NASA spots smallest planet ever

NASA's Kepler space telescope has found the hitherto smallest of all known planets beyond our Solar System. It’s as small as our own Moon.

A team of Danish astrophysicists has now made what may well be a sensational discovery. They have found the smallest planet that has ever been observed in orbit around a star other than our Sun.

With a radius of only 0.3 times that of the Earth, the planet orbits its host star once every 13 days.

Kepler-37b, as it has been named, has two siblings, c and d, which with radii of 0.74 and 2 times the Earth’s radius are also quite small.

The faint Kepler-37 star and its three small planets are estimated to have been created some six billion years ago.

More small planets than we thought

This provides us with a much clearer picture of how many small, medium-sized and large planets there are out there. It also teaches us a lot about how typical and atypical solar systems are put together.

The discovery of the little planet and its cosmic neighbourhood was made by a group of Danish astronomers, who have analysed data from NASA’s Kepler space telescope.

“This discovery is interesting on two accounts,” says astrophysicist Lars A. Buchhave, of Copenhagen University’s Niels Bohr Institute.

“Firstly, it is almost inconceivable that it should be technically possible to discover something as small as this planet. Secondly, it shows that when we do manage to find such a small planet against all the odds, the universe must contain many more of these tiny planets than we thought,” he says.

“This provides us with a much clearer picture of how many small, medium-sized and large planets there are out there. It also teaches us a lot about how typical and atypical solar systems are put together.”

Telescope on the lookout for eclipses

We estimate that a typical planetary system has many of these small planets orbiting around them.

The Kepler space telescope discovered the planets thanks to a trick that exploits the fact that a star is eclipsed when a planet passes in front of it.

By observing the star over a longer period, the telescope has detected rhythmic dips in the star’s brightness, which occur whenever a planet has completed an orbit around the star. The strength and duration of these dips depend on the size and the orbital period of the planet in question.

These dips contain information about the planet that caused them – including the type, size and how closely it orbits around its parent star.

Like looking for a needle in a haystack

If the Kepler-37b planet had orbited one of the many other stars that the Kepler telescope is observing, it would probably have been impossible to detect.

This is because the dips in the star’s brightness, caused by the gravitational tug of the orbital planet, are so tiny that they would probably have drowned in noise.

Detecting the eclipse from a planet as small as this one would only be possible for about a half percent of the stars featured in Kepler’s observation programme. Out of a total of 150,000 stars, it’s only possible to detect tiny planets like Kepler-37b orbiting around 700 of them – and that’s assuming that their orbit enters Kepler’s line of vision.

It is therefore statistically highly unlikely that it’s possible to detect such a planet unless there are many of them in the universe. And since Kepler has now discovered such planet, the astronomers firmly believe that there are many more such planets out there.

”We estimate that a typical planetary system has many of these small planets orbiting around them,” says Hans Kjeldsen, of the Stellar Astrophysics Centre at Aarhus University.

Moons can support life

The rocky planet is unlikely to have an atmosphere and thus cannot support life as we know it.

Planets of this size are far from ideal for harbouring life because their gravitational fields are too weak to sustain a protective and life-giving atmosphere.

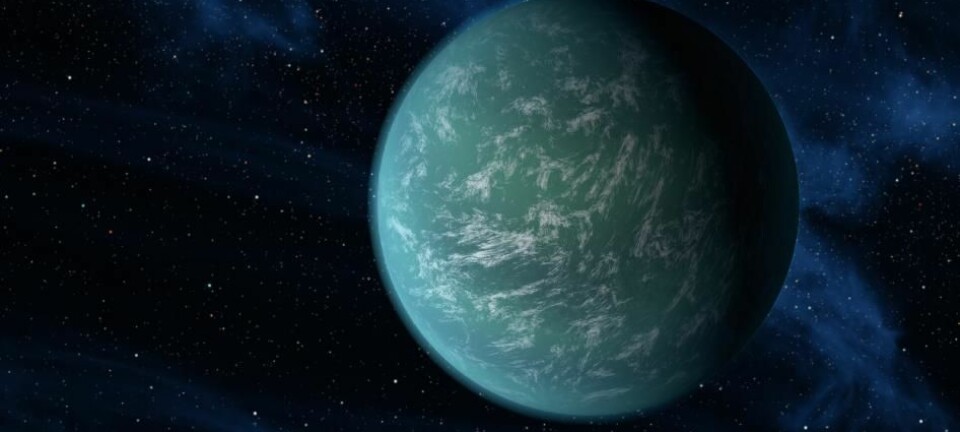

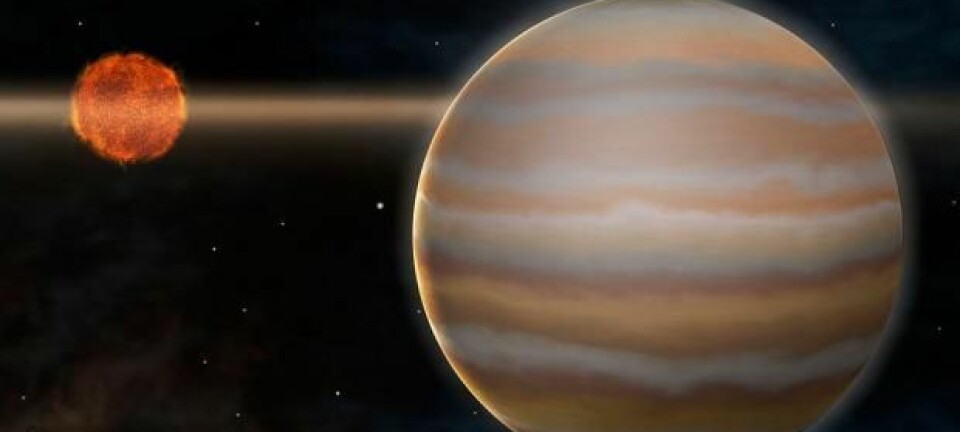

Giant planets like Jupiter would not be suitable for life either, even if they are located within the so-called habitable zone. This is because they lack a solid surface.

However, such gas planets may very well have a rocky moon the size of Earth, which has an atmosphere and a surface that can contain liquid water.

The search for such moons is well under way with the HEK research project – The Hunt for Exomoons with Kepler – with which Buchhave is deeply involved.

“We have yet to find such moons,” he says. “But now that we can see planets that are as small as Earth’s Moon, we are optimistic that we will find something in the near future.”

------------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther

External links

- Lars A. Buchhave's profile

- Hans Kjeldsen's profile

- About the Kepler mission

- About exoplanets (Wikipedia)