Why interval training can lead to better conditioning

And why not everyone gets the same amount of benefit from a hard workout.

It’s generally known that high intensity interval training can have an effect on physical performance. But in a cruel twist of biology, the most well-trained athletes appear to see the least benefit from this training technique.

Researchers from several Swiss universities and the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden, among others, have now uncovered one reason behind this seeming paradox, a secret deep inside our muscle cells.

Not an exercise study

Jostein Hallén is head of the Department of Physical Performance at the Norwegian School of Sport Science who was not involved in the study.

He says it is important to keep in mind that the study did not test the effectiveness of different kinds of workouts, but instead was looking at possible mechanisms to explain how high intensity training might work.

“The study says nothing about whether high-intensity exercise is effective or not. It was looking for the mechanisms behind this kind of training and proposes a mechanism,” he said.

High intensity interval training

The researchers who did the study used what is called high intensity interval training (HIIT) in their experiments. HIIT is one of the hottest forms of exercise right now, both literally and figuratively.

HIIT ranks near the top of the top-20 list of fitness trends for 2015 on the website trening.no.

HIIT is also hot in the physical sense. You must push yourself as hard as you can for short intervals, close to your maximum heart rate, with short active periods of “rest” between each interval.

This type of exercise has been popular because it can be very effective without requiring a big investment of time.

Least effect for best trained

The study, published in the Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), was conducted with two groups of young men who were asked to push themselves to their limit in an HIIT workout on a stationary bicycle.

One group was made up of men who only trained in their spare time. The second group was made up of highly trained elite endurance athletes.

The study found, however, that only recreational athletes experienced changes in their muscle cells after the HIIT workout.

To understand why requires a quick lesson in how our muscles actually work.

Calcium plays key role

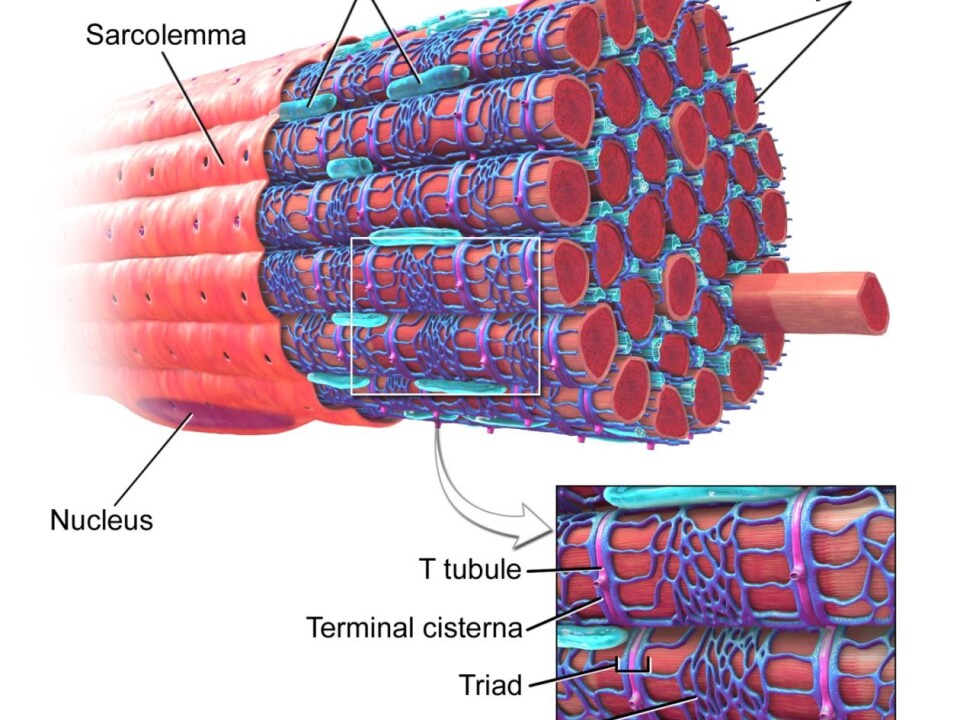

When the nerves tell a muscle cell to contract, the cell is flooded with electrically charged calcium atoms - calcium ions. These ions cause the muscle to contract.

The problem is that when the muscle works really hard, the effort causes problems with its calcium supply.

Under hard training, instead of a controlled release of calcium to tell the muscle to contract, followed by no calcium release when the muscle should relax, there is leakage of calcium all the time. The muscle cell never gets to really relax.

The body responds to this stress by making more mitochondria, which are popularly known as the power supply for the cells. That means the muscle has more energy available for a longer period of time, which boosts endurance.

The research published in PNAS suggests that top athletes don’t see this boost in mitochondrial production – and hence the boost in endurance – because over their many hours of training, the muscles of elite athletes have “learned” how to handle the stress and don’t leak calcium.

Not such a time-saver after all

Hallén, for one, thinks perhaps that the benefits of high-intensity interval training may be exaggerated, at least when it comes to saving time.

He says that even though the actual intense periods of exercise go quickly, you still have to warm up and stretch after your session.

“When you include your warm-up, the rest periods between intervals and stretching afterwards, this type of training take as long as other types of training,” he says.

He also points out that moderate training over longer periods can result in the same beneficial effects.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no