Irish weights were a key Viking Age trading tool

OPINION: Weights played an important role in Viking trading. The weights made it possible to value items and receive the correct payment – and items of huge value were sometimes at stake.

The great streams of silver that reached Scandinavia in the Viking Ages – first the Arabic silver from Russia, and later coins from Germany and Britain – were for the most part converted into silver jewellery by local craftsmen.

Much of the silver arrived as coins, whether through trade, looting or as paid danegeld [a tax raised to pay tribute to the Viking raiders to save a town from being ravaged]. However, in the beginning the central element was the weight of the silver, rather than the coins themselves.

This turned the balance weight scale into an important tool, along with its accompanying weights. Weights were among the most important tools in the Viking Age as they were a prerequisite for many types of trading. The weights made it possible to value items and to get the correct payment for them – the very nerve centre of business. Trading was a highly specialised profession, and items of great value were sometimes at stake.

Decorated shrines and crosses

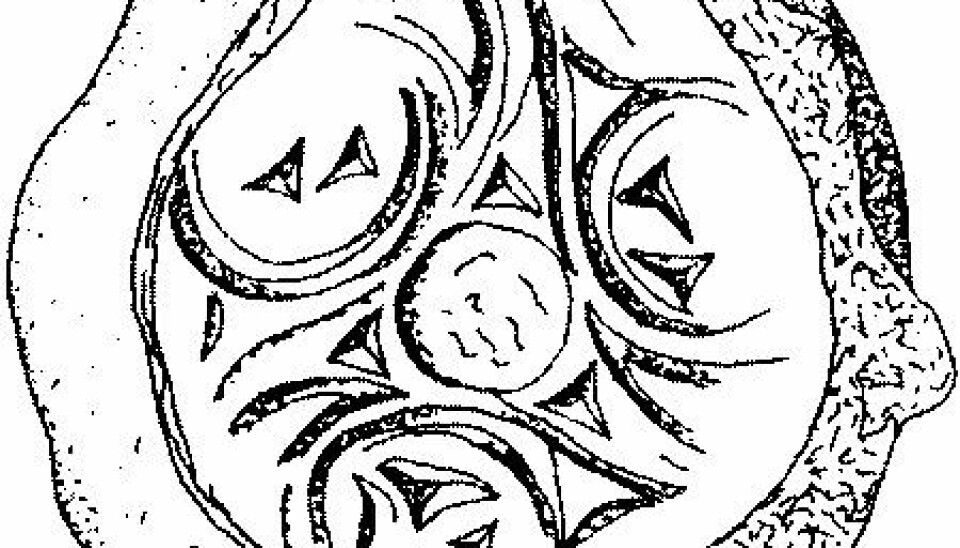

Weights are not uncommon finds from the Viking Age, and from Denmark there are at least six exemplars with their own stories to tell. The weights are made of small Irish decorative mountings that have been broken off the objects they were originally attached to. These objects included shrines, crosses and other furniture from churches and monasteries.

The mountings were later turned into weights by soaking them in lead until they reached the desired weight.

The mountings themselves are made of gilt bronze, and some of them are further decorated with inlaid amber. These weights, which originally formed part of prestigious church objects, ended up in Viking society where their function was somewhat different from their original purpose.

Weights appear in a variety of contexts

Some of the mountings are circular, and that allows us to say with some certainty that they have been attached to reliquaries.

We know of many of these kinds of shrines from churches and monasteries. One can imagine a bunch of marauding Vikings breaking off the decorative mountings so they could bring them back home where they could be turned into jewellery or weights.

The Scandinavians were, however, not the only ones to engage in this form of bad behaviour. Infighting and power struggles in Ireland could also turn the local men into plunderers.

Weights with Irish mountings appear frequently in Scandinavia. In addition to the finds in Denmark, we know of ‘Viking-related’ weights in Norway and from a large burial ground at Kilmainham/IslandBridge near Dublin, Ireland.

Weights tell of international relations

Two of the mountings found in Denmark have different shapes from the other ones. One of them is square and the other is formed as a male mask. These may have been attached to a variety of objects, but cannot be as easily linked to specific church and monastery fixtures as the circular mountings.

These Irish weights with their ’foreign’ mountings therefore indicate lively contact with foreign shores in the Viking Age. This has been known for some time, especially from written sources that tell of the Vikings’ plundering and marauding behaviour towards their neighbours.

The interesting thing is that in recent decades we have seen an increasing number of metal-detector finds that further emphasize these relations. Out of the thousands of finds made every year by volunteers and amateur archaeologists, we occasionally come across rarities like these.

These weights tell us not only about the relations between the Vikings and their neighbours, but also about conflicts, since churches and monasteries were probably not very keen to let go of their valuable treasures.

Merchants needed to be ‘men of the world’

Recasting ’foreign’ decorative mountings into items other than weights is not an unknown phenomenon in Viking Age Scandinavia. We also know of other objects, especially brooches that used to be mountings but which have now been reworked.

This phenomenon is interesting in its own right, because why did people use these ‘recycled mountings’? Was it only because they were thought to be pretty and exotic, or could there perhaps be something more to it?

In international trading relations, there was a potential risk for everyone involved.

The trade could go wrong. One could end up being cheated, getting into trouble or perhaps even getting killed. So when trading with unknown people from distant shores, an additional element of uncertainty was added. There was no guarantee that the people you were trading with shared your worldview and your moral principles.

It was therefore important as a professional merchant to know a lot about many different peoples, so that you could trade successfully with various types of people.

Possessing such an intuitive understanding of different cultures gave the tradesmen a high social status, as this understanding was a prerequisite for much of the trading in the Viking era, which is characterised by extensive contact with the world outside Scandinavia.

Paradoxically, however, the weights with the Irish mountings, which originally ended up in Scandinavia as a result of a conflict, are regarded as a demonstration of the merchant’s extensive understanding of distant places and his ability to enter into trade relations with ‘strangers’.

Weights: important tools and great status symbols

The peculiar weights with the Irish mountings may have had two functions – in addition to their primary function as weights. They could partly signal the merchant’s status: “I am a merchant with some luxury items and access to these kinds of rarities.”

The weights could also signal to foreign people that this was a merchant who could do well outside of his own narrow circle: “I understand foreign cultures and am willing to trade under changing conditions.”

A trade is, in its simplest form, a meeting between two people in which a deal is made and items or services are exchanged. But it is also a meeting where there is an exchange of words and where cultures and opinions meet.

The specific traces only offer clues

It is extremely difficult – more than a thousand years after it took place – to speculate about such meetings. But the specific traces – the objects left behind by the Vikings – can give us a clue about some of the ideas and values that were in play at the time.

The ’Irish weights’ are a good example of this. These weights could add an extra layer of information to the traders – their international design could signal that the merchant was a man of the world, a man who could converse with foreign people, and that for a ’foreigner’ it was safe to trade with him. This merchant was willing to trade with foreign neighbours, who may have had values that were different from his own.

This may also be part of the reason why we sometimes find these very special objects from the Viking Age.

-----------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther