Professor: architects are killing the public space

A Danish professor of urban design criticises architects around the world for planning cities without taking their inhabitants into consideration.

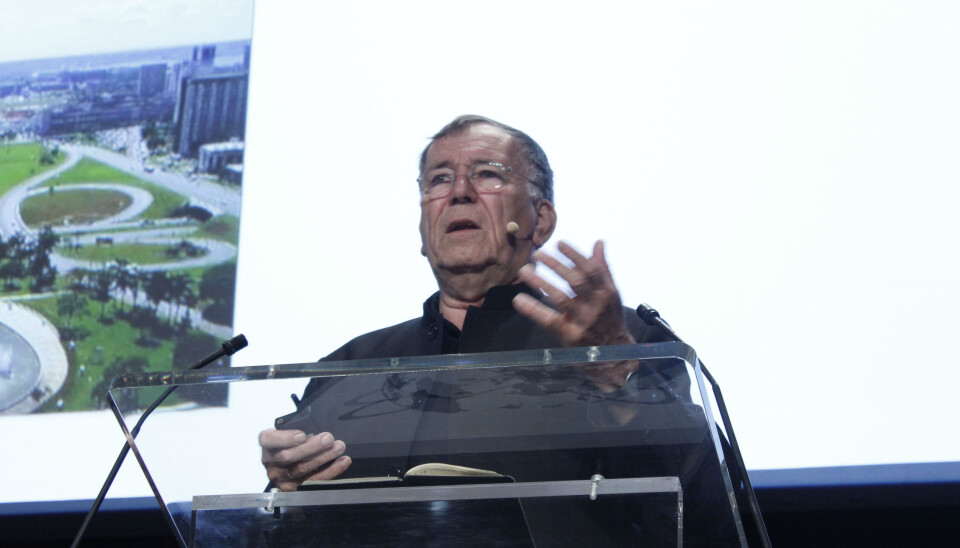

By 2050, 6.3 billion of the world’s population will live in cities, according to a 2011 UN report. And that’s something architects should take seriously when designing and developing cities around the world. But they’re not, says Jan Gehl, a Danish professor of architecture.

Gehl sternly wags his finger at the architects that care more about form than functionality and fail to take the inhabitants into consideration when planning cities. At the same time, Gehl encourages researchers to spend more time studying exactly what makes people are comfortable in their cities.

This has been done in Copenhagen -- a city that is a good example of how architects and researchers can collaborate, he says.

“It’s odd that so little research is being conducted in this field, as architects influence the lives of so many people. We know more about the comfort and preferred habitats of elephants than we know about what makes people thrive in cities,” says Gehl, who is professor emeritus of Urban Design at the School of Architecture at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen.

More space for cars – less space for people

According to Gehl, the cities of the 21st century face some major challenges, and he is not afraid to blame his own profession.

One of the challenges is the lack of space for pedestrians and cyclists. Bike lanes are often used as parking spaces, or to give way to bigger roads and large buildings that are of little or no benefit to the city’s inhabitants.

