A new round of hunting for instruments in the dark polar night

It is november, polar night, and almost winter – must be time for a cruise to the Arctic Ocean to collect instruments and equipment for our project!

This cruise is a bit different than most of the other Nansen Legacy cruises. We are not at sea to take the most samples possible of water and sea ice, or to catch phyto- or zooplankton, fish, or benthos. Instead, in just 11 days we want to recover and redeploy so-called moorings – installations under water with instruments anchored to the seafloor – that were set out last year or even two years ago.

These instruments continuously record things like temperature and salinity, pH, fluorescence, and other physical, chemical, and biological parameters and thus provide us with long time series of what is going on in the northern Barents Sea. Half of our group of 15 people in the science party are therefore not scientists in the conventional sense but mooring technicians, and most of the rest are their helpers.

But we will not only hunt for our equipment, we will also try and repeat some of our standard CTD transects (lines of stations in special regions) to get a snapshot of the spatial distribution of physical, chemical, and biological ocean properties in some focus regions.

Winter is here

Winter has arrived and the cold waters in the north have started to freeze over. The scientists onboard FF Kronprins Haakon are now conducting their measurements in the cold and harsh environment north of Svalbard. Air temperature is around -15 C, while the sea is in comparison warm at 0 C. The cold air is efficiently cooling the ocean though until the seawater reaches its freezing point at -1.8 C. During this process, the sea looks like it evaporates – a magical view! Once the sea surface is cold enough, sea ice starts to form.

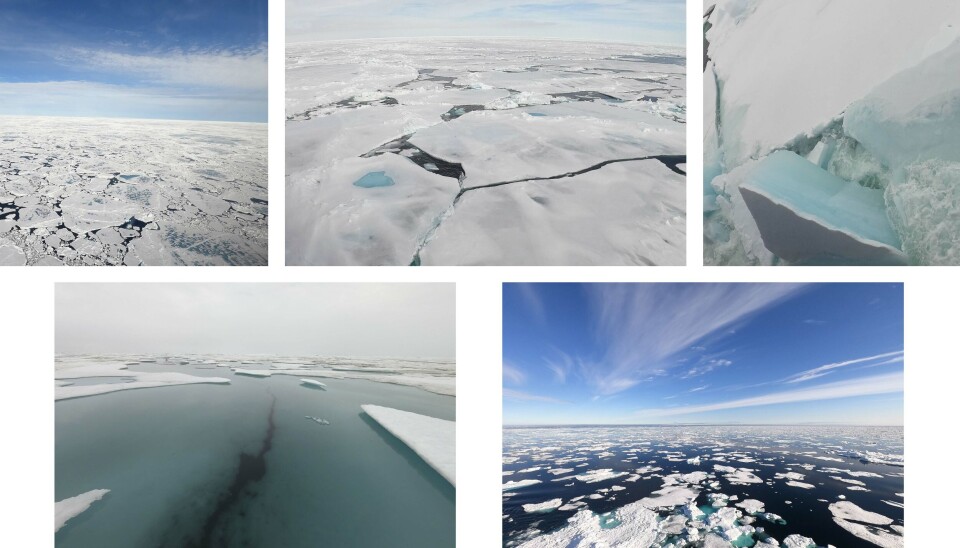

The Arctic sea ice cover varies greatly with the seasons. Each winter, large parts of the Arctic Ocean are covered by ice that can be several meters thick. In summer, much of the ice melts again. When the ice extent is at its largest in March, it covers about 15 million square kilometers, whereas in summer, the ice-covered area is only about 5 million square kilometers. Both winter and summer sea ice extent have been greatly reduced as a consequence of global warming, and the strongest reduction has been in the ice that survives the summer melt season. Since 1979 when satellite observation of sea ice started, we lost 44% of the summer ice.

When we talk about an ice-free Arctic Ocean, we mean first and foremost an ice-free summer. The latest projections suggest that the Arctic might become ice-free in summer already before 2040.

So many different types of ice

When seawater becomes cold enough, it reaches its freezing point at -1.8 C and a layer of sea ice starts to form at the surface. Did you know that there are many different types of sea ice?

New ice is an overarching term of newly formed ice. It includes frazil ice, grease ice, slush and shuga. These ice types consist of free-floating ice crystals, or crystal that are only loosely frozen together. Eventually, nilas forms. This is a thin, elastic cruise, up to 10 cm thick. It bends when waves or swell come through, and when it gets push together, if often slides over itself forming finger-like patterns (finger rafting). A different kind of drift ice is pancake ice. These pancakes are almost circular pieces of ice with a diameter of a few tens of centimeters to several meters. They have raised rims like pancakes because they collide against each other.

When the ice becomes thicker, bigger pieces like ice cakes (less then 20 m in diameter) or ice floes (up to 20 km in diameter) form. When there is a lot of ice, we often refer to ice concentration or the ice cover, and characterize the ice by its thickness. Then, we distinguish between first year ice or multiyear and old ice which has survived several summer melt seasons. This thicker ice has more of it sticking out above the sea surface and is often deformed because of ridging and rafting. Open water between ice floes is called a lead. These are just a few of the names we have to describe sea ice.

A hole in the boat!

It might sound strange, but sometimes a hole in the boat is very good and useful! On large research vessels like the FF Kronprins Haakon, we often have to do our measurements in bad weather with large waves or in ice-covered regions. Under these conditions, it can be difficult to work out on deck or deploy instruments over the side where thick ice is in the way.

The solution is then a so-called moonpool. This is an opening in the hull in the middle of the boat with large hatches that can be opened so that we can reach the water underneath. Then we can lower our instruments, underwater vehicles like our ROV, or even divers without having to make a hole in the ice.

On our cruise north of Svalbard, we use the moonpool to do CTD measurements – we lower a sonde to take water samples and measure water properties (conductivity (= salt content), temperature and depth, i.e. CTD, but also oxygen concentration, nutrients and more) from the surface all the way to the seafloor. These measurements provide us with important information for the calibration of the instruments that we recover and deploy on our moorings.

We have not disproven Archimedes principle here, so do not try to make a hole in your boat at home! But our moonpool is constructed such that its sides go high above the water line and the ship stays afloat. Do you know why it’s called “moonpool”? On open boat or oil rigs, the light of the moon is reflected in the opening and that creates the illusion of a calm swimming pool (Dr. Rutherford 1981).

How do you measure an ocean current?

Our moorings do not only measure temperature and salinity, they also listen after the ocean’s movements! We can’t hear ocean currents – or can we? Ocean scientists are very interested in currents because they influence life in the water as well as weather and climate on land. But measuring the strength and direction of a current is not so easy. Our moorings measure the inflow of warm Atlantic water that is entering the Arctic Ocean from the south, through Fram Strait along the west side of Svalbard. This warm water and the strength of this current influence among other things how much ice is melting where we are now and how far north different species thrive. The moorings are equipped with so-called ADCPs (Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers), instruments that use acoustics to measure current strength and direction.

The ADCP send out an acoustic signal with different frequencies, which then gets reflected by bubbles and particles in the water. The reflected signal that reaches the instrument has a slightly different frequency than the original one because of the Doppler effect, and with a bit of maths and trigonometry, we can calculate the velocity of the particles. We do this for different depths and over time and with that get an overview of the current and its temporal changes. So in a way, we can hear the strength of a current! We have now deployed several new ADCPs in this cold and dark polar night, and hope to find them again in the same location next year.