For Icelanders, it pays to be weird

For a century, Iceland tried to be just like other European countries. But suddenly the people in the far North decided to become a bit different.

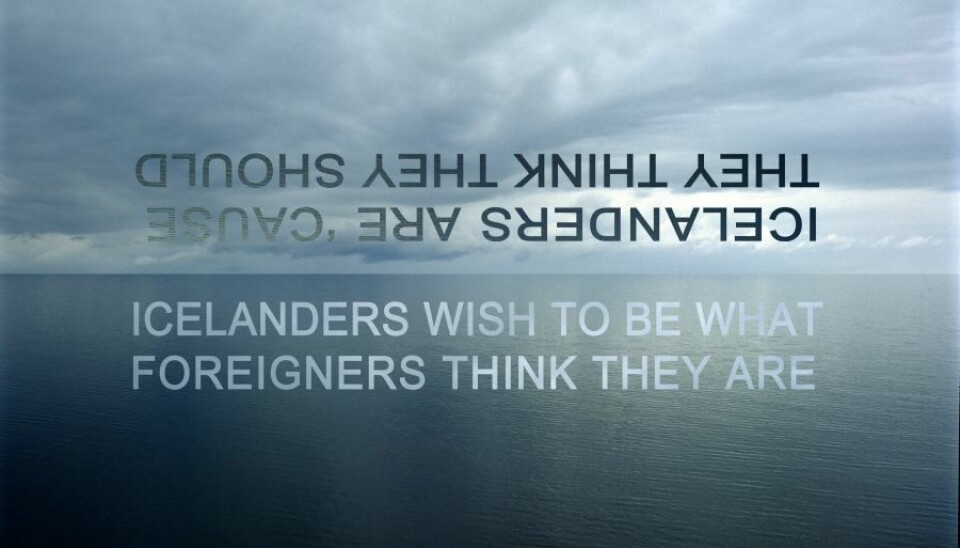

In recent years, Icelanders have started to appear exotic and slightly weird. As recently as twenty years ago, they preferred to be like citizens in any other European country – but there’s money to be made by standing out from the crowd.

This is revealed in a new PhD thesis, which looks into the historic relationship between Icelanders and Danes.

The thesis looks at Icelanders’ self image by analysing art, advertising, stamps and other visual phenomena from the country up in the far North

”The first popular paintings from Iceland were painted by Danes in the 19th century. They depicted wild geysers, waterfalls and volcanoes. In 1930, however, when Icelanders started portraying their country on postcards, the focus shifted to portraying their modern ports and urban culture,” says Ann-Sofie Gremaud, a PhD in visual culture at Copenhagen University.

The first popular paintings from Iceland were painted by Danes in the 19th century. They depicted wild geysers, waterfalls and volcanoes. In 1930, however, when Icelanders started portraying their country on postcards, the focus shifted to portraying their modern ports and urban culture.

Ann-Sofie Gremaud

“But this has now changed. Today, Icelanders wish to be portrayed as eccentric and as close as possible to being indigenous people. There’s a great branding value in this.”

There was not much prestige in being different

This branding strategy seems to have worked: in the past five years, the number of visiting tourists has doubled to 600,000.

This small country has now managed to create an image of itself as an eccentric nation. One in 20 Icelanders claims to have seen fairies, the culture and tourism industries have painted an image of a population in harmony with their wild but beautiful nature – and then there’s the enigmatic singer Björk.

Seeing as this eccentric identity seems to have worked so well as a branding strategy, how come Iceland only recently has started focusing on it? There’s a good explanation for that:

Today, Icelanders wish to be portrayed as eccentric and as close as possible to being indigenous people. There’s a great branding value in this.

Ann-Sofie Gremaud

Back in the days when Iceland was a dependency of the Danish Kingdom, in the period 1662-1944, there wasn’t much prestige associated with being different or indigenous. So even though the Danes regarded the Icelanders as slightly odd, the Icelanders themselves wanted to be regarded as anything but exotic.

Icelanders refused to be exhibited alongside Greenlanders

The difference between the Danish and the Icelandic perception of Iceland becomes very clear if we travel back in time to 1905 – to a ‘colony exhibition’ in the popular Copenhagen amusement park Tivoli.

On display there was what was then regarded as exotic people – people from Greenland, the Faroe Islands, the West Indies (which belonged to Denmark at the time) and Iceland.

