The sound of one hand singing

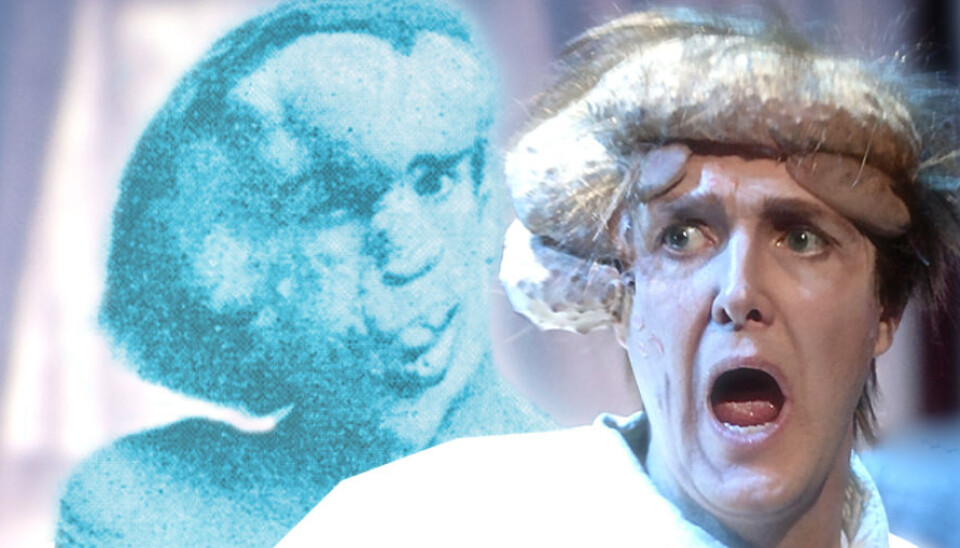

The tragic story of the Elephant Man was recreated for opera with the aid of an electronic musical glove.

How do you write and stage an opera about a man who can scarcely talk, let alone sing?

“The Elephant Man had a disfigured hand. Our electronic hand recreates these deformations musically,” says Carl Unander-Scharin, who played a key role in developing the high-tech glove and also composed the opera.

A tragic life and un-operatic sounds

The Elephant Man's real name was Joseph Carey Merrick, who was born in Britain in 1862. Merrick had a condition that caused his head, face and half of his body to be deformed by folds of skins and warty growths. Scientists still don't know exactly what caused his severe deformities.

Tenor Håkan Starkenberg played Merrick in a production by Swedish opera company Norrlandsoperan in the autumn of 2012.

Using a glove developed by Unander-Scharin called “The Throat III”, Starkenberg could change the tone by moving his wrist, index finger and middle finger.

The electronic globe was remotely connected to a computer that recreated the un-operatic sounds of phlegm, a wheezing infection and a cough.

“(The glove) creates a raspy, machined tone out of Starkenberg’s voice: irritating to start with, then more and more fascinating,” wrote a Swedish theatre critic. The production was a success, Unander-Scharin says.

Deemed an idiot

The Elephant Man made his living as the star attraction of freak shows until they went out of favour.

Behind his terribly deformed exterior, the man considered to be mentally deficient from birth was a sensitive person.

He hoped to find a woman someday who wouldn’t be repulsed by his looks, and pinned his hopes on meeting a blind woman with whom he could have a relationship.

But his deformities increasingly crippled him, and he spent the last four years of his life in a London hospital. He was 27 when he died.

Room to manoeuvre

Staging an opera in which the Elephant Man sings with a beautiful voice would be ethically wrong, the inventors of The Throat III said in their presentation of the project.

They contend the glove liberates the voice of the opera singer. It gives the tenor more leeway within what is often a hierarchical framework determined by a director and a conductor.

Simple advantage

The glove has only three controls, a continuous one that is controlled by bending the wrist, and two that serve as off and on switches, triggered by the index and middle finger.

The Elephant Man’s deformed hand was the model for the glove, which is one reason why its controls are so rudimentary.

But Unander-Scharin thinks this simplicity is an advantage. Too many sensors and the glove would be a difficult thing to handle.

Voice pitch from the hand

The tenor sings into a microphone and the sound is transmitted to a computer.

The computer runs software called SuperCollider. This is a programmable sound studio that includes a synthesizer and various sound effects. It can certainly change a voice.

The singer controls the sound with hand movements.

“If you bend your hand and move your index finger you can fluctuate between various pre-programmed settings,” says Unander-Scharin.

Wrist and finger

Each programmed setting provides a set of possible ways to change the singer's voice, such as by raising and lowering the pitch, altering it with an ethereal quiver, distorting it or creating a harmonic chorus.

A wiggle of the middle finger makes it shift between various chords which are added to the voice.

A twist of the wrist is comparable to turning the effect knobs of a synthesizer, and transforms the sound continuously. Many of these changes can be made simultaneously in a single motion.

Paper prototypes

It takes time to master The Throat III. Tenor Håkan Starkenberg worked with three researchers in the process.

Prototypes made of paper were evolved to adapt the glove to his hand efficiently.

Unander-Scharin is an opera singer, a composer and a musical technologist. He developed two previous versions of the glove all by himself − The Throat I and II.

Artistic researchers

Kristina Höok and Ludvig Elblaus were also central to the project. They both have solid technological backgrounds and call themselves artistic researchers.

The Swedes define this as technological research conducted from an artistic perspective.

Music made by dance

The Throat III will soon be returning to the stage. In May the performance I Sing the Body Electric! will open first in Sweden and then in South Africa.

Advances have been made on the glove so that it also controls sounds produced by the motion of the elbows and knees.

No orchestra will be needed in the new production. Unander-Scharin explains that the performers will generate sounds and music through the activity of their dancing.

----------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this story at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling