The Arctic: we don’t know as much about environmental change in the far north as we'd like to think

The region is warming faster than anywhere else on Earth and its polar bears and melting glaciers have become a key symbols of climate change. But the Arctic, it seems, is not as well researched as you might think.

The first International Polar Year, held over 1882–1883, was an important event for science. The year was the brainchild of Austrian explorer Karl Weyprecht who, after a few years on different research missions, realised that scientists were missing the big picture by not sharing information with each other.

In 1875, at the annual meeting of German Scientists and Physicians in Graz, Austria, he proposed the setting up of an observational network of research stations to monitor the Arctic climate. It was the beginning of collaborative research in the region. Today, data collected 134 years ago on temperature, air pressure, or wind speed is still freely available.

There have been two more International Polar Year events since that inaugural one, most recently in 2007–2008, along with numerous other collaborative expeditions and research missions aimed at understanding aspects of Arctic biology, ecology, climate or geology.

But these co-ordinated efforts are the exception rather than the rule. Instead, most research locations north of the Arctic Circle have developed via a range of particular historical contingencies (easy access by boat or road, for instance, or a stable and open political climate), many of which have had nothing to do with scientific considerations.

Since the Arctic covers some 14.5m square kilometers, and conducting research in remote locations is very expensive, time consuming and often dangerous, the result is an extremely uneven concentration of research effort.

The region is warming faster than anywhere else on Earth and its polar bears and melting glaciers have become a key symbols of climate change. But the Arctic, it seems, is not as well researched as we think it is.

Hard facts

We wanted to put some hard numbers behind this opinion, and to explore what these geographic gaps may mean in terms of broader scientific understanding. That’s what inspired our research project, carried out with colleagues and published earlier in 2018 in Nature Ecology & Evolution. We looked at 1,840 published studies across the Arctic dating back to 1951.

These studies covered nine broad disciplines in the natural and physical sciences and contained 6,246 sampling locations. We also looked at a total of 58,215 citations that refer to the studies. Citations of a particular study signify the amount of times it has been mentioned in other studies and is one indicator of importance within its discipline.

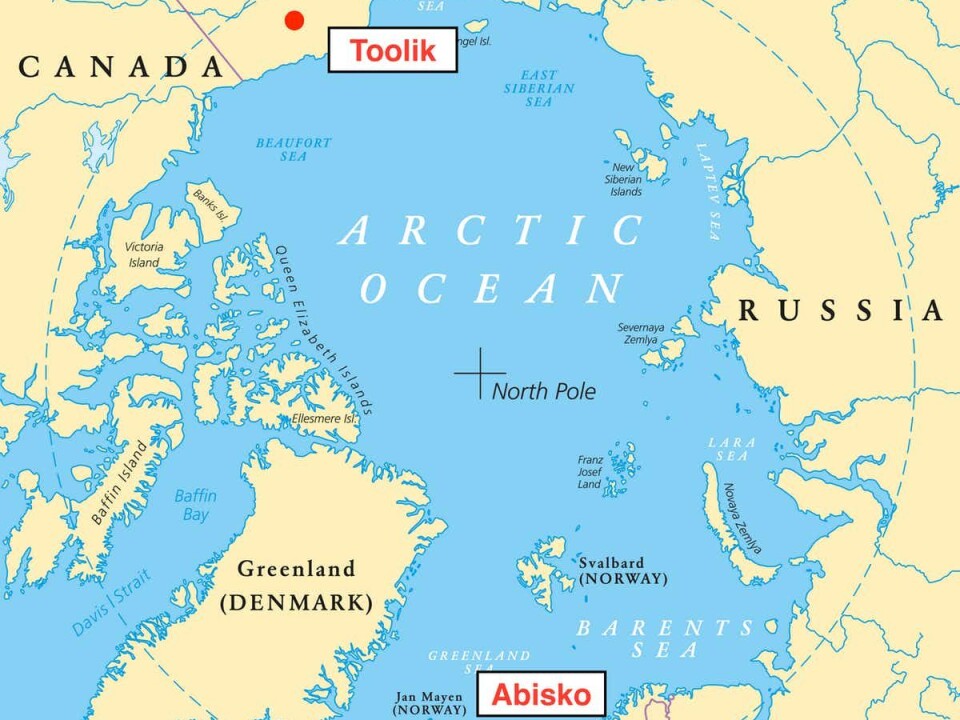

We found that a third of all study citations originate from sites within 50km of two research stations: Toolik Lake in Alaska and Abisko in Sweden. Our results show that for two important variables, temperature and vegetation density, the present pattern of sampling locations in the Arctic represents the average conditions well, but does not represent extreme conditions that are widespread across the region.

The focus on Scandinavia and Alaska means that results from these sites are extended to other locations. The assumption that conditions in two well-studied sites are representative across the Arctic results in the under-sampling of more remote locations. These include vast regions that are relatively colder and warming more rapidly such as Russia’s northern coastline or the thousands of islands that make up Canada’s Arctic Archipelago.

It’s a substantial unknown. Although other parts of Canada and Russia are reasonably well sampled, they too have received considerably less citations, which leads to the poorer dissemination of the knowledge created in these studies. In this way, our understanding of the impact of climate change on the Arctic is biased in favour of sites that are well connected and well resourced.

It is important to note that we are not discounting the wealth of Arctic research conducted in Scandinavia and Alaska. Research at those sites has been, and continues to be, valuable and has enhanced our understanding of Arctic processes within their vicinity. For example, a wetland near Abisko has been studied for three decades during which time there has been an increase in methane emissions as the permafrost (frozen ground) thaws. Similarly, the discovery that the transport of carbon from land to water was much larger in tundra ecosystems than previously thought was uncovered by researchers at Toolik Lake back in the early 1990s.

Regardless of discipline, when looking for scientific evidence, it is habitual to cite research from well known and established locations. One way we could make our understanding of the Arctic more representative is to diversify our research citations by citing research that has been conducted in under-cited or under-sampled locations. Another way is to prioritise research at those under-sampled areas and (try to) convince funding agencies that research in those areas will fill gaps in our knowledge and result in more representative information about the Arctic. We hope our work will aid other scientists in making that point.![]()

---------------

Hakim Abdi, Postdoctoral Researcher, Lund University and Daniel Metcalfe, Senior Lecturer, Department of Physical Geography and Ecosystem Science, Lund University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.