More heavy rains in the future

Increasingly powerful cloudbursts can wreak havoc in cities. Better measurements and climate models can help urban planners protect cities from wetter, wilder weather.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Jan Erik Haugen says it's not just your imagination. “Heavy showers are more frequent," than they used to be, he says.

Haugen is a researcher at the Norwegian Meteorological Institute in Oslo and a participant in a European project that is working to predict how precipitation will vary due to climate change and natural variations.

These are not your run-of-the-mill weather forecasts. The predictions the researchers are working on are for the next several decades.

Nor do these efforts try to predict the individual squall. Instead, they are focused on the likelihood of extreme precipitation, or how often cloudbursts will come, and how powerful they will be.

“Short bursts do much more damage in cities than steady precipitation over long periods," Haugen says. “Urban planners try to protect buildings and roads by having enough drains. To do this, they need information about the weather.”

Tipping buckets

“To improve and verify their data models, we need observations that capture brief cloudbursts. It's no use measuring rainfall only twice a day,” Haugen says.

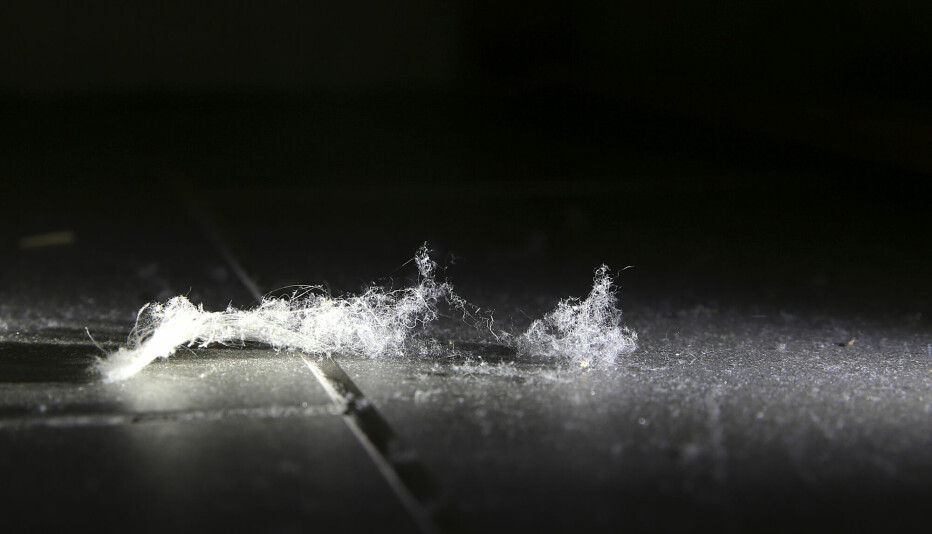

Precipitation is measured from hour to hour with an instrument called a tipping bucket rain gauge. When a certain amount of rain has filled a container, the weight causes it to tip over, triggering an electrical signal. This way, rainfall is measured continuously.

Very local events

The climate model Haugen and his colleagues are using can't predict the exact time for each rainfall. Instead, the extremely long term forecast is designed to predict how often a particular area will see powerful cloudbursts over the next 30 to 100 years, and how powerful these burst could be.

The area can be defined with great accuracy, since data is analysed very locally.

“The model distinguishes sites located only three kilometres apart," Haugen says.

One problem is that researchers can't yet predict the most powerful, and therefore most harmful, heavy rains. Since these events are quite rare, Haugen and his colleagues have not been able to collect enough data. They have more data, however, for less powerful rainstorms.

New web portal

Their results will soon be put to use by planners and others who want to avoid weather damage. In a few years they will be able to extract climate forecasts from a web portal operated by the Norwegian Meteorological Institute in Oslo, Uni Research in Bergen and the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE).

Haugen and his group will finish their report this summer. It is based on three years of research, supported by the EU project ECLISE, Enabling Climate Information Services for Europe.

In the longer term, scientists want to coordinate the climate model for extreme precipitation with the general weather models used in daily forecasts.

“With this kind of coordination, we could use the same tool for different time scales,” Haugen says. “We don't only want to provide forecasts of extreme precipitation for the distant future. We also want to make predictions for the near future.”

Reference:

The figure is taken from Ødemark et al., 2012: Extreme rainfall in south-eastern Norway from pluviometer and radar data ECLISE (Enabling Climate Information Services for Europe) project report.

--------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Lars Nygaard