New method measures CO2 production of sub-seabed bacteria

A new method for measuring the activity and CO2 production of sub-seabed bacteria could offer new knowledge about the long-term effects of sub-seabed bacteria on the climate.

Microbiologists have developed a new method for measuring the activity of bacteria found so deep below the surface of the seabed that it has previously been impossible to perform such measurements.

The results provide a valuable insight into the effects of sub-seabed bacterial activity on global carbon dioxide emission and ultimately to the atmospheric oxygen-levels.

“It has previously been proved that bacteria found in the seabed convert organic material into CO2 and that these processes play a key part in the global carbon cycle”, says Bente Lomstein, a lecturer in microbiology at the Department of Bioscience at Aarhus University.

Lomstein is a member of the team of researchers behind the new method, which has been developed in collaboration with the Danish National Research Foundation’s Center for Geomicrobiology and researchers from the University of Rhode Island, USA.

Until now measuring exactly how significant these processes are has been impossible. In the long term, this new method may prove instrumental in making it possible.

The new method might pave the way for further progress in the field, as Lomstein points out:

“Until now measuring exactly how significant these processes are has been impossible. In the long term, this new method may prove instrumental in making it possible.”

Lomstein is part of the team of researchers behind the new method, which has been developed in collaboration with the Danish National Research Foundation’s Center for Geomicrobiology and American researchers from the University of Rhode Island, USA.

Bacteria make up 10-30 percent of Earth’s biomass

The vast influence that microorganisms have on the climate is due to the fact that an astonishing 90 percent of Earth’s microorganisms are found in the muddy seabed.

In fact, since 70 percent of the Earth’s surface is covered by water, the microorganisms make up between 10 and 30 percent of the Earth’s total biomass.

The microorganisms feed on the mud, which consists of deposits of old organic matter which in some places reaches a thickness of up to one hundred metres.

“The bacteria in the seabed convert the carbon in the organic matter into CO2, and when we start adding it all up, the conversion that goes on down there plays a key part in the global carbon cycle – even though it all happens very slowly”, explains Lomstein.

It takes a single sub seabed bacterium between 1,000 and 3,000 years to split. This is an extremely slow process compared to many other bacteria in nature, or in laboratories, where the multiplication process only takes hours.

For these reasons, the deep seabed has long been an area where the methods available to scientists have only facilitated a very limited measurement of the CO2 production of microorganisms.

However, the new method will allow scientists to reach down to 200 metres below the surface of the seabed, accessing organic matter as old as ten million years.

In the long term, the method will allow scientists to make accurate calculations of the levels of activity in the seabed and the effects this will have on the global climate.

Estimation of the CO2 emission calls for further measurements

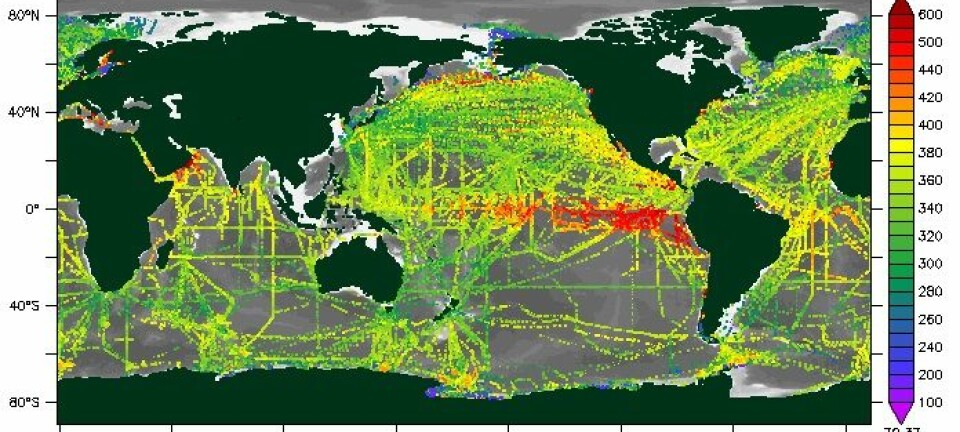

Up until now, scientists have examined samples from the seabed 5,000 metres below the surface of the Pacific, off the coast of Peru.

Nevertheless, as the researcher points out, further tests are needed in order for the method to secure useful results:

“This is only a small piece of a large puzzle. We now have the method, but we need to collect data from many other locations around the world with different conditions in order to arrive at an estimate of the extent to which microorganisms contribute to the global carbon cycle and thus affect the climate”, Lomstein concludes.

----------------------------

Read this article in Danish at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Iben Thiele