Gravitational wave discovery was most likely a measurement error

New analysis from the European Planck satellite suggests the physicists underestimated influence of cosmic dust.

When the US research group BICEP2 announced in March this year that they had measured signals from gravitational waves -- reaching all the way back to the beginning of the Universe -- there was much excitement.

The excitement, however, has waned now, after the initial results have been scrutinised be physicists from the rest of the world.

A new study with participation from Danish scientists suggests the BICEP2 team underestimated the significance of cosmic dust in their measurements. This has provided critics, who remain unconvinced gravitational waves were measured, with new arguments.

"The discussion isn't over yet,” says Hans Ulrik Nørgaard-Nielsen, senior researcher and astrophysicist at DTU Space. “Although, we certainly can say that some of the signals measured by BICEP2 come from cosmic dust.”

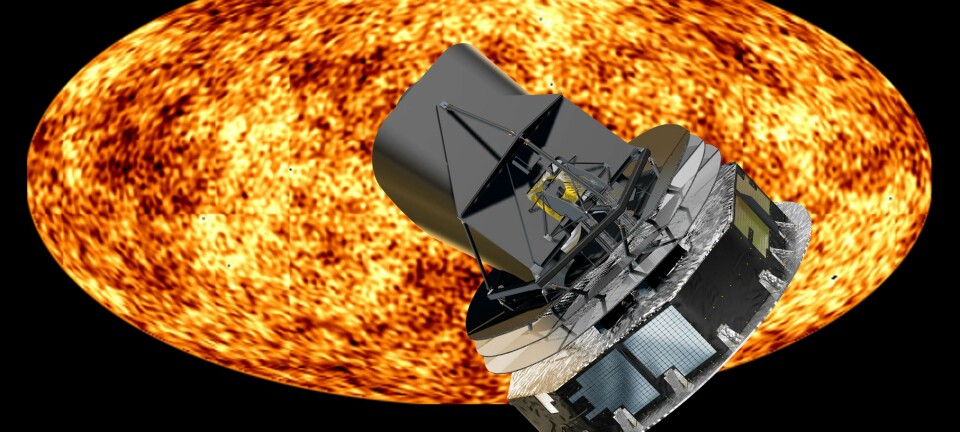

Nørgaard-Nielsen is one of the physicists behind the new study based on data from the European Planck satellite.

Measurements tell us about the birth of the universe

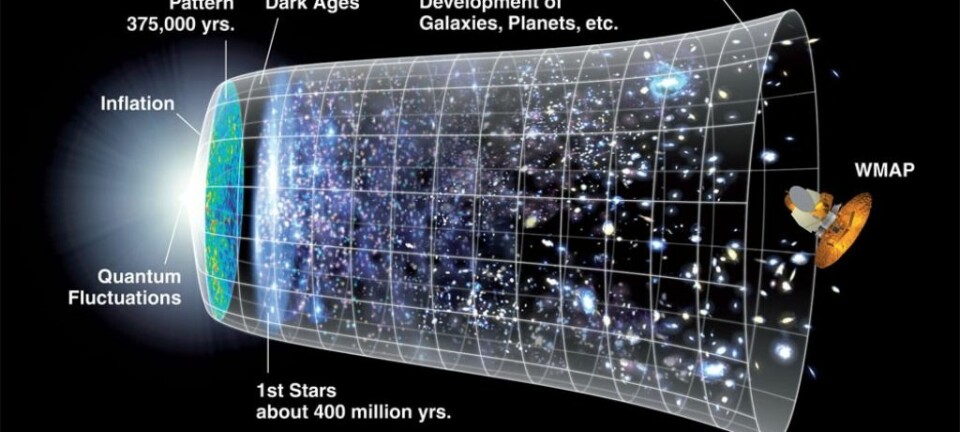

When the BICEP2 researchers published their measurements earlier this year they were seen as a tremendous breakthrough because they were the most direct evidence to support the theory known as 'cosmic inflation' ever reported.

Cosmic inflation is a phenomenon which occurred split seconds after the birth of the universe -- the Big Bang -- causing the Universe to expand at a colossal rate.

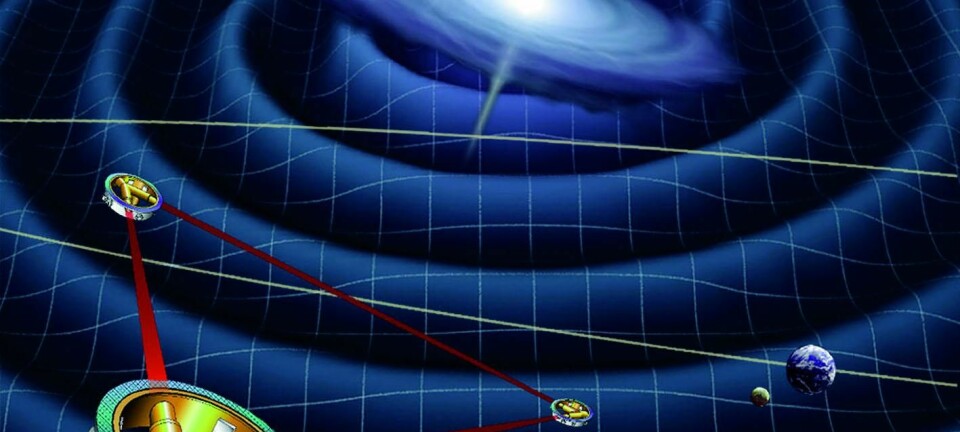

The cosmic inflation theory involves an extremely precise prediction that so-called gravitational waves -- ripples in space time -- would be created. This is also described as the 'the first tremors of the Big Bang'.

According to the theory, these gravitational waves would leave behind a specific pattern in the oldest light in the sky, the cosmic background radiation.

It was this pattern the BICEP2 physicists believed they had been able to measure using a large telescope located on the South Pole.

"You can't actually see gravitational waves, but it should be possible to measure the impression they make on cosmic background radiation,” says Nørgaard-Nielsen. “The problem is, however, that it’s one hell of a weak signal so it can easily be polluted with all sorts of error measurements.”

Dust could be a cause for error

In their new analysis, the European Planck satellite team discovered that the BICEP2 scientists had underestimated how much cosmic dust there is in our own galaxy, the Milky Way.

This might’ve affected their results.

"Since these measurements are extremely difficult to make we can only conclude that BICEP2 has underestimated the amount of dust,” says Nørgaard-Nielsen. “By just how much they’ve underestimated it, we don't know yet.”

At the same time it can’t be excluded that BICEP2 did indeed see gravitational waves.

“There’s a possibility that they’re right,” says Nørgaard-Nielsen. “They may well have measured signals from the Big Bang -- but if they have then they’ll be weaker [than what has been reported].”

'Extremely important' to our knowledge of the birth of the universe

Associate professor Martin Sloth from the Department of Physics, Chemistry and Pharmaceutics the University of Southern Denmark agrees.

"Whereas BICEP2 previously claimed to have observed gravitational waves, Planck now shows us that this is not necessarily true. They can't exclude it being true, but they can show that BICEP2's measurements could be due to the effect of cosmic dust," says Sloth.

He studies the origins of the universe but was not involved in the new study.

"This is extremely important,” says Sloth. “If BICEP2's results were correct, they’d have extreme consequences for our knowledge of the birth of the universe.”

Planck expected to clarify

The Planck team is expected to publish new results later this year which will further clarify what BICEP2 actually saw.

In addition to this, a group of BICEP2 and Planck physicists have joined forces to get to the bottom of the dispute. And settle if the observed signals are indeed remnants from the creation of the Universe some 13.8 billion years ago.

Nørgaard-Nielsen says collaboration is the logical thing to do.

"BICEP2 had problems working out how much dust there was in their measurements and the Planck satellite is specially constructed to describe signals from cosmic dust,” he says. “So it was a good idea to join forces and try and achieve a better result.”

The new results from Planck should be ready for publication in December this year.

---------------------

Read the original story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Hugh Matthews