Trees survived the Ice Age in Scandinavia

The genetic structure of ancient trees suggests that we may have to rethink how life reacts to climate change.

Contrary to the established view, new research shows that conifers grew in northern Scandinavia in the glacial period despite several kilometre thick ice sheets.

Up to now, most scientists have subscribed to the general view that the advancing ice presented all living things with an ultimatum: Go south or die out!

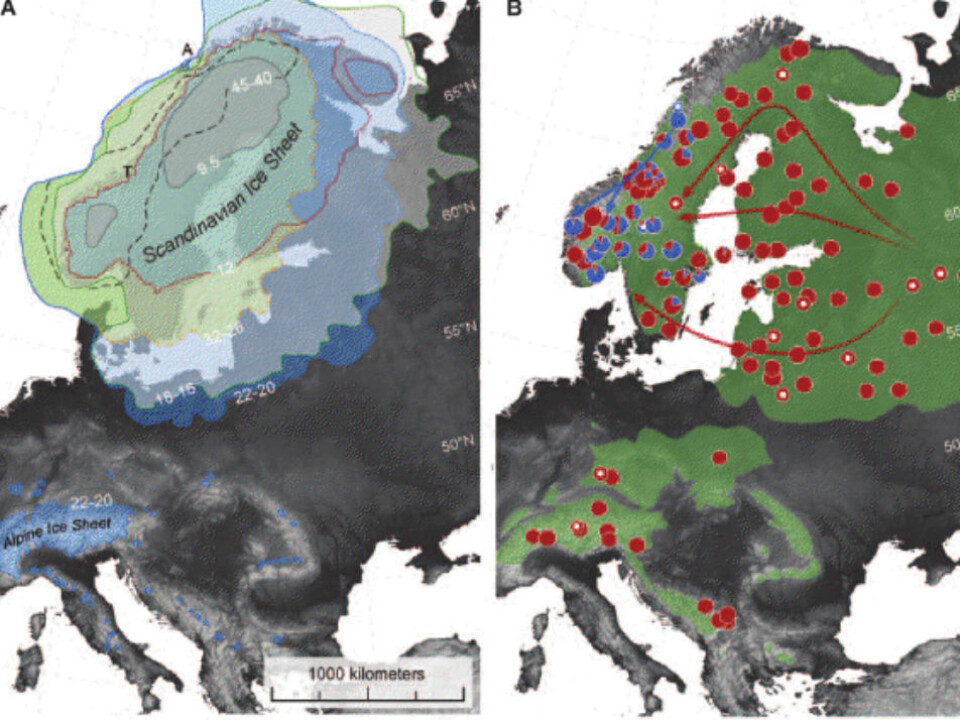

But now an international research team claims that the glaciations has not been total, and that there must have been some retreats with ice-free areas where trees could survive tens of thousands of years of glaciation.

“This means that we need to rethink how life reacts to global climate changes and that life on Earth is a lot more robust than we think,” says Professor Eske Willerslev, of the Centre for Geogenetics at the University of Copenhagen, who headed the research.

Generally accepted that the trees disappeared

Willerslev and his colleagues used the latest DNA technology to gain a fresh view on a controversial issue about the origin of the Scandinavian forests.

It has long been generally accepted that all trees in Scandinavia disappeared completely during the last Ice Age, which started some 115,000 years ago.

This view states that it wasn’t until after the ice melted away some 9,000 years ago that the trees started to reappear at an impressive speed from the south and the east.

Trees dated back to the Ice Age

Not all researchers, however, have managed to reconcile themselves to this view. For instance, the Swedish professor of physical geography at Umeå University, Leif Kullman, has found remains of trees throughout Scandinavia, which he dates back to a time before the ice had melted away.

This suggests that there were ice-free areas. But analyses of pollen strata from the Ice Age have failed to find evidence in support of Kullman’s theory.

In a heated debate, many scientists have argued that Swedish professor’s datings were flawed.

But now Willerslev and his colleagues appear to have settled the case in Kullman’s favour.

Two types of spruce

Having analysed the genetic make-up of more than 100 European spruces, the researchers discovered that there isn’t just one type, but two.

One of these occurs exclusively in Scandinavia, where the distribution fits in perfectly with what would be expected if the trees were of the same lineage as the spruce that had survived in the ice-free areas.

It appears that there is a type of spruce indigenous to Scandinavia, which, after the ice melted away, has spread from within Scandinavia.

Meanwhile, the other type of spruce started migrating back to the area from the south and the east.

Combining old and new genetics

The findings look promising; however, the genetic material in present-day organisms cannot provide definite answers about where the trees came from.

This is where Willerslev’s core competence comes into play: as one of the world’s leading fossil DNA researchers he has repeatedly shown in recent years that it’s possible to gain information about the past from tiny DNA fragments retained in soil dating back tens of thousands of years.

Examining soil from the Ice Age enabled the researchers to test the hypothesis.

“This is the first time that modern genetics is being combined with ancient genetics,” says Willerslev.

Mad professor was probably right

Sediments at the bottom of a lake in Trøndelag in central Norway revealed samples of 10,300 year-old DNA, which indicate that the indigenous Scandinavian spruce type was located in central Norway, while the country was supposed to have been covered by a thick layer of ice.

From samples dating back some 20,000 years, they also managed to identify DNA from both pine and spruce on the island of Andøya in northwestern Norway.

“This means that Kullman, who everyone though was mad, was probably right,” says Willerslev.

Animals may have survived too

The discovery is of great importance to the scientific picture of what happened after the Ice Age.

Just as in Scandinavia, there may well have been similar ice-free retreats in Siberia and in North America, and the current models of how plants spread now need to be reassessed.

The researcher points out that small animals such as lemmings may well have been able to survive in these retreats too.

And if these ice-free areas have been sufficiently large, it’s possible that bigger animals such as the stag could also have survived there, says the researcher.

Current models should be revised

In other words, the study reveals that we have a far too simple image of how life on Earth reacts to major climate changes. It also suggests that the models describing what we can expect from the current climate changes should be revised.

Willerslev also points out that it’s likely that the discovery of an indigenous Scandinavian spruce type will have economic implications.

Even though there is no obvious difference between the two types of spruce, they could well have different characteristics.

“We need to ask ourselves whether two tree types that have undergone highly different types of selection couldn't have ended up with different characteristics,” he says.

“What might be referred to as the indigenous Scandinavian spruce has survived some pretty extreme conditions – and that could well have affected, for instance, the quality of the wood.”

------------------------------

Read this article in Danish at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther