Researchers' Zone:

Researchers have analyzed over 1,000 bog bodies from across Scandinavia. Here's what we found

The Tollund Man, the Grauballe Man and the Huldremose Woman are not the only bog bodies that give us knowledge about the past. We have analyzed and dated over 1.000 bog bodies.

Maybe you have seen them. Behind glass in the museums, their thousand-year-old bodies both terrify and fascinate us.

Bog bodies literally put a face to our ancestors and take us a little closer to the ancient past. It makes us realize how prehistoric and historic times were like our own, and how it was different.

Not only can we see their facial appearance, we also get a glimpse into how people dressed, what they ate and the organic material that surrounded them, material that is not normally preserved.

One might say these individuals have been ‘frozen in time’, providing unique insights into some periods.

Bog bodies have even inspired writers and poets, like Seamus Heaney, who wrote a poem called ‘The Tollund Man’, or the song ‘Now tell us your name’ also about the Tollund Man by singer songwriter Lars Lilholt.

This fascination has meant that, to a large extent, research has focused on sensational finds such as the Grauballe or Tollund men, while less well-preserved human remains have received little attention.

In a new study, we try to address this narrow focus.

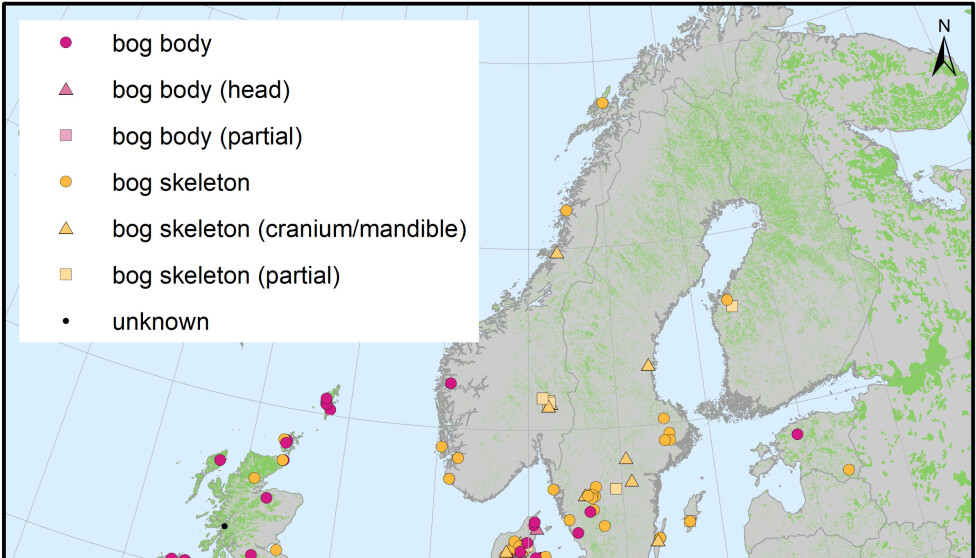

In an effort to understand why and when people ended up in bogs and mires, a new large-scale analysis of all dated human remains from swampy areas across all of Northern Europe has been undertaken.

Mummies and skeletons

In order to fully understand the phenomenon, it is necessary to include all available evidence, including the less well-preserved human remains.

One can separate the bog bodies into the two following categories:

- Bog mummies, comprising almost intact remains such as the Grauballe Man

- Bog skeletons, where only bones are left. The level of preservation of the human remains (bones only, or with the skin and hair intact) mainly depends on the type of bog, as well as weather conditions and the time of year the body was placed in the wetland.

In the new study all scientifically dated human remains from Northern Europe were included.

This means that over 1000 dated human remains were analyzed. More than 130 of the dated individuals were found in Denmark.

This is only a fraction of all the humans that have been found in bogs, as skeletal material found in wetlands cannot be securely dated unless radiocarbon dating is used to place them in time.

Much of this material has not been studied yet. We hope that the new study will increase interest in human remains found in wetlands as a research topic.

90 sites in Denmark

Most of the human remains from Danish bogs were found between 1900 and 1950, when peat digging was still common and the peat was dug by hand.

One can imagine the fright some peat diggers must have experienced when they saw a face or a skull at the end of their shovel!

In Denmark bog mummies are mainly found in parts of Jutland, but bog skeletons have been found in most Danish areas, and are especially concentrated on Zealand.

The new study included over 90 sites from Danish bogs.

Of the 266 Northern European sites in total, we found only one human at the majority of the sites, though there are some with remains from up to four people.

The bloody history of Alken Enge

The Danish site Alken Enge stands out, with its excavated remains of 380 individuals, which makes it one of the biggest ‘collections’ of bog bodies in Northern Europe.

This site bears witness to a violent conflict that took place at the end of the first millennium BC.

The deceased in this conflict were buried together in a wet landscape.

Of the sites with multiple human remains, most reflect a single deposition event.

However, people have returned to some sites on multiple occasions through history, as seen at Bodal Mose on Zealand, where we found two bodies from two different ages: one from the Mesolithic period and one from the Neolithic.

Bogs and bones from six time periods

We have divided alle the bodies and bones into six time periods:

- Phase 1: part of the Danish Mesolithic, 9000 BC to 7000 BC

- Phase 2: covering the period 5200-2800 BC (the part of the Danish Neolithic)

- Phase 3: 2800 to 1600 BC (more or less the Danish Late Neolithic)

- Phase 4: 1600-1000 BC (part of the Danish Bronze Age)

- Phase 5: 1000 BC to AD 1100 (covering arts of Danish Late Bronze Age to the end of the Viking Age)

- Phase 6: AD 1100 to AD 1900 (covering medieval and post-medieval period)

The Koelbherg Male: one the oldboys

The study shows that the earliest evidence of people having been disposed in wetlands occurs in the Mesolithic (9000 – 7000 BC), and that all the known early examples are from Scandinavia.

One example of this is the Koelbjerg Male, in Funen.

The first phase dates between 9000-7000 BC, with only five bodies all from Scandinavia.

Hereafter there is a long expanse of time without any securely dated human remains.

The first sites in the UK and Ireland appear

In the Neolithic (5200 BC - 2800 BC), the tradition is evident again. This is the second time period.

We can see that it continues throughout prehistory and history with some periods with few finds and other times with peaks of activity.

During the Neolithic most finds are in Denmark and southern Sweden, but the earliest examples from Ireland and the UK are also from this phase.

From phase three (2800-1600 BC), most of the dated human remains have been found in south-east England.

Danish examples exist as well, such as a bog skeleton found in Salpetermosen, Hillerød.

The Huldremose woman and her famous underclothing

In the fourth phase (1600-1000 BC) no clear geographical cluster can be seen, but it seems to be a common practice in many regions of Northern Europe.

The fifth phase (1000 BC-AD 1100) is the ‘classical’ bog body phase.

For example, we find the Huldremose woman, recently made famous for her linen underclothing and her skin cape made of hides from a variety of species.

Our study shows that this period is longer than previously thought.

The first dated samples from Poland and the Baltic states occur in this phase, while finds appears to be more common in Denmark, northern Germany and the Irish Midlands than in other areas.

The medieval youngster

The sixth and last phase dates to the period AD 1000-1900, where there are few finds from Scandinavia, but a new cluster emerges in Ireland and UK.

The youngest bog body was found in Ireland at Balykean in 1962.

They found a man buried in a coffin, it was a male who committed suicide in the mid 19th century.

He had not been allowed to be buried in the churchyard and was buried in the bog instead. After he was found in 1962 he was reburied and is not preserved today.

The most recently known Danish bog body was found in Fredriksdal , Kragelund and is from the medieval period.

This bog body was found in 1898, and has not been preserved, although the tunic worn by the man survived and has been dated to around AD 1200.

The violent fate of most bog bodies

Both adult men and women ended up in wetlands, though there are sites, like Alken Enge, where only males have been identified.

The remains in bogs also include children, such as a seven- to eight-year-old child that was placed in Tammosegård Mose during the Neolithic.

The cause of death could only be determined with certainty for 57 individuals, and in 45 cases it involved a violent death.

Violent deaths are found in all phases except for the first one, when we have no evidence for violent death of the five male.

With further radiocarbon dates of bog skeletons we will find out if this pattern holds up.

The earliest evidence of violent death is from Denmark, where a male with an arrowhead embedded in his skull and sternum was uncovered at Porsmose.

Some of the later examples from historic contexts are of people that committed suicide and were buried in the bog instead of a churchyard, or had frozen or drowned in treacherous circumstances.

We have only scratched the surface of their stories

Our study reveals that there has been a long tradition of connecting human remains with bogs.

In Northern Europe we can see that this relationship started in Scandinavia and continues in Denmark into the medieval period, when – according to the dated material - it seems to stop, though the tradition lives on in Ireland and parts of Britain.

We hope that bog bodies will continue to fascinate and inspire further studies.

The database with all published dated material is free for anyone to download and study.

Thanks to modern scientific analyses many secrets of the bog bodies have been revealed, providing a wealth of information about real people throughout history.

May bog bodies continue to help us come face to face with the past.

References:

Sophie Bergerbrant's profile (Academia)