CRISPR breakthrough ignites hope of using pigs as organ donors

Scientists have effectively switched off virus genes in pig DNA, bringing us one step closer to using pigs as organ donors for humans.

Scientists have overcome one of the two major hurdles for transplanting organs from pigs into humans.

Specifically, they have switched off some of the virus genes in pig DNA, which have so far prevented us from transplanting, for example, a pig’s heart into a human.

The breakthrough is an important step towards preventing death among people waiting to receive a new heart, liver, or kidney.

“By switching off the virus genes, we’ve removed the risk of viral infections introduced from the pig’s organs to humans after a transplant. This is a big medical problem that we need to solve in order to use organs from pigs in people,” says co-author Yonglun Luo, an associate professor at the Department of Biomedicine, Aarhus University, Denmark.

The new results are published in the journal Science.

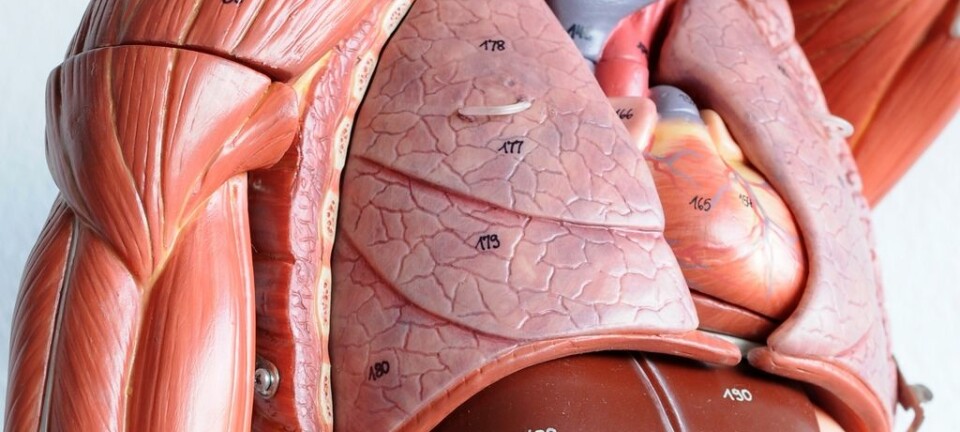

Pigs can supply hospitals with organs

Pig organs match human organs in terms of function and size, which means they could supply hospitals with a never ending stream of hearts, lungs, kidneys, livers, and more.

But before doctors can transplant organs from pigs into people, scientists need to solve two problems.

First, they need to solve the immunological problem of our bodies rejecting the pig’s organ because the immune system attacks it.

Second, all organisms contain virus DNA in their genome, so if a human receives a heart from a pig, this virus can become a part of our genetic material and potentially introduce dangerous diseases such as cancer.

The virus genes can also hijack the cells’ genetic machinery to produce more viruses, which can circulate around the body and make us ill.

It is the second problem that scientists have now solved with the gene-editing tool, CRISPR.

“We’ve switched off the porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERVs) in the pigs, so that the PERVs can no longer replicate itself and infect people,” says Luo.

Greater perspectives in applied technology

Scientists still have to solve the problem of how our immune system reacts to organs from another animal, but the study is a big step towards transplanting animal organs into humans, says Bente Jespersen, a clinical professor in kidney diseases at Aarhus University.

It also solves a problem of infections between people, she says.

“The applied technique [CRISPR] has bigger implications and if what the study suggests is true, then it could perhaps completely remove the large risks associated with these viruses that can be passed on from the transplant patient to other healthy people,” says Jespersen

Luo and colleagues are already looking into how CRISPR can be used to solve the compatibility issue. He estimates that it will require modification of at least 28 genes on top of the virus genes, and that it will take a couple of years before large and complex organs like the heart and liver can be transplanted from pigs into humans.

“But smaller organs like skin, insulin-producing cells or corneas might be available earlier,” says Luo.

----------------------

Read more in the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex