Scientists zoom in on neck and shoulder pain

Researchers have developed a method for measuring changes in the central nervous system caused by neck and shoulder pain.

Today’s sedentary lifestyle has greatly increased the number of cases of neck and shoulder pain.

These pains, known collectively as musculoskeletal disorders, are difficult and expensive to treat, partly because scientists have yet to fully understand the underlying mechanisms.

But now, researchers at the Center for Sensory-Motor Interaction (SMI) at Aalborg University, Denmark, have come one step closer to understanding neck and shoulder pains and how they arise.

Using a ground-breaking training tool, developed by SMI researchers, PhD student Steffen Vangsgaard and Professor Pascal Madeleine have developed a method for measuring the activity in the trapezius muscle. This activity says something about how the muscle communicates with the central nervous system (CNS) by means of electrical signals.

“This methods allows us to identify changes in the CNS related to the neck/shoulder region, and this may perhaps be used for diagnosing and monitoring the effect of the treatment of neck/shoulder patients,” says Vangsgaard.

Controlled pain simulation

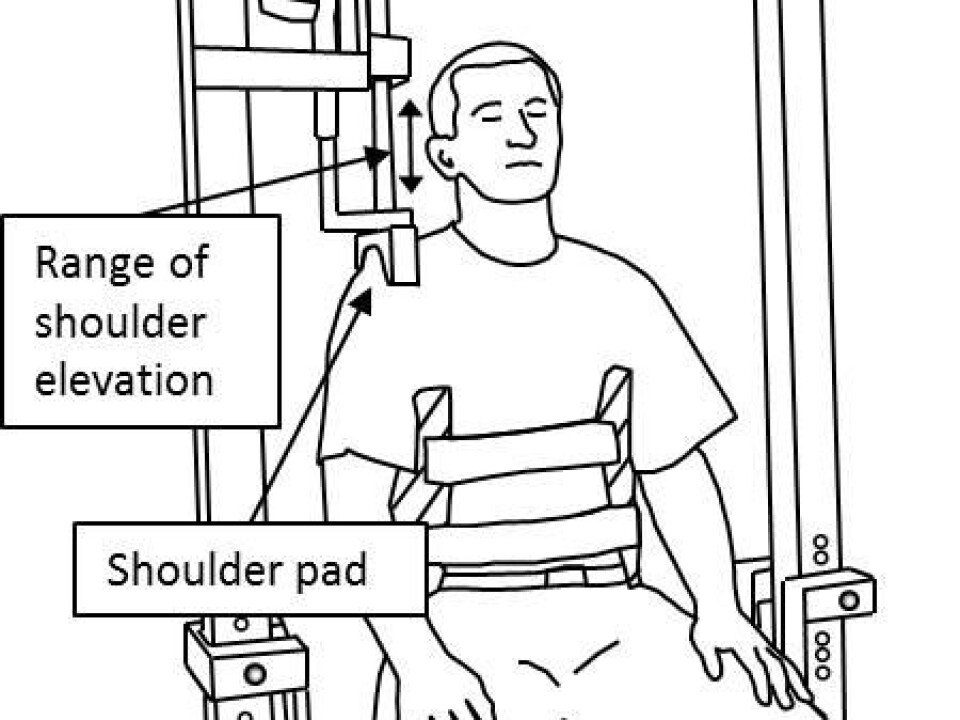

To chart the changes that occur in the CNS in relation to shoulder pains, the researchers used a specially designed training tool, known as a ‘Shoulder Dynamometer’.

This dynamometer works by placing a subject in the seat, wearing a corset. The exercise in the study consisted of bilateral shoulder shrug movements to counteract the force of a descending shoulder pad.

Once the movement has been completed, the shoulder pad goes back into the top position, without the subject having to press it upwards.

This ensures eccentric shoulder movements only – i.e. movements that stretch the muscle. This type of physical activity has been found to cause the same type of aches and pains as those experienced by neck/shoulder patients.

”That’s why the shoulder dynamometer can be used to simulate the pain under controlled circumstances,” says Madeleine.

Study confirms advantages of the method

The team from Aalborg University has been working with colleagues from Neuroscience Research in Australia to develop a method that by measuring changes in the CNS helps them assess how aches and pains in the shoulder region affect this system.

”We measured before and after the eccentric movements performed in the shoulder dynamometer and we observed a significant reduction in activity between the CNS and the muscle,” says Vangsgaard.

”The study thus confirms the potential of using examinations of the CNS in connection with the diagnosis of muscle pain.”

Stronger muscles reduce pain

But although the researchers have now found an apparent correlation between changes in the CNS – where the signalling between the muscle and the CNS changes – and pain, there is still some way to go before this information can be transformed into improved diagnoses and treatment.

”Since we observed changes after the eccentric movements, which simulate neck/shoulder pains, it is now important to examine whether eccentric training can have a preventive effect on healthy people before we start using the exercises for people with neck and shoulder pains,” says Madeleine.

According to the researchers’ hypothesis, the preventive effect occurs because eccentric exercise strengthens the muscles that cause pain and enables them to use the muscles more efficiently. Various studies have shown that eccentric exercise counteracts pain, but the researchers do not yet know why this is so, or how much eccentric exercise is needed.

Testing on healthy subjects

For this reason, the researchers are currently studying the effect of eccentric exercise on healthy research subjects.

”We’re testing healthy people, partly to prove our hypothesis, and partly to measure the effect of the exercise before it’s used on people with actual pains,” says Vangsgaard.

This is an eight-week trial in which subjects are divided into two groups. One group performs eccentric exercises in the shoulder dynamometer, while the other does not.

Can the pains be prevented?

The researchers will then be using the refined method to measure the signalling between muscles and the nervous system, and if there is an increase in the signalling, it indicates a preventive effect.

“We know that people who perform eccentric exercises experience an initial reduction in the signalling between the muscles and the CNS, but once they are accustomed to the exercise, the signalling returns to normal and the pain-like soreness disappears. We’re studying whether further exercising can increase the signalling and thus prevent neck and shoulder pain,” says Madeleine.

The study is published in the European Journal of Applied Physiology.

----------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk