Two birds have cheated scientist for decades

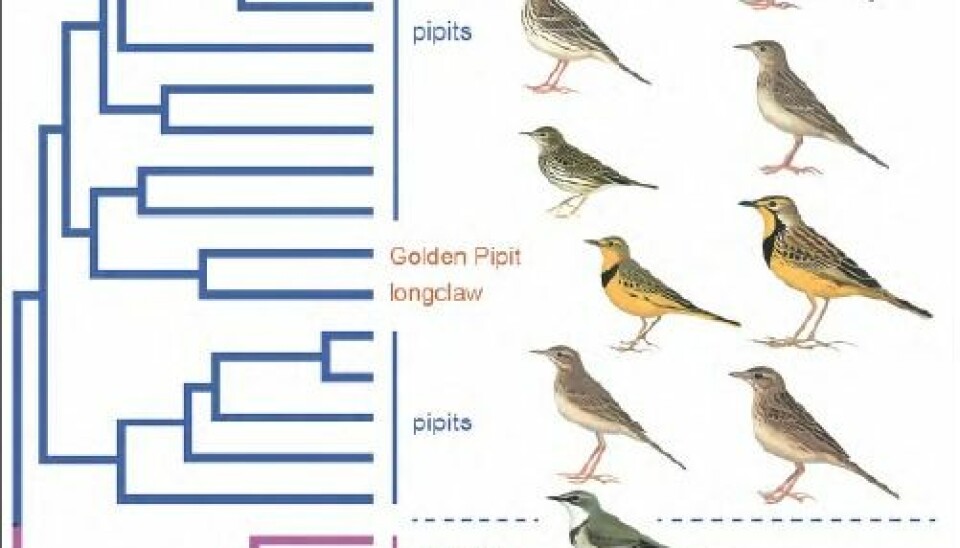

Scandinavian scientists have turned the family trees of two birds upside down using genetic analysis.

Scientists thought they knew all there was to know about the tree pipit and the wagtail, two small birds who look nothing alike and behave nothing like each other. How wrong those scientists were.

In fact, the genetic origins of the two birds are completely different from what scientists assumed and the two birds are actually very closely related, writes the Centre for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate at the University of Copenhagen in a press release.

Collaboration between Danish and Swedish scientists have shown that the Madanga or Rufous-throated White-eye (Madanga ruficollis), which flutters about on the Indonesian island of Buru, is not closely related to other spectacled birds. It is instead related to the tree pipit -- a common sight in Northern Europe during the summer.

This is remarkable, since the bird doesn't in any way resemble the more than 40 other members of the Motacillidae family which includes pipits and wagtails.

In fact, nothing about its appearance or behaviour is like its distant cousins who all scurry about on the ground.

"Only a single individual was seen, although it was immediately obvious that it did not behave like a spectacled bird. We therefore decided to examine the DNA from three old specimens of the birth," says Professor Jon Fjeldså from the Centre for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate at the University of Copenhagen in a press release.

Island life gave it a new appearance and new behaviour

The study, just published in Royal Society Open Science, also shows that the relatively unknown Bocage's Longbill (Amaurocichla bocagii) from the island of São Tomé in the Gulf of Guinea off West Africa, is a wagtail.

The bird's family tree has been under discussion for some time. Neither its plumage nor its body shape are similar to other wagtails.

"We assume that both birds have developed differently in relation to their close relatives because their forebears flew out and colonised forest-clad tropical islands, while their relatives live in particular in open grassy landscapes on the mainland," says Fjeldså. “This brought about fundamental changes in their food and habitat, to which the birds have adapted themselves, cheating science for decades.”

---------------

Read the original story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Hugh Matthews