This article was produced and financed by NILU - Norwegian Institute for Air Research

Methane from the Arctic ocean stays put

Methane gas released from the seabed during the summer months leads to an increased methane concentration in the ocean. Surprisingly, very little of the methane gas rising up through the sea appears to reach the atmosphere in the summer.

“Our results are exciting and controversial,” says project leader and senior scientist Cathrine Lund Myhre from NILU – Norwegian Institute for Air Research.

The researchers performed simultaneous measurements close to the seabed, in the ocean and in the atmosphere in the summer of 2014.

“As of today, three independent models employing the marine and atmospheric measurements show that the methane emissions from the seabed in the area did not significantly affect the atmosphere. This is an important message to bring to the debate on the state of the ocean and atmospheric system in the Arctic,” says Myhre.

The researcher says it's important to emphasize that the Arctic has in recent years experienced major changes and average temperatures well above normal values.

“A thorough description of the present state of the Arctic environment and developing adequate measurements, is essential to the detection of future changes of potentially global significance.”

Methane increase since 2006

Levels of methane in the atmosphere have risen by an average of 6 parts per billion (ppb) globally per year since 2006, and slightly more over the Arctic and Norway. Since methane is the most prevalent greenhouse gas after CO2, it is very important to understand why.

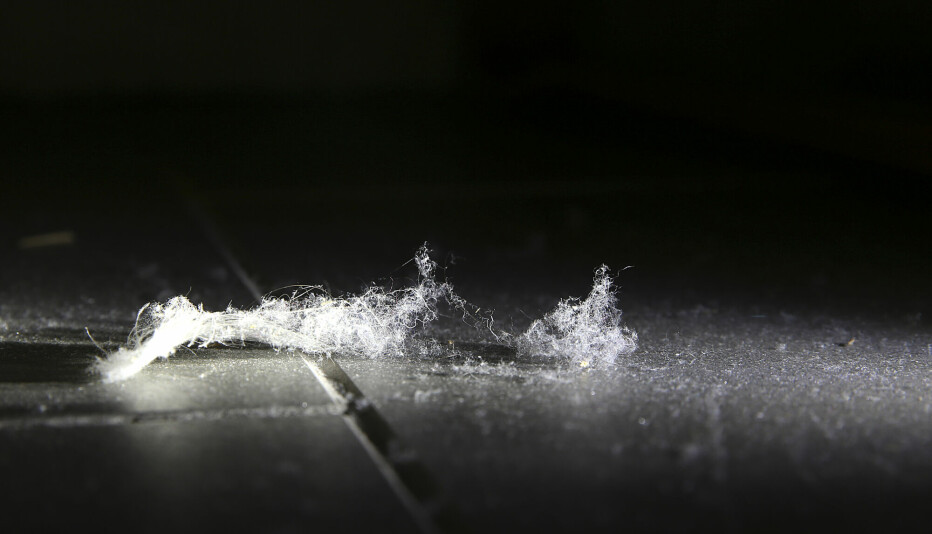

Vast quantities of methane gas are stored under the seabed in ice-like substances called methane hydrates. One possible explanation for the increased methane concentration in the atmosphere is that these hydrates dissolve as the oceans become warmer.

Methane gas leaks from the methane hydrates under the seabed, and rises through the water. The scientists want to find out if these emissions are increasing, and just how much methane is reaching the atmosphere.

“Estimates on how much methane gas is stored beneath the seabed as hydrates vary enormously. A recent calculation suggests that we are talking about 74 000 gigatonnes, and one gigatonne is a billion tonnes,” says professor Jürgen Mienert, director of the Norwegian Centre of Excellence on gas hydrates, environment and climate (CAGE) at the University of Tromsø, Norway.

If any of the methane stored in the Arctic hydrate reservoirs is released into the atmosphere as a result of climate change, this could have a global impact in terms of further climate warming, in addition to what human activities are already contributing.

Why is the methane not released into the atmosphere?

Sea ice, the obvious obstacle to such emissions, is not found here in the summer. So what’s stopping the methane? Emissions from the sea bed are after all clearly visible both on the seabed and in the water column.

"We are talking about 250 active methane seeps found at relatively shallow depths: 90 to 150 meters," says oceanographer Benedicte Ferré from CAGE.

According to her, it is the sea itself that adds obstacles to methane emissions to the atmosphere in the summer. The weather is generally calm during summer, with little wind. This leads to the sea water being divided into sections, whereby layers of different density or salinity form, much like oil over water.

"This means there is no or low exchange of water masses between the surface layer and the layers below. A natural barrier occurs, acting as a ceiling, preventing the methane from reaching the surface." says Ferré.

"But this condition does not last forever: wind blowing over the ocean can mix these layers, causing this natural barrier to disappear. Thus the methane may break the surface and enter the atmosphere," warns Ferré.

She explains that there is still a lot we do not know about seasonal variations. For instance, the methane can also be transported by water masses, or dissolve and be eaten by bacteria in the ocean. Thus long term observations are necessary to understand the emissions throughout the year.

"The only way to obtain these measurements are to use observatories that remain on the seabed for a long time, says Benedicte Ferré. – CAGE set out two such observatories last year, and the data is ready to be retrieved in May."

Unique research collaboration

To determine if methane from these subsea sources actually reach the atmosphere, a unique Norwegian cooperation was established in 2013. Scientists from NILU, CAGE and CICERO made extensive studies of gas emissions from the seabed west of Svalbard in the period June to August 2014, and modelling the fluxes.

"To investigate the methane emissions and their fate, we performed observations on the seabed, in the water column, on the ocean surface, and in the atmosphere from ships, aircraft and land-based stations," says Cathrine Lund Myhre.

Through cooperation with partners from i.a. Cambridge and Manchester University, the scientists got access to one of the world's best-equipped research aircraft. The scientists then used different models to calculate the highest possible methane emissions from the area, and estimate the maximum possible methane release consistent with observations.