Researchers' Zone:

Our attention span is shorter than ever before. What are the consequences?

Get the explanation as to why we are so bad at concentrating for an extended period of time... That is, if your attention span goes that far.

“Thou shalt commit adultery!”

Such was the command in a large number of copies of the Bible from 1631, where a printing error snuck into the 7th commandment.

The Archbishop of Canterbury was ready with an explanation as to what had gone wrong: lower paper prices and faster printing services had led to anyone being able to print books, and no one took the time anymore to do it properly.

So, the concern about what modern technology does to our attention span has a vast history behind it.

In our research, published in Nature Communications, we present for the first time a method of measuring how our collective attention develops over time.

We did that by looking at, for example, hashtags that represent topics of conversation on Twitter. By examining popular hashtags, we were able to calculate the timespan from when a hashtag is used for the first time until it reaches its maximum popularity, and then until people stop using it again.

By analysing 43 billion tweets on a supercomputer, we found firm indications that we are collectively interested in topics for shorter and shorter periods of time.

Looking at how long a new, popular hashtag can be found among the top 50 most used, we found that the timeframe went down from 17.5 hours to 11.9 hours in just three years.

Imitation, competition, obsolescence

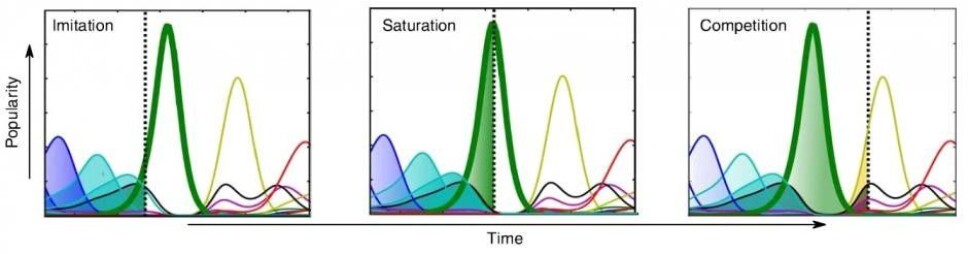

In an attempt to describe the evolution of our attention mathematically, we borrowed a model from evolutionary biology that describes how different species – for example, rabbits and foxes – compete with each other over a shared, limited resource.

In our case, rather different subjects compete for a limited resource – our attention.

The model considers three things:

- Imitation: Just as rabbit populations grow, imitation leads to an expansion of popular topics. This effect allows topics to achieve huge viral popularity quickly.

- Competition: Just as large numbers of foxes make it harder for rabbits to thrive, it is harder for a subject to catch our attention if there is fierce competition from other interesting topics. This allows the 'silly season' effect – if there is nothing else of interest in the ether, an otherwise boring topic may end up attracting a fair bit of attention.

- Obsolescence: Finally, we added an effect that describes how we find subjects duller the more we engage with them. This effect describes how we quickly become bored with a topic if we read a lot about it.

Not only does the model provide a good description of our activity on Twitter over short periods of time, but, by taking into account that we produce tweets faster and faster, the model also explains how less and less time elapses before we find a topic to be boring.

The attention we can afford a certain topic is simply exhausted faster, which means a shorter collective attention span.

Our attention is wavering - but not everywhere

The phenomenon is not unique to social media.

We carried out similar surveys for other domains – for example, we analysed data from ticket sales for cinemas, google searches and books, all of which showed the same trend: popular movies, books and 'google words' are popular for a shorter period of time now than three years ago.

So perhaps the Archbishop of Canterbury was onto something.

However, there were also exceptions to the rule. We did not find that there was 'attention acceleration' in our consumption of Wikipedia entries and scientific articles. Common to both is that we typically use scientific articles and Wikipedia to obtain information on a specific topic.

These are not, therefore, areas where topics are in fierce competition for our attention.

Information overload creates a short attention span

In short, we have thus found strong evidence that our collective attention spans are becoming ever shorter in a number of areas.

We have created a mathematical model that uses imitation, obsolescence and competition between topics to provide a good description of our attention within a variety of domains such as Twitter, feature films and books.

By allowing the model to take into account the fact that information is produced faster and faster as time progresses, it describes precisely the development we are seeing – that our collective attention becomes shorter and shorter as time progresses.

The model thereby indicates that this development is caused by us being presented with more and more information that we have to process.

The increased production contributes to increased competition for our attention; to better conditions for individual topics to quickly grow viral; and to the fact that we perceive a topic as obsolete more quickly.

Small matters can deter our attention from important topics

We hope that our results can raise awareness of our consumption of news in particular.

We are increasingly consuming news digitally, and competition for our attention is fierce. For example, we know that fake news spreads more and faster than actual news.

What does it mean for the media landscape if fake news not only reaches us first but also exhausts our attention for the subject so we don't bother reading actual news afterwards?

Our findings also suggest that we should take care not to squander our limited attention when it comes to important issues.

An example would be when the Danish finance bill, including the controversial Lindholm Centre, was passed in December 2018.

The day before the finance bill was to be passed, a two-year-old ‘infringement case’ appeared in the media, and both politicians and citizens eagerly shared the story of 'the Danish song is a young blond woman'.

When the finance bill was passed shortly afterwards, both media coverage and reactions on social media were somewhat subdued – the infringement case had won the competition for our attention.

Translated by Stuart Pethick, e-sp.dk translation services. Read this version in Danish at Videnskab.dk’s Forskerzonen.

References

Bjarke Mønsteds profil (LinkedIn)

'The spread of true and false news online'. Science (2018) DOI: 10.1126/science.aap9559f