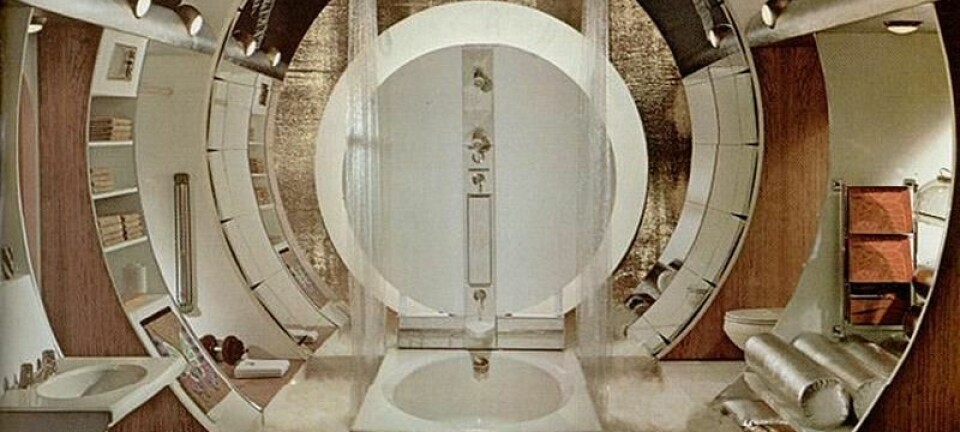

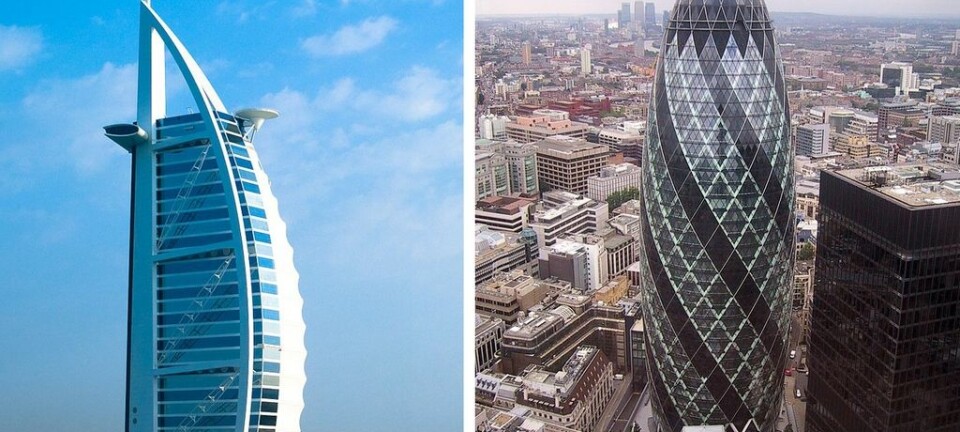

“It seems to me that a lot of architecture is made based on what looks good on the cover of a magazine, but what about functionality for the people that use these buildings and areas? That doesn’t enter into the equation in the same way. We need to give the urban public space to the people that live in the cities,” says Gehl.

He also thinks that decision makers are being fooled a little when the architects present their plans for projects such as a new public square.

“Whenever architects present plans for how a new public square should look, the drawings are riddled with happy people. This is supposed to give the decision makers an idea of how the space will be used. I call it ‘unspecified public life’ because the architects actually have no idea whether people will like the space and use it the way it was intended,” he says.

Artists don’t need researchers

But why do architects and researchers not join forces to find out what works for people?

Gehl, who is himself an architect, explains that it has never been traditional for architects to consider findings from the world of research -- because architecture is art.

“Architects don’t need scientists and researchers. After all, we’re making art. If it looks good, it’s good. We don’t need a researcher to tell us that. However, this means that there is next to no research in our field, so we have hardly an idea whether what we’re making is good or bad,” he says.

Gehl has done research in city spaces alongside his work as an architect and written several books about how the city can be developed to benefit its inhabitants.

Copenhagen is the most liveable city in the world

Even though cities around the world are facing quite a few challenges, some cities are more serious about the needs of their inhabitants than others – Copenhagen being one of them. In 2014 the city was named the most liveable city in the world by the magazine Monocle for the second time in a row.

One of the reasons for this is that Copenhagen Municipality has collaborated with Gehl Architects to carry out a study of how Copenhageners make use their city and then using the results of the study to carry out projects that benefit the city’s inhabitants.

Among other things, the study resulted in wider bike lanes, motivating more people to cycle rather than drive.

“We have to investigate what conditions make people most comfortable in the city. It’s such an important aspect to consider when we’re building cities, “ says Gehl.

He says that Copenhagen’s road to improvement started 52 years ago, when politicians decided that traffic should be banned from the city centre. At the time, cars were congesting the main shopping street. Now the Danish capital has succeeded in driving out cars from the centre. But in other cities car traffic still dominates.

“In many cities people are encouraged not to walk or cycle, because the city hasn’t been planned to make space for cyclists or pedestrians. In those places getting around by car or public transport is easier,” says Gehl.

Less form, more functionality

Since Gehl set out to study how Copenhageners use their city, more metropolitan cities have asked the professor for help.

Moscow, for instance, would like more pedestrians. However, the problem with the Russian capital is that the increasing number of cars filling up the city means that parking spaces are in high demand, which led to parking on the pavement being allowed.

As a result of Gehl’s study, this was later banned, leading to a sudden increase in the number of pedestrians in the city.

In addition to Moscow, Gehl also paid a visit to New York City, suggesting that Times Square and Broadway should be closed for traffic. The mayor of New York City agreed to temporarily turn the vast public spaces into pedestrian areas. The trial period was so successful that both spaces have now been permanently closed for traffic.

Gehl hopes that in future architects and researchers will build and develop cities that benefit its inhabitants.

“As an architect I’m hoping that others will fight to do architecture based on what’s good for people, rather than just focusing on appearance and form,” he says.

--------------

Read the original story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Iben Gøtzsche Thiele