But this was unacceptable for the Icelandic student union in Copenhagen:

“They thought it was wrong that they should be likened culturally to West Indians and Greenlanders,” says the researcher.

“Keep in mind that the logic in those days was racist and Europe-centred, and Icelanders insisted that they were on a par with other European countries.”

Beautiful pavilion exhibited exotic crafts

The student’s union sent an official complaint to the organisers, along with a letter to one of the national newspapers, demanding that they shouldn’t be exhibited alongside “the inferior people”.

“They built a big, beautiful pavilion where they could exhibit crafts from Iceland,” she explains.

“In those days, exhibiting old-fashioned crafts wasn’t a priority for the Icelanders. In Denmark, however, it made sense to do so because indigenous peasant culture was all the rage at the time.”

Icelanders: we are a modern fishing nation

But in 1939, when the World Exhibition kicked off in New York, Icelanders got their first opportunity to send an official greeting to the world.

”They decided to hand out free postcards with a photograph of the port of Reykjavik. The photo depicted large villas, steamboats and fishing trawlers,” explains Gremaud.

“On the back side of the postcard there was a description of Reykjavik as a modern capital and the parliamentary centre of Iceland. There were no signs of exotic crafts there.”

Vikings discovered America

The Icelanders selected the motif on their stamps themselves: a portrait of Leif Ericson – the Icelandic Viking who discovered America some 1,000 years ago.

“He was – and still is – and important symbol for Iceland. He travelled, broke boundaries and discovered something new. He was what the Icelandic call a settler (Landnámsmaður)," says the researcher.

Leif Ericson and his vision is one of the few symbols that have survived the last 20 years of identity transformation in Iceland. Today’s Icelanders are just as proud as they those in 1939 that one of their countrymen conquered the world.

“And in the Icelandic branding campaign, the businessmen who recently acquired numerous businesses across the world were referred to as ‘business Vikings’ (útrásarvíkingar). In the branding story, these businessmen travelled from the periphery to Europe, which they conquered using innovation.”

Iceland going in its own direction

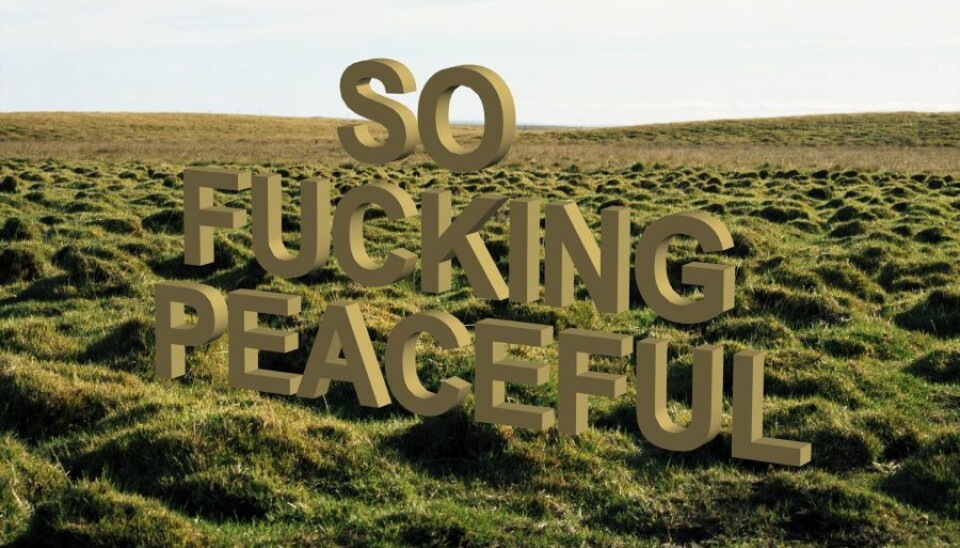

In a world where big cities, with their high-rise buildings, are getting increasingly similar, Iceland is moving in a slightly different direction:

“There’s a branding value in being an indigenous people, formed by uncontrollable forces of nature. Icelanders have given up trying to fight off the traditional image that Europe has associated with them – and it’s paying off,” says Gremaud.

“Iceland has a good tale to tell the world, and European and American tourists are fascinated by the wild, the different and the eccentric.”

--------------------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther