Scientists: Rewilding is a Pandora’s box

Scientists speak out against rewilding projects, where lost species are reintroduced into the wild.

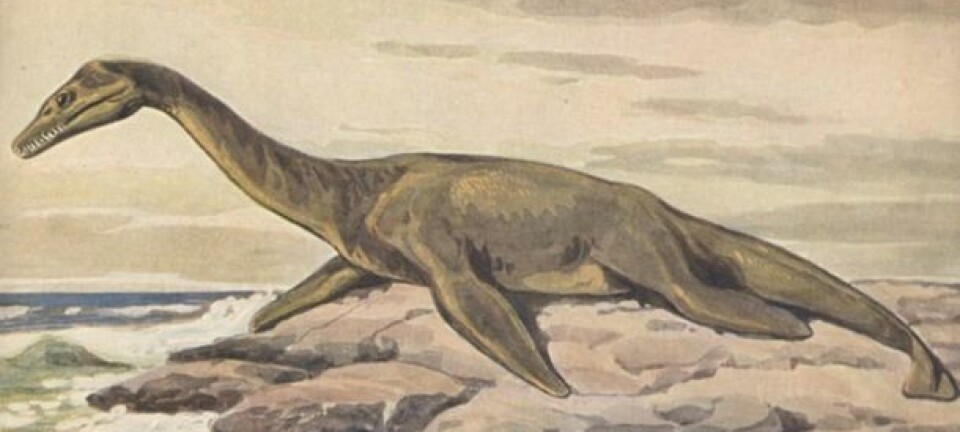

The reintroduction of large mammals like beavers, bison, and even elephants into areas where they had become extinct, has been gaining traction around the world.

Rewilding is the name of the concept, and the idea is that the animals will have a domino effect on their surroundings, which will help restore diversity in nature and provide people an opportunity to experience these animals once again.

But not everyone is behind this project, and a group of researchers are now speaking out against the trend in an article published in the scientific journal Current Biology.

They refer to rewilding as a 'Pandora's box' and they warn that there is no, or only very weak, evidence for its beneficial effects.

On the other hand, they write, there are plenty of historical examples of disastrous, unforeseen consequences associated with introducing species to new places.

"Scientifically, we’re floating around in the dark in terms of what the consequences of rewilding will be, and we’re very concerned about the general lack of critical approach around this type of nature management, which is often also extremely expensive," says co-author Associate Professor David Nogués-Bravo at the Center for Macroecology, Evolution, and Climate, at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

The risks of rewilding are exaggerated

Professor Jens-Christian Svenning from Aarhus University, Denmark, is a supporter of rewilding.

“It’s totally correct that there are far too few scientific studies [on the effects of rewilding], but I think they’re exaggerating the risks,” says Svenning.

But according to Nogués-Bravo and colleagues, there are many examples in history where introducing new species into an ecosystem had detrimental effects, which were difficult to reverse.

One example is the brown tree snake on Guam in the western Pacific, which destroyed almost all the birdlife on the island after being accidently released into the wild.

Another example is the Canadian beaver, which was introduced in Tierra del Fuego at the southern tip of South America to kick-start a fur trade. The latter did not work out, but the beavers successfully spread into Patagonia in Argentina and Chile, where they created huge economic damage.

Svenning is not persuaded by such arguments

“This is all true, but these are examples of species and functional types that had never previously existed in these areas. This wouldn’t happen today,” he says.

Rewilding reintroduces animals into their natural habitats

According to Svenning, rewilding should reintroduce species to their natural breeding areas, where there are similar species with the same ecological function.

"But of course you have to follow it up with research," he says.

One of the most famous examples of rewilding is the reintroduction of wolves into Yellowstone National Park in the US. It worked, and scientists have observed a positive cascade effect on the park’s landscape, where plants have sprung up again in areas where deer no longer go, in an effort to avoid being eaten by a wolf.

Despite this famous success story, Nogués-Bravo and colleagues estimate that seventy per cent of rewilding projects ultimately fail.

They stress that the ecosystems are complex, and that it is extremely difficult to predict the consequences of releasing new species into the wild.

-----------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex