This article was produced and financed by The Research Council of Norway

Warmer climate – fewer storms

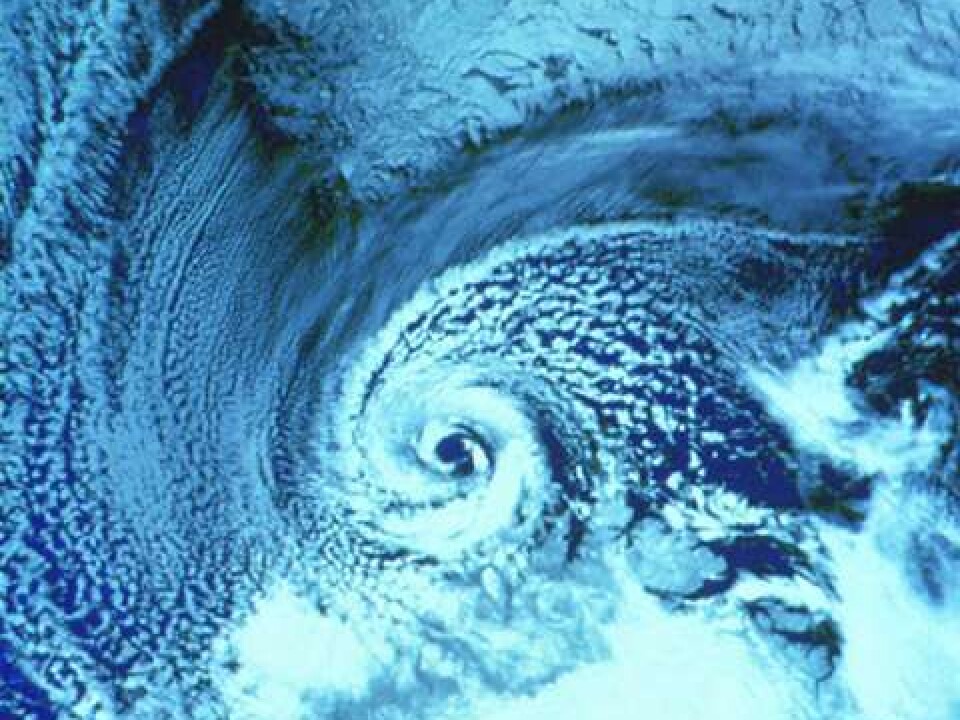

Diminishing sea ice in the Arctic Ocean could mean fewer storms. Researchers have gained new insight into the relationship between climate change and storms caused by polar low-pressure systems.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Severe storms along the Norwegian coastline and in the Norwegian Sea are often caused by polar low-pressure systems.

Roughly half of all such storms have their origin in these systems, which are formed above the sea ice covering the Arctic.

Each winter, an average of 12 polar low-pressure systems develop above the marine areas off northern Norway. These systems can move as far south as the UK.

Difficult to forecast

Meteorologists can predict other powerful low-pressure systems that are preceded by strong winds days in advance. But there are few early indications of the formation of polar low-pressure systems, which often develop so suddenly that ships’ crews are caught unaware, causing many shipwrecks.

These systems often bring major snowfall as well, both at sea and along the coastline.

In recent years, however, Arctic sea ice cover has declined, and a warming climate may exacerbate this even more. This could lead to fewer polar low-pressure systems – and fewer gale-force winds, storms and hurricanes in the northern areas.

Storms farther north

In the research project The Effect of Climate Change on Arctic High-Impact Weather Events (ArcChange), scientists have studied relationships between climate change and polar low-pressure systems.

“We believe the frequency of polar low-pressure systems heading toward Norway will drop. As the extent of sea ice declines in the Arctic, the low-pressure systems should move farther north, missing the Norwegian mainland more,” explains researcher Øyvind Sætra of the Norwegian Meteorological Institute.

"Svalbard, however, may be hit by polar low-pressure systems in the future."

Arctic cyclones

Polar low-pressure systems form when extremely cold, dry Arctic air is carried from ice-covered polar regions and across warmer ocean surfaces. The temperature gradient between the air and water can reach up to 20°C – a temperature shock that creates atmospheric chaos and forms an Arctic cyclone, similar to but smaller than its tropical cousin.

There are forces constantly at work to equalise the difference in temperature between water and air. Vast amounts of energy escape the ocean in the form of heat within water vapor – enough, in fact, to power a cyclone.

Energy from the ocean

Research conducted in the ArcChange project has resulted in a whole new level of understanding about how the ocean supplies the energy for polar low-pressure systems. Knowledge about the dynamics of heat energy transfer from marine waters to the atmosphere is vital to international climate research.

Researchers have isolated the various physical processes of a polar low-pressure system. This has led to a better understanding of the role of factors such as waves and wind in the development of a cyclone.

Wind is to blame

By dropping a total of 147 sondes (atmospheric sensors) into a cyclone from an altitude of 10,000 metres, the researchers were able to map the entire two-day progression of a polar low-pressure system. The team created a three-dimensional depiction of the pressure system; this data could prove valuable in future research.

“A common hypothesis,” says Sætra, “has held that preceding the formation of a polar low-pressure system, the air down near the marine surface amasses huge amounts of what we geophysicists call CAPE - convectively available potential energy. But we found no such CAPE when we released our sondes to float down through the storm, so we have now concluded that it must be the wind that whips up the entire energy transport from the ocean to the air.”

Warmer ocean temperatures not a factor

Until now, many climatologists have believed that global warming and higher ocean temperatures would cause the transfer of more energy from the water to the atmosphere, stirring up higher winds and more storms.

The ArcChange researchers believe that higher marine temperatures have practically no impact on polar low-pressure systems, because in a warmer climate the atmosphere is heated more quickly than the water. Thus the temperature gradient between the ocean and atmosphere would be more likely to decrease rather than increase.

Translated by: Darren McKellep/Carol B. Eckmann