Warm seas around Greenland may indicate cold European winter

Past changes in ocean currents around Greenland coincided with climate change in Northern Europe. The researchers behind the discovery suggest a possible ice-cold winter in Northwestern Europe.

A new study shows how ocean currents around Greenland have changed over the past 5,800 years.

The study also shows how, over history, periods with warm water around Southeast Greenland coincide with cold winters in Northern Europe.

“The sea south of Greenland has been very warm this summer. If the correlation between warm water around Greenland and cold weather in Europe holds true, it could indicate that we may have a cold winter in store this year,” says Camilla Andresen, a senior researcher at Department of Marine Geology and Glaciology at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS).

“Having said that, the weather is the result of a fairly complex interplay between ocean currents and differences in atmospheric pressure. But since we don’t yet have a full picture of this interplay, this is obviously merely a guess.”

The findings have just been published in the journal The Holocene.

Study of 5,800-year-old organisms

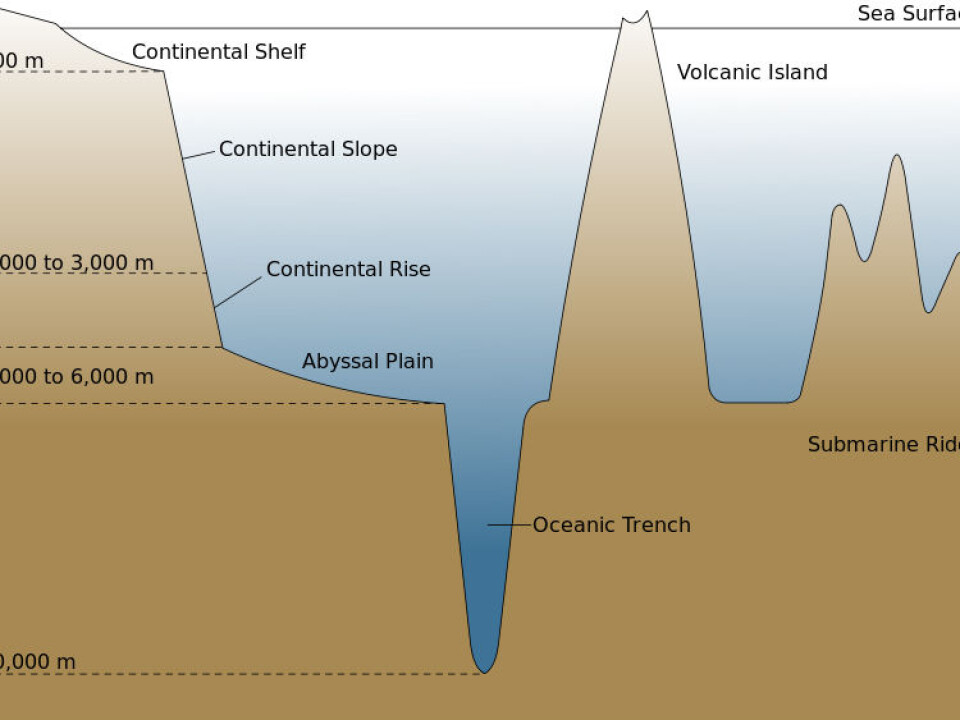

The GEUS researchers have analysed sediment cores drilled from the continental shelf off the coast of East Greenland.

In the sediment samples, the researchers have determined the species of tiny organisms known collectively as Foraminifera. Some species of Foraminifera thrive in warmer temperatures, while others prefer cold water.

Based on the species composition of the Foraminifera and radiocarbon dating of the sediment, the researchers could determine whether in a given period it has been relatively warm around Greenland as a result of increased inflow from the Gulf Stream or cold as a result of increased inflow from the Arctic.

This enabled them to create a calendar of water temperature and the strength of ocean currents in the sea around Greenland covering the past 5,800 years.

Warm water around Greenland during the Little Ice Age

Historical sources enabled the researchers to infer the coincidence between Greenland ocean currents and the Northern European weather.

The period known as the Little Ice Age, ranging from the 16th to the 19th century, is of particular interest in this context.

Historical reports indicate that the Little Ice Age had some distinctly colder winters than we do today, but the new study also shows that during this period the warm Gulf Stream travelled towards Greenland in greater magnitudes.

“The link between warm currents around Greenland and the climate in Europe partly has something to do with a weakening of the westerly winds. Instead of pulling the Gulf Stream eastwards and blowing warm winter air over Northwestern Europe, the wind system will undergo periods with a more north-south-oriented curved course,” explains Andresen.

The result is that the warm Gulf Stream is directed in greater masses westwards towards Greenland and the Labrador Sea, she adds. Meanwhile, it gets easier for cold polar air to blow into Northwestern Europe.

Ocean currents and rising sea levels

The new mapping could also become an important step towards understanding how ocean currents around Greenland affect the melting of the inland ice, and thus how much the oceans will rise during the ongoing climate change.

“The contribution from the outlet glaciers to the total ice loss from Greenland is currently one of the really hot topics among climate researchers. We know that the current contribution from the outlet glaciers makes up about half of the total ice loss from the ice sheet, but there is some debate about how this will develop in the future as the climate gets warmer,” says the researcher.

“In the latest report from the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) the contribution from the outlet glaciers is probably underestimated in the calculations of future sea level rise due to the poor quality of the outlet glacier models used at the time. So there’s a need for improved models, and that’s something our findings could contribute with.”

-------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther