trend is and we can use this to improve our estimates of sea-level rise," he says.

But according to Box, Greenland ice melt has more immediate consequences.

"The increasing loss of freshwater from the ice sheet accumulates in the sea around Greenland, where it cools the ocean. We’ve observed falling temperatures in the North Atlantic in recent years, while the world has been experiencing record breaking warmth,” says Box.

“This might create stronger storms in Northern Europe, which will be felt well before the water level increases," says Box.

---------